In honour of Grammar Day (4 March), we are joined live by special guest Ellen Jovin, who regularly dispenses grammar advice and wisdom from the Grammar Table. Now she’s testing our grammatical mettle and answering our questions.

Listen to and watch this episode

Video episode

Audio episode

Patreon supporters

Huge thanks to all our great patrons! Your support means a lot to us. Special thanks to:

- Termy

- Matt

- Whitney

- Helen

- Jack

- PharaohKatt

- LordMortis

- Elías

- gramaryen

- Larry

- Rene

- Kristofer

- Andy B

- James

- Nigel

- Meredith

- Kate

- Nasrin

- Joanna

- Nikoli

- Keith

- Ayesha

- Steele

- Margareth

- Manú

- Diego

- Ariaflame

- Rodger

- Rhian

- Colleen

- Ignacio

- Kevin

- Andy from Logophilius

- Stan

- Kathy

- Rach

- Cheyenne

- Felicity

- Amir

- Canny Archer

- O Tim

- Alyssa

- Chris

- aengryballs

- Tadhg

- Luis

- Raina

- Tony

- and WolfDog

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

[PDF] Annala, H. (2008). Changes in subject-verb agreement with collective nouns in British

English from the 18″ Century to the present day (Master’s thesis).

https://tampub.uta.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/79253/gradu02910.pdf

Merriam-Webster says you can end a sentence with a preposition. The internet goes off

(Ellen is quoted herein)

https://www.npr.org/2024/02/27/1233663125/grammar-preposition-sentence-rule-myth-merriam-webster-dictionary

https://bsky.app/profile/arrantpedantry.bsky.social/post/3km2vctifyk2h

Vincent Adultman | BoJack Horseman Wiki

https://bojackhorseman.fandom.com/wiki/Vincent_Adultman

Jonathon Owen: Take My Commas—Please | Arrant Pedantry

https://www.arrantpedantry.com/2012/06/14/take-my-commas-please/

Rachel Nordlinger: The Typology of Reciprocal Constructions

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-022421-064006

Reciprocals and Semantic Typology

https://benjamins.com/catalog/tsl.98

The Grammar of Exchange: A Comparative Study of Reciprocal Constructions Across Languages

https://www.mpi.nl/publications/item551548/grammar-exchange-comparative-study-reciprocal-constructions-across

Reciprocal Constructions and Situation Type

https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/islandora/object/lat%3A1839_1f548a21_b34a_4596_a1db_9d1c5a8464ee

The results

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

DANIEL: Ellen, you tell me that you started trying to stop saying UM and UH when you were teaching?

ELLEN: When I was a TA in graduate school at UCLA in comparative literature, I wanted to sound good. So, I cut my UMs and UHs. I was pretty good at it, actually. I really cut a lot of UMs and UHs. And I got at least two and possibly three — although that just seemed impossible to me — but at least two comments in my evaluations, the student evaluations, at the end of the quarter, they said that I was fine as a teacher, but that I had some weird long pauses when I was teaching.

ELLEN: So, I stopped cutting them after that. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Really?

ELLEN: I don’t think I have that many, so I figured it was creating more trouble than it was worth. And I’m not opposed to them either. So, there you go.

DANIEL: Yeah. I leave in UMs and UHs in the edit, because I think that they’re meaningful, unless it’s distracting, because everything needs to serve the show. If it serves the show and doesn’t detract, then I’ll do it.

ELLEN: Are we going to take a vow of obedience before this begins?

DANIEL: A vow of obedience??

ELLEN: Everything serves the show. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: I didn’t know about this part.

[LAUGHTER]

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

DANIEL: Hello, and welcome to this very special live bonus patron grammar episode of Because Language, a show about linguistics, science of language. My name’s Daniel Midgeley. Let’s meet the team.

We have my friend and podcast pal, Ben Ainslie. Ben, if you were the manager of some kind of table, what kind of table would it be?

BEN: Manage some kind of table. I interpreted that as like at a restaurant? Is that what you mean?

DANIEL: You would commandeer a restaurant table. That’s a very good…

BEN: I believe so.

HEDVIG: Ben, do you remember what our guest does?

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

BEN: Oh, Grammar Table. Right. That makes a lot of sense. Anyway, without brain cells, apparently, it’s very difficult to decipher. I’m still going to go with restaurant table. I would manage restaurant table. I would be like a very charming, but probably quite effete waitperson who’s just like, “All right, people, what are we doing today? Let’s have a good time.”

DANIEL: I like how you’re only commandeering one table, which would make a very easy waiting job.

BEN: Exactly. Yeah, it’d be like a Michelin star restaurant. Like, I’m laser focused on just one group.

DANIEL: Precisely. All right. And we also have my friend and also my podcast pal, Hedvig Skirgård. Hedvig, same question. What kind of table would you commandeer?

HEDVIG: Well, I think that it’s really emotionally draining to sit and have people ask whatever they want of you all the time.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: It sounds like you’d get exhausted. I don’t know if that’s the way Ellen feels or not, but I’ve been in Sweden now for two months and met up with a lot of old friends and had to answer the same questions a bunch of times, “Where do you live now? How long have you been living there? Where in Sweden are you staying right now?” And it’s the same questions about 10 of them that are rotated over like 20 or 40 different people, and it’s driving me nuts. So, I need a table that where it doesn’t drive me nuts.

DANIEL: How about a massage table? That might be more relaxing.

HEDVIG: No, my fingers are not good with that. Oh, something that’s like… Can I just like…? Oh, oh, I know. I’ll talk to people about my techniques for falling asleep.

DANIEL: Oh, very good. Okay.

BEN: You’ll be that person with the table and the little sign that’s just like, “I have kooky sleep habits. Ask me anything.”

DANIEL: Hmm.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: I would choose a coffee table, or perhaps even a dining room table because you have the meal, and then everyone’s still sitting there, and I’ve cleared away the dishes and then you just have really good chats. Some of the best chats come that way.

BEN: You disgustingly wholesome man.

DANIEL: I am. We have a very special guest with us. It’s the author of Rebel with a Clause: Tales and Tips from a Roving Grammarian. She is the proprietor of the Grammar Table from which she dispenses advice, knowledge and wisdom all about all things grammatical. With us for the fourth time, it’s Ellen Jovin. Hey, Ellen.

ELLEN: Thank you. Will I be getting a jacket in honor of this occasion? [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: You’ve been listening. Yes, you do.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

BEN: Little sequined one.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Oh, good. I love sparkly things. This is fantastic.

ELLEN: Like, a rhinestone cowgirl.

DANIEL: Send me your size. For anyone who doesn’t know, tell us about Grammar Table. What’s the mission? Why do you do it? What is it?

ELLEN: I began about five point something years ago to set up on the streets of New York City with a pop-up grammar advice stand. And people just come up to me and ask me language questions. The why is because it seemed like fun.

DANIEL: And is it?

ELLEN: Oh, my gosh, so much fun.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: I never get tired of it.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Sometimes, my life interferes with doing it, and that’s annoying. I love it so much.

DANIEL: Yup. So, are you getting recognised? That’s the question. I don’t know if you’re an institution yet, but I think you might be a fixture. Are people all recognised, “Hey, that lady”?

ELLEN: Well, a lot of my neighbors know me now. I have sat in the same place too much for them to miss me. But I’ve taken this to all 50 states, and the first 47 were pre-COVID, the last 3 were post-COVID. So, there was an interval. A lapse, and I wasn’t going out much and all that kind of stuff. But two of the last three states were Alaska and Hawaii. In Alaska, I was on the side of a mountain on a hiking trail, and two of the people who came by, and they weren’t together knew about the Grammar Table. And then, I was on a beach, an isolated beach. It was Kailua Beach, I believe, in Hawaii. It was my last state. And it was pretty isolated there too. And two women ran up to me and said they had just finished my book.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: But on the other hand, I can go to a school, and no one has any idea of anything. Like, a school with hundreds of people and no one has any clue.

BEN: Nothing more humbling than teenagers.

ELLEN: Wow. I know.

BEN: [LAUGHS] No matter how good you’re feeling that day, they will bring you right back down to earth.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: I’ve discovered that even young university students can be pretty humbling because I’m desperately trying to make them like me, of course.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: And I’m trying with various memes and pop culture references, and they’re just not impressed at all.

DANIEL: I think you found the secret.

HEDVIG: It’s okay. They’re smart.

BEN: I’m fine. It’s fine. Everything’s fine.

HEDVIG: It’s fine.

[LAUGHTER]

ELLEN: I think 8th graders are especially challenging. 8th grade.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: It’s that age.

BEN: That most simian dip of human cognition.

DANIEL: The awkward age. It’s coming up on National Grammar Day in the USA. So, we wanted to invite Ellen Jovin to celebrate with us because grammar is amazing. We want to point out that the language of this episode is English, but we will also entertain questions about the grammars of other languages to the best of our ability. We are joined by many of our great friends and listeners in chat. We want to see who’s here with us. If you want to put where you are in chat and we can read some out, you can make it any level of granularity that you feel comfortable.

ELLEN: [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: All right, we’ve got Diego joining us from LA. We’ve got Robin in Seattle.

ELLEN: That’s my hometown. That’s where I grew up.

DANIEL: Oh, really? We’ve got Nikolai in the Americas. Nikolai, I’m going to accept that level of specificity. Aristemo in Miami.

BEN: [LAUGHS] The entire Western hemisphere.

DANIEL: Dustin says, “On my parents’ couch.” Dustin would say that, of course. That’s a level of specificity that is very specific, but also quite anonymous. Very nice. Lynda in Florida. Steele in Washington, D.C. Anika in Boston. Coco in… Coco’s not in the usual place. Oh, man. Colleen, again, southwest Washington state. We’ve got Portland, we’ve got LA, we’ve got… Ooh, Wendy’s in Basque Country. Very nice. Wow. Okay. Hey, where’s my Perth people? If you’re in Perth, I really want to hear from you. Except for Ben, not you.

BEN: Shut up, Daniel. I am in Perth.

DANIEL: Actually, we’re in Boorloo. We’re on Whadjuk Nyoongar Country. Hey, I wanted to say that. Okay. Once you get to Basque country, what do you do? It sounds really hard to speak.

Well, thank you all for your support, your suggestions, your show ideas, your sociality on Discord. We love doing these live shows with you. That’s just one of the benefits of being a patron. So, if you’re listening to this, not live, think of becoming a patron and watching us live. We have fun. And you’ll be supporting the show and those are good things.

Now, if you’re listening on audio, that is great. You will soak up many linguistic insights that way. But you can also watch this episode on our YouTube account. We are @becauseLangpod. And the advantages are, number one, you can see us, a dubious advantage at this time of the morning.

BEN: [LAUGHS] Such advantage. So great.

DANIEL: Uh-huh. You’ll also be able to see the great, helpful and occasionally hilarious comments that people are making in chat. So, feel free to swap over to our YouTube channel using the link in the podcast description. And if you are watching us in video form, throw us a like, that way the algorithm shows us to more people. All right, are we ready to tackle some grammar questions?

BEN: I have assumed the position, which it would seem is very close to the previous position I had assumed anyway.

DANIEL: Okay. Very good. Now, Ellen, would you like to tell us about your exploits on social media and polling?

ELLEN: Oh, sure. Well, I love doing grammar polls, or it can be grammar adjacent. I’m not particular about hewing only to the domain of grammar. Just anything that’s language-y, I like to post polls on social media sometimes just to see what people think about something that’s total gray area. Sometimes to quiz something that has a more specific correct or incorrect answer. I like posting ones about pronunciation. I use them sometimes to… I usually post out of… I have a fit of curiosity. That’s usually the thing that inspires me to do it. So, I was sitting in the coffee shop this morning, and I posted a coffee shop poll. So, that’s just how it goes.

DANIEL: I think we’re going to see that one too.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Want to know what people think about things. It’s an extension of the table because even though it’s remote, I’m still getting to interact with people.

DANIEL: All right. Well, shall we tackle a few of your recent ones or even ones that maybe aren’t so recent or that haven’t even been seen before, and we’ll see what our listeners judge grammatically. Does that sound all right?

ELLEN: That sounds great.

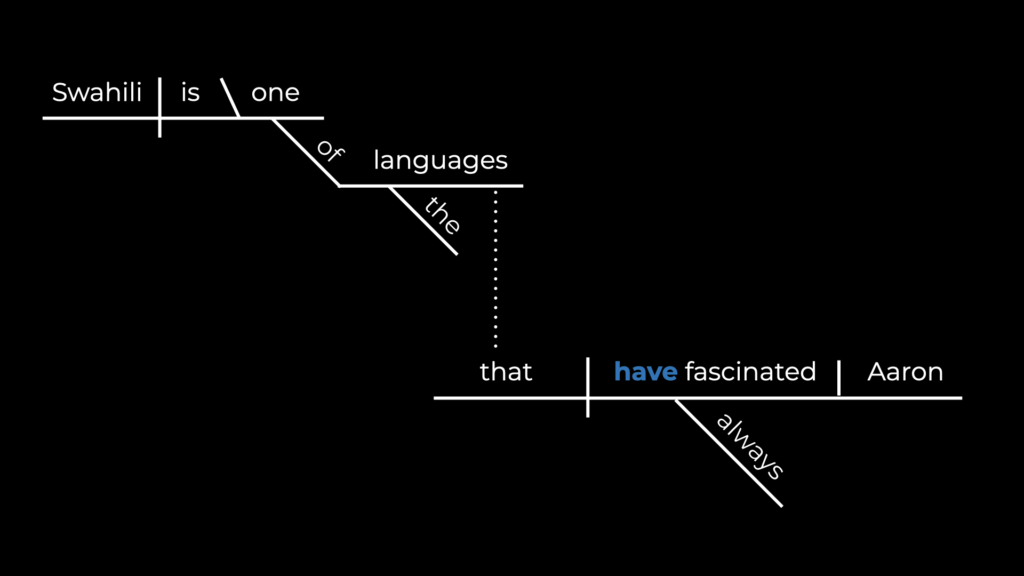

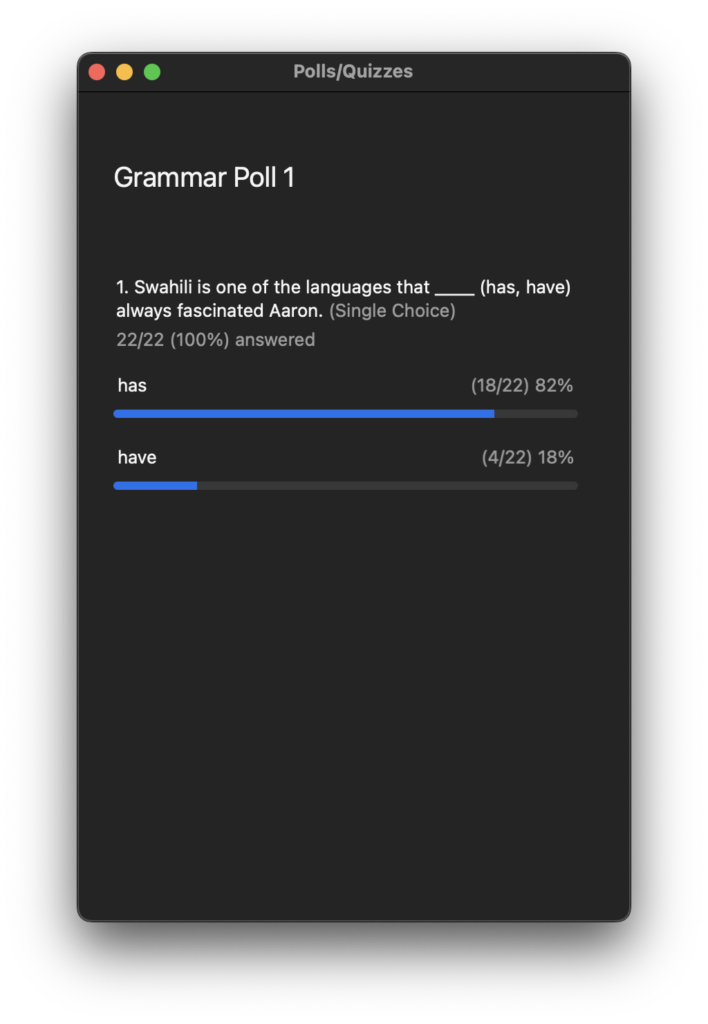

DANIEL: All right. Well, here we go. Here’s number one. It says, “Swahili is one of the languages that has always fascinated Aaron,” or, “that have always fascinated Aaron.” I’m going to be quiet for a second and let you settle that in your mind and vote.

ELLEN: I’m going to sing. No, I’m just kidding. [LAUGHS]

BEN: We definitely need someone to make us, like a Jeopardy ripoff.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Yeah. Think music.

BEN: [IMITATES JEOPARDY THINK MUSIC]

DANIEL: The votes are coming in. 20 people have voted. By the way, Ben, you get two on this one because Ellen’s the cohost, so you have voting rights.

BEN: Yes. I thought you were suggesting that I get two votes for everyone else’s one, and I was like, “Ah, yes, as it should always have been.”

DANIEL: Would you like two votes, Ben?

BEN: [LAUGHS] Absolutely not. It’s like playing mafia or werewolf and being the mayor and getting two votes and then everyone being like, “Well, he’s the kingmaker.”

DANIEL: Hedvig?

HEDVIG: I was just going to say that I’m really interested in this, because I know in theory how this works in English, but I struggle with it. I’ve always blamed that I’m not a native speaker. But when I’ve been here in Sweden, I’ve realised that we conjugate adjectives for number, and apparently, I can’t do that properly, either.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: You’ve got this thing or Skinner thing like, “Uh, am I the problem? No, no, it’s grammar that is at fault.”

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: If you go back through our transcripts, there’s a bit where Hedvig tells us that she actually… you got your Swedish teaching license revoked, because you were no longer Swedish enough.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah. Well, the linguists at Stockholm University have said I’m not allowed to tell foreigners how things work.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: And I think that I’m now teaching at Uppsala University, and I think the Uppsala University crowd is starting to catch on as well. I know linguistics.

DANIEL: The grift. You just got to move to different…

BEN: Just not my mother tongue. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Move to different towns like Joseph Smith and keep the grift going.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: You’ve got a different family in every university.

DANIEL: Let’s check the results for this one. Let’s see what our respondents said. It looks like 82% of our respondents said “has,” that Swahili is one of the languages that has always fascinated Aaron. And only 18% of us said “have.” So, it looks like a lot of us were persuaded by the singular. Ellen, what’s the expected answer? What’s the right prescriptive answer? Because Swahili is one of the languages… I got to say, my year eight teacher, who was a switched-on grammar person, she always said, “Just take out any prepositional phrases when you’re trying to figure out subject-verb agreement.” So, one of the languages she would have said, “You take out of the languages,” that leaves us with one. Does that sound right, Ellen? What’s your advice on this?

ELLEN: Well, I like questions with complications. So, it’s rarely extremely straightforward with any of the questions. I guess occasionally it is. But this is not one of those examples. So, what you just cited, the take out the prepositional phrase thing, that works if you have a simple independent clause, a main clause with, say, a noun or a pronoun followed by a prepositional phrase, and then you’re picking the verb to go with it. But that’s not what we have here. We have Swahili is the subject, then “is” is the verb that corresponds to that, singular subject, singular verb. Good so far?

DANIEL: Oh, okay.

ELLEN: And then you have one. And then, now we’re entering the subject complement terrain. This is Swahili equals one, okay. And then, all of these things are attached to the one. “One of the languages that,” and we have here a relative clause. I don’t know if this is familiar terminology or if you might use different terminology, but that “has or have always fascinated Aaron” is an adjectival clause modifying that. And then, the question is… This is how I would do it, technically, in a prescriptive sense. It’s just not what people think is correct no matter what they’re doing.

BEN: This is what he asked for. He was like…

DANIEL: I wanted to know.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

BEN: Get the rulebook out.

DANIEL: Give me the ruler.

ELLEN: So, a simpler way of explaining this is, Swahili is one of the multiple languages that. Does that make you want to change your answer at all? Anyone, does that make you want to go plural, where you went singular before?

DANIEL: Maybe a little.

ELLEN: That’s the idea here. It’s one of a basket of multiple languages that have always fascinated Aaron.

DANIEL: Right. It’s true.

BEN: Yeah, that kind of intuitively does jibe in my head.

DANIEL: There are a bunch of them.

BEN: Yeah.

ELLEN: “That” that refers back to languages. It doesn’t refer back to Swahili. It doesn’t refer back to one. But you have so many singulars. You have Swahili, singular noun. You have “is,” you have “one.” And it just makes people want a singular verb. So, I do put have here in writing, but I know that a lot of people think it’s wrong. I have mixed feelings about it, because it sounds weird to the ear, because typically in speech through most of my life, I would have just used a singular verb. But it really is one of the multiple languages that have of this bucket that have always fascinated Aaron. So, it’s not the structure that your teacher was talking about.

BEN: According to the rules, this is a dog that quacks and flaps a little bit.

ELLEN: Well, I think the problem with the rules, as they are often taught, is that they are over… I don’t even think the rule, the way it’s taught normally, is so oversimplified. It’s often that later you learn it in a simplified context, and then language is actually much messier and more complicated.

BEN: Right.

ELLEN: Yeah. You study the grammar of relatively simple structures, but you don’t always go that deep. And so, when you really start to look at this, there are multiple things going on. You have the main clause, and then you have a relative dependent clause that modifies the subject complement. Fancy, right?

DANIEL: Yeah.

ELLEN: Most people will not notice if you put “has” and many people notice if you put it haves, so you have to decide philosophically what kind of a conjugator you want to be.

DANIEL: Yeah.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Ellen, can I ask you…?

LYNDA: Ellen, can I ask you a question too?

HEDVIG: Oh, Lynda first.

ELLEN: Go ahead.

LYNDA: What you’re saying is that you’ve got Swahili is one. So, you’ve got your subject, your verb “is” and then you’ve got your subject complement “one.” But then you’ve got of the languages, which is a prepositional phrase. We know that a prepositional phrase itself can be a subject or an object, but that’s not what it’s doing here, because it’s followed by the word “that” which gives you a relative clause.

ELLEN: Right.

LYNDA: So, what you’re saying is that “Swahili” is your relative clause. The relative clause takes place of a complement in this structure. And since Swahili is one, that’s saying Swahili is one singular, that is why your verb should be singular. I know it’s pedantic, but that is the way I learned it.

DANIEL: That is how we roll around here today.

BEN: Yeah. Pedantry. The flavor of the day.

ELLEN: I’m not sure there was a point where I went off the railroad track. So, I didn’t follow that all the way through to the end. But if this sentence were… One of the languages I like… Okay, he’s studying five languages. One of the languages is Swahili. Then, it would follow the rule, Daniel, that you mentioned initially, one is the subject of the language. Well, the whole subject really is one of the languages. But the subject that you would have learned for purposes of verb conjugation, be one of the languages, would be a modifier for that. And then clearly, it would be one is. You don’t do one of the languages are.

But if you diagram this, you have is one. When I say diagram, I’m talking about the old-fashioned diagramming, which some of you may remember from school and some of you won’t, but you would have one. And then under that, you would have of prepositional phrase languages object, below languages. And then, you would have a dotted line that goes down to a new clause, and that would be the subject of that clause. The verb has or have is matched up with that and then always fascinated Aaron. This is a troubling one to start with.

BEN: Yeah. Daniel, come on, man.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: We go hard.

BEN: We go hard.

ELLEN: It’s really my fault. Sorry.

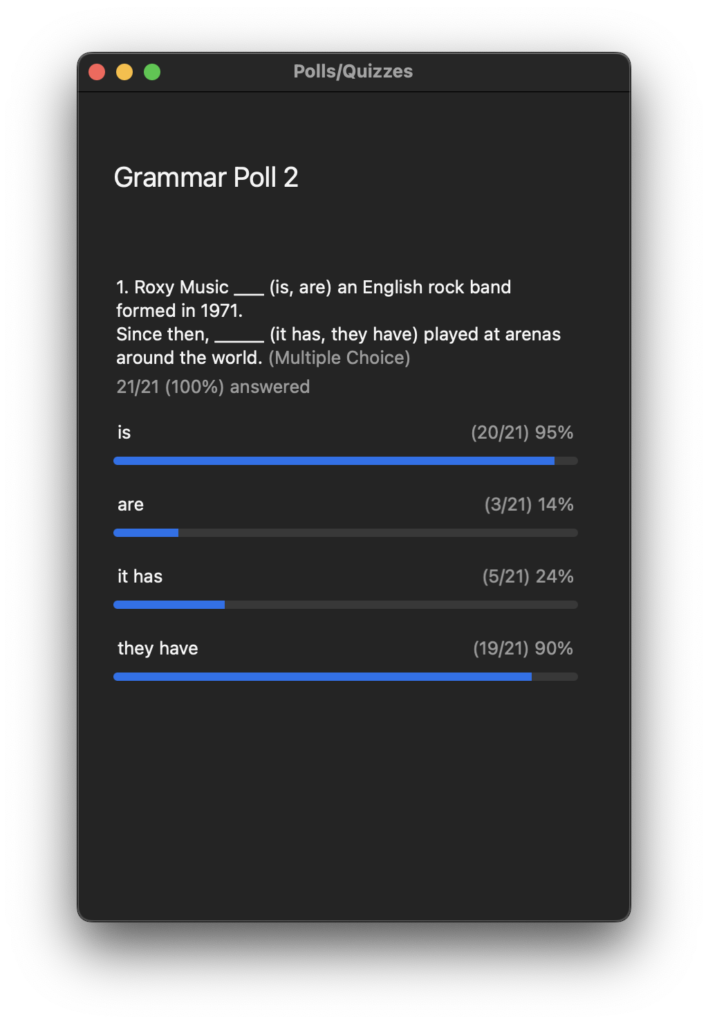

DANIEL: No, it’s cool. I chose these. You gave me a ton. I could have done a lot of different things here. I had choices. Here it is. Second one. Roxy Music is or Roxy Music are an English rock band formed in 1971. Since then, it has played, or since then, they have played at arenas around the world. This is a multiple-choice thing. So, you can choose any of these. You can choose is or are. Don’t choose both. You can choose it has or they have. We’re going to see what happens.

ELLEN: Wait, I don’t think you… I have an objection.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: No, I understand what you’re saying, Ellen. These aren’t mutually exclusive choices. You can choose more than one.

ELLEN: Oh, okay.

DANIEL: Yeah. So, I decided to do it this way so that you can choose is and they have or any combination.

ELLEN: And Daniel, dummy Ben question time. After I’ve submitted it, how do I get it back up, or do you have to put it back up for everyone?

DANIEL: I have to put it back up, but I’m going to leave it here for a while. So, let’s talk through while people are making their choices. I was going to say, when you’re dealing with subject-verb agreement, as we have been, you can go three different ways in the research that I’ve seen. You can go structural, which is what we’ve been talking about. You can kind of go proximal, where the nearest thing kind of leaves a singular or plural impression, as we had in the last one with languages and that colors things a little bit, independent of structure. And then, you can kind of go notional, and that depends on whether you feel like Roxy Music is a singular entity or a plural entity for the purposes of this discussion. So, the results are filtering in. Ellen, while that’s going on, do you have any feelings on this?

ELLEN: I’m still upset about the languages one.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: We’ll come back to it in quite … crosstalk]

BEN: Daniel, we have a fixation.

ELLEN: Before I respond to this, I just want to say that I’m seeing the comments, but I can’t fully attend to what’s happening now in front of me, but I want to acknowledge the pain that I’m seeing in the comments.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Was this for Lynda that I was going to repeat it? The sentence the way I said it, just for that one?

DANIEL: Sure.

ELLEN: I’m just going back. Sorry. Okay.

HEDVIG: Yes.

ELLEN: What was my sentence again? Of the languages that have always fascinated Aaron, Swahili is just one. So, you can hear that that is really conceptually tied more to languages. But I see other comments. Could you argue that it’s tied to one? I think based on a logic basis, if you draw a diagram of it. Not a diagram, like the traditional sentence diagram, but actually draw the languages and then the one language, Swahili in the middle, and then think about what it’s really saying, I think you can’t really make the argument, but I can certainly live with the singular, and I’m not going to chase after you. I just want you all to know that or judge you. I won’t judge you. Okay. Now, Roxy Music…

BEN: Or, just Ellen with a table under her arm being like, “No, I’m not finished.”

ELLEN: [LAUGHS] So now, this topic though, Roxy Music, I love this band. I love the band thing, because every time I go to a Wikipedia British English entry, one that’s written in British English, it’ll have a singular band name and then a plural verb. And if I post it for American English speakers, it completely flips people out.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: It causes trauma. It’s funny because they must see them. They must see them. People google bands all the time, right?

HEDVIG: But also, I wanted to tag on to that, Ellen, if I may, about this thing about grammar as a feeling and variation being okay. Right?

DANIEL: Yeah.

ELLEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: We love this.

HEDVIG: Like, we can deal with a lot of variation. If anything, sometimes when we have a preference, it’s equally valid as our aesthetic preferences. Like, I don’t like lime green. I don’t go around shouting at people wearing lime green sweaters. And if I understand, people…

BEN: Oh, really? You should give it a try. It’s very rewarding.

ELLEN: In college, I had lime green, pointy pumps.

BEN: Pointy pumps.

BEN: All right. Well, I hated that. That sounds…

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Hate your pumps.

HEDVIG: But it’s not… As long as I get it. I just feel like people make a mountain out of a mole hill sometimes. They want to present a really logical, rational system. I’ve studied languages. I know that if something is very frequent, it often behaves irregularly. So, meh.

DANIEL: We often feel like if we can find a reason why something should be so, it therefore must be so. And I don’t think that’s true.

ELLEN: Right. Yup.

HEDVIG: That’s a very good point.

BEN: For this one, I’m going to steal wholesale from the comments. Termy for the previous question said, “This is a duck rabbit for me.” Like, depending on which way I look at it can definitely go both ways, referencing that wonderful image of like, “Is it a duck? Is it a rabbit?” This one is 100% that for me, because bands 100% exist in my head as singular entities. And then, you see a band play and they 100% exist as a group of people doing a thing. Muse is a singular artistic entity whom I love. But there’s three guys who make up muse. [LAUGHS] It’s just that both of those things are 100% true simultaneously.

DANIEL: Yup.

ELLEN: So, are you and is they have…

DANIEL: Yeah. What did you say that?

BEN: That’s exactly what I said, is and they have.

ELLEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] All right, well, let’s see what we got. Dude, I’m going to share the results. Yup. Most of us were is, they have. Check it out.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: How can we account for this? Why would we mentally think of them as one entity and then one sentence later, think of them as a multiple entity? What’s going on? What’s triggering this shift, Ellen?

BEN: [SINGING] Cognitive dissonance. Sorry.

ELLEN: Life is chaos.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: And death is coming for us all.

ELLEN: I see a comment from Liz. My grammar book says, it depends on whether the noun is being considered as a block or as a bunch of individuals doing stuff. That’s generally true. What I find, though, is that it’s very hard for many American English speakers to think of a group as individuals. So, for example, the couple is versus the couple are, or the family is versus the family are, it’s very natural for me to use plural verbs with those. I use both. I’m not particular about it, but for a lot of people, it just sounds wrong here in New York City, where I live. I would do is and they have here. For me, I really can’t say Roxy Music are. That would be really unnatural for me, but I definitely am not going to be… I find an editorial type who’s remembering what they learned in English here might do it has and I can’t do that. There’s no way. That’s not happening.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: Brain says no.

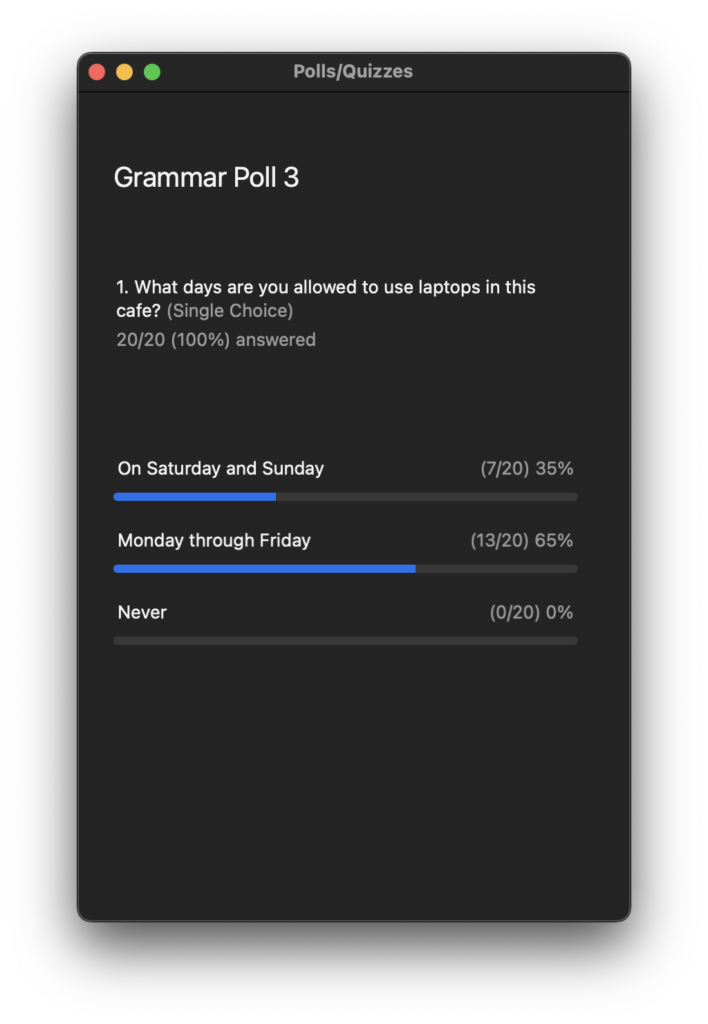

DANIEL: Let’s do our third one here. And I am going to launch number three. I think this is our laptop example. Oh, that’s very tiny. I think I’m going to…

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

BEN: Oh, I can see it.

ELLEN: Can you read it to us?

BEN: And I’m the only person who matters, obviously.

DANIEL: Would you please read it, Ellen?

ELLEN: Cau you read line by line to us?

DANIEL: Oh, yeah, please.

BEN: I’m going to do it for the sake of people who can’t see the image at all. You’ve got a laminated A4 sign, posted on what is presumably like a library door or something like that. Pardon? What’s Daniel mouthing?

DANIEL: Cafe door. Yes.

ELLEN: It was a cafe door. Yeah.

BEN: All right. And there’s a Clip Art picture of a laptop with the big red cancel sign overlaid over the top of it. And below it is the text, “No laptops.” New line. “Saturday and Sunday only.” New line. “Thank you for understanding.” End of words.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: I love this example.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Because this is not about grammar. This is about communication in a pure, condensed sense.

DANIEL: Yeah.

ELLEN: I was pretty excited about this one when I saw it.

HEDVIG: Yeah, this is really fun. I love it.

ELLEN: We got food and drink here too, by the way. It’s a very nice little cafe. But I saw the sign when I was walking in and I thought, “I bet that causes trouble.” [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Trouble. [LAUGHS]

BEN: The thing I wonder about is, I go beyond the language of this, and I go back to when I was a waiter and [LAUGHS] managing hospitality benches and stuff.

DANIEL: Managing one table.

BEN: I feel like I understand what this sign is probably asking, I think. But I’m a bit perplexed that this isn’t like a self-regulating system, because when cafes get busy enough, they’re just horrible places to use laptops anyway, I find.

DANIEL: Then, you have to know when it’s busy.

ELLEN: This place has a sofa. It has a sofa. And the person who ends up on the sofa could really stay on the sofa for a long time.

BEN: Gotcha. Just consuming that non-infinite renewable resource.

ELLEN: This breakdown is really how the poll was going, last I checked on Twitter as well.

DANIEL: You can see the results, but nobody else can, and I can.

ELLEN: Oh, okay!

DANIEL: Yeah. Okay.

ELLEN: I’m not going to say anything yet.

DANIEL: We’re the only two. All right. Well, should we…?

BEN: Hold on. Submitted. There we go. Sorry, I forgot to fill it in.

DANIEL: Not everyone’s done yet. We still got a couple of stragglers, and they’re confused.

BEN: What happened was you see the picture and then you have to scroll down to actually see the options. I was just scrolling like, “Oh, Daniel shared a pretty picture with us. How nice.”

DANIEL: My picture is tiny, but okay. All right. I’m going to close it off. Let’s see what happened. I’m sharing the results.

BEN: By the way, in comments, Steele has said, “I don’t think there’s a correct answer. I think this is a terrible sign.” And I think he is actually the closest to a fundamental truth on this question.

HEDVIG: I love this…

ELLEN: I’m curious whether… are people surprised by the results looking at this? Is this what you expected?

HEDVIG: No. So, should we say on the record what the results are? So, 35% voted for “on Saturday and Sunday”, which is what I did. And 65%…

BEN: Right. Meaning, laptops are banned on Saturday and Sunday.

DANIEL: You’re allowed on Saturday and Sunday.

HEDVIG: Yeah. And 65%…

BEN: Oh, sorry.

HEDVIG: Yeah, you’re allowed on them, Saturday and Sunday. Because I was just using pure contextual knowledge and I figured maybe this is a place that gets less visitors on the weekend, and therefore laptops are allowed.

BEN: My Australian brain really struggles to comprehend this idea that a cafe could possibly be less busy on the weekend. It just doesn’t make any sense to an Australian.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Right. Maybe that was a bad assumption.

ELLEN: I don’t know for sure, but I’m pretty sure that the actual intended meaning is that you are allowed to use your laptops Monday through Friday. But if I thought about it… when I started to think about it, I thought, well, maybe people don’t really bring their laptops in on Saturday and Sunday because they’re having fun and they’re not working. So, maybe this is an issue during the week when people are using it as their home office. So, I’m not 100% sure.

BEN: This is such a bad sign. [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: And also, I just want to comment. Now, we’re entering a moral dimension of the Grammar Table, which is, I really don’t want to make people feel bad by using their examples. This wasn’t meant to make anyone feel bad. It wasn’t meant to say…

BEN: No. No way.

ELLEN: …”Oh, this is the most ridiculous…” It wasn’t like that. It was because I thought it was interesting and kind of amusing, because it did make my brain do some cartwheels and backflips and now my spine hurts. But it’s just interesting. I like real life examples. I love bathroom signs. Bathroom signs are the best for analyzing the grammar. Do you ever do that? Some of them have so much data to work with. It’s like a 10-bullet list of things you can or cannot do in the bathroom stall. So, I find them very entertaining.

BEN: What?

HEDVIG: Yeah. Like, you’re not supposed to sit with your feet on the thing. Yeah.

ELLEN: There are some really detailed ones.

HEDVIG: But I love these kind of science of pelvic spaces, because I also think of them as a bit of a design failure. Like, almost every building I’ve ever worked in has an A4 printed out that says, “You’re not allowed to use the lift in the case of fire.”

BEN: Yes.

HEDVIG: And they’re always handmade by someone who works in that building, and I’m like, “Why isn’t this an engraved sign attached to the elevator?”

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Like, “Why is everyone reinventing the wheel?”

BEN: Why didn’t the elevator just in bas relief from floor to ceiling on the door like, “If fire, no lift.”

ELLEN: Wait, do you mean, is there a question of authority? Did some random passerby just post this to mess with us? [LAUGHS]

BEN: Maybe it’s not a real… It’s not a real rule.

HEDVIG: There is an engraved sign, but it’s too small, usually is the thing.

DANIEL: Yeah. Okay.

HEDVIG: And then, people have made a bigger sign. Sometimes, it’s for information where it’s like, this has been the case in this building for the last 20 years. And the same with toilet things, where I read those things and I’m like, “Oh, this is a failure of design. Why did anyone ever get the idea that blah, blah, blah?”

ELLEN: I didn’t realize that just conversationally, you use A4 to refer to the paper.

BEN: Yeah, big time.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah. Okay. Yeah, sorry. Yes.

DANIEL: It is a wonderful size.

ELLEN: No, it’s okay. It was interesting.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Yes.

ELLEN: I said the same thing, didn’t I? I was like, “Oh, there’s an A4 laminated sheet.”

ELLEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Yeah.

ELLEN: And it’s really not an A4. It’s eight and a half by 11 inches.

BEN: Oh, because it’s American! It’s US Letter.

DANIEL: It’s American letter…

HEDVIG: It’s US Letter.

DANIEL: It’s US Letter, because, argh, Americans. Augh.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: A4 just means papers of roughly that size.

ELLEN: Does it? Doesn’t it have a particular dimension though?

HEDVIG: It does.

BEN: No, it absolutely does. Yeah.

ELLEN: Oh, okay.

BEN: No, Hedvig means in our metric conception of the world.

HEDVIG: But a peanut is not a nut, etc.

DANIEL: One day, I’m going to come over there and sort out this US letter stuff. And on that day, [ELLEN LAUGHS] I will describe it with this: year-year-year-year, month-month, day-day.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: That is what I’m going to do. Now I’m going to go to number four. I am wielding the broom of…

BEN: Hang on. Hang on. Hang on. Hang on. Hang on.

DANIEL: What?

BEN: Have we settled what the actual intent of the sign was? Have we?

DANIEL: Did you ask them?

ELLEN: No, I’ll have to go ask.

BEN: Okay. [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: I sent it an email because I was a little worried they would see it on social media and think that I was trying to be mean. And so, I sent them a nice little note, so they may write me back.

BEN: We need to send a lady in the trenches to go and figure it out.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

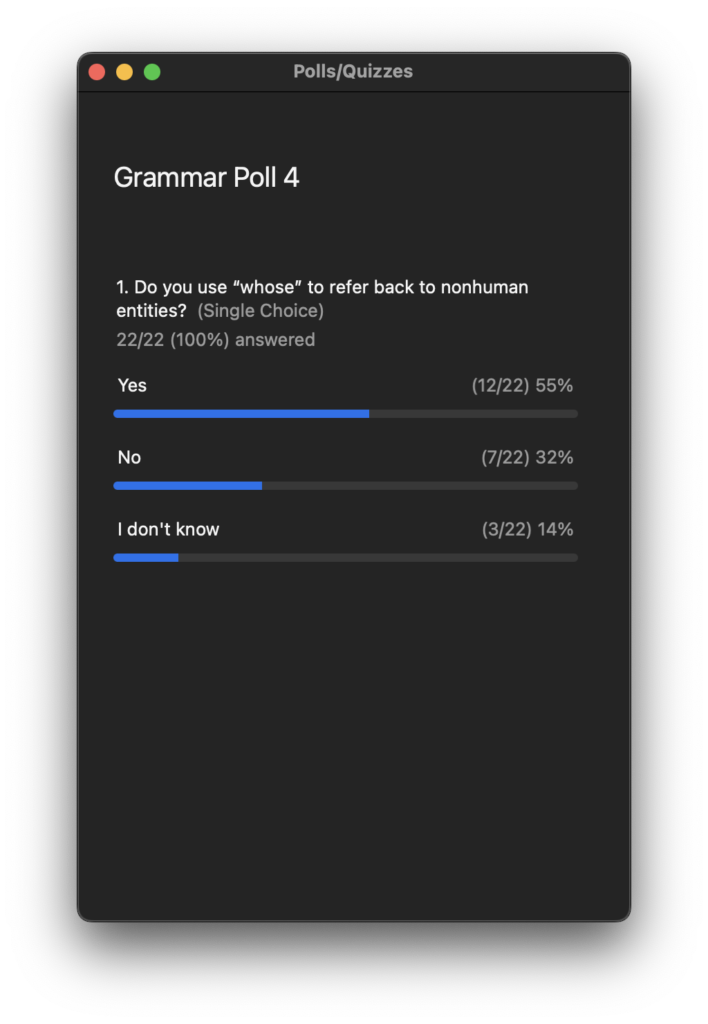

DANIEL: We’re moving on to number four. The question is, do you use whose to refer back to non-human entities.

BEN: Such as?

ELLEN: Like a wall, a book, an idea.

BEN: Okay. I’m trying to think of an example.

DANIEL: The book whose jacket is sitting on the table.

BEN: Oh, yeah.

ELLEN: Yeah. That’s nice. That kind of thing. Thank you.

DANIEL: The bicycle whose owner just left.

HEDVIG: Instead of what.

BEN: Instead of that.

ELLEN: Oh, that’s a great question.

DANIEL: Instead of what.

HEDVIG: Yeah. I need to know what I’m choosing between. Thats?

BEN: Yeah. That’s what I would have thought. The book thats jacket is sitting on the table.

DANIEL: Thats jacket??

ELLEN: Oh, thats.

DANIEL: What?

ELLEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: Its? The book whi… [CONFUSED PHONATION]

BEN: Well, what else…? Daniel, then I agree with Hedvig. If it’s not that, what is the alternative you are proposing?

DANIEL: What is it?? Are we giving away the answer?

ELLEN: Okay. So, this is a little tricky. I’m wishing that I put it in a particular context, but the questions that you’re asking are kind of the whole problem with the idea, as it is taught.

DANIEL: I have had this on the Speakeasy before, and people say, “No” it was Mark, the radio guy, who fancies himself a bit of a stickler. Hi, Mark. And he says, “No, no. Who is for people? And that is for non-human people.” And my answer is, I think I like which. I’m just going to use which for everything.

BEN: Oh, you would you man from the Pacific Northwest.

DANIEL: I would.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Right. This was inspired by the fact that many people, especially in the US, I’m not sure how widespread this is in other English-speaking countries, but many people believe that you have to use who’s for people and whose, the associated forms. That is not for people. And if you use it for people, you’ve just insulted the people. To refer back to the people that I know, that kind of thing, that would be a problem. And then, I’m done. That’s it. This generates anger, because you don’t want to dehumanize people, that kind of thing.

BEN: I’m going to go with whom’s now, the book.

ELLEN: [LAUGHS]

BEN: Whom’s jacket is on the table?

DANIEL: I like it.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Just really throw a grenade in the mix.

DANIEL: We have one strike… What you would say is the book, the jacket of which is on the table.

BEN: Ugh, okay. It’s getting worse and worse as we go along.

DANIEL: That’s terrible.

ELLEN: That was very well done, Daniel. That burns off a lot of calories right there.

DANIEL: I strive for correctness [BEN LAUGHS] no matter how many calorie… even if it makes me burn less calories. Ah, what have I done? Aahhh. Aaaah.

BEN: It does feel sometimes when you’re talking with someone who authentically engages in King’s English or received pronunciation or whatever. I love that Ellen just described it as burning a lot of calories, because sometimes you really do get the impression when they catch themselves in a funky little grammar loop and then they have to go on this circuitous turn in the garden path to get back around to the meaning. It’s like, you could just say the ugly word. It’s fine. We all understand. It’s like, Onst must never engage in… All right, cool. You got us…

DANIEL: So, let’s see. 55% of us admit to using who’s to refer to non-human entities. 32% of us are lying and say no. [ELLEN LAUGHS] And then, 14% of us just don’t know. No, but seriously, there’s just no good way to do it, sometimes, for example. It’s even been semi-lexified, for example, an idea whose time has come. This is an idea whose time has come.

ELLEN: I was just about to say that.

DANIEL: Did I burst your example? I’m sorry.

ELLEN: May I also read an example from Thomas Hardy though?

BEN: Of course.

ELLEN: Okay. I brought this one. One side of the churchyard… This is from The Mayor of Casterbridge. I love Thomas Hardy, so I’ve read all his novels. “One side of the churchyard, the side towards the weather…” And by the way, did you hear that, TOWARDS? People are always beating me up about that. I like my TOWARDS with the S’s.

DANIEL: Nice.

ELLEN: “”…towards the weather was sheltered by ancient thatched mud hall whose eaves overhung as much as one or 2ft. So, the who’s is referring back to the mud wall.”” So, I like this example, because a lot of my questions are designed to undermine common beliefs about grammar that I think get in people’s way. It’s not meant to be a gotcha thing. When I do word questions like this, it’s funny sometimes because… Or, even if I don’t word it this way, people will say, “I never, ever do that.”

And then, Twitter is such a great collection of data and depending what the topic is, you can just search on the phrase and their handle, and you can instantly find that, “Yeah, they did that last week.” I don’t point that out anymore. I did that once. [GIGGLES] Strangely, it didn’t go well! I thought, you know, an injection of reality would be… The person got mad. But anyway, surprisingly, [GIGGLES]…

DANIEL: Exposed.

ELLEN: …I thought the injection of reality was just illuminating. I wasn’t trying to be mean about it. But anyway, everyone does this. It’s a fixture in speech because you can’t avoid it. And I think even in writing, probably pretty much everyone has done it. Some of them are easier to get rid of than the one, the example you started out with, Daniel. But it’s English. It’s the way English is. Who’s is our thing for object references as well?

DANIEL: Are people surprised when they’re expecting a ruler rapping Grammar Tablerian? And they get you and you say things like, “Come on, man, you can make a case for it either way and you don’t get bent out of shape.”

ELLEN: Maybe. I don’t know. I mean, I think I look fairly friendly sitting there. I really don’t look like I’m about to beat people up for using hyphens in a way I disagree with.

BEN: You are not giving off a bunch of cool vibes.

[LAUGHTER]

ELLEN: Yeah. But I do get approached by people who are clearly not going to be dissuaded from any belief they’ve held about language. Yeah, I don’t…

BEN: That must be really frustrating, right? Surely, where you’re just like, “Look, if you’ve come here completely unplastic, what is this interaction about?”

ELLEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: They wanted to talk to someone who also knows how it works, and then they could sit in agreement of how it works, I think.

BEN: [LAUGHS] I see. The Agreement Table with Ellen Jovin. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: It’s not just subject-verb agreement. It’s agreement with me!

ELLEN: [LAUGHS] Yeah. I have a strategy for that. Sometimes, I’ll say something that I think will be accepted, at least a little bit. But I don’t always, because-

BEN: You give them a tidbit.

ELLEN: …not everyone is there. And I can also just be a friendly table. I don’t feel that I’m sacrificing my principles, because it’s not going to make a difference one way or another. Things that really create a lot of heat, like ending with a preposition, that kind of thing, often, you just have to let it go.

HEDVIG: They’re lucky they get you, because I heard someone say that linguists have a tiny language prescriptivist in their head and part of linguistics education is quieting that one down. I think I did linguistics too early and I am too funny in the head. I have the opposite, which is like…

BEN: [LAUGHS] I agree, Hedvig.

HEDVIG: …a little chaos clown that is like, “How can I make this funny? How can poke at people? What can I do to upset them?” And that’s the one that I actually need to keep in check. I feel like Ellen is somewhere in between those two, and that’s probably lucky for her and people should…

ELLEN: So you could have the Naughty Grammar Table.

BEN: Yeah. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Whoa, for naughty grammar.

HEDVIG: I would just be like, “Hey, what if we put all the words you said in a bag, and we pull them out randomly, and we see how much sense it makes?” Maybe it works, you know?

DANIEL: Yeah. Ben has described it this way, and I remember Ben saying this. Some people are like, “I use prescriptive grammar, and that makes me better.” And then, some of us say, “Well, I’m a descriptivist, and that makes me better.”

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: And it’s kind of the same thing.

HEDVIG: I’m not even interested in better or worse. I’m just interested in annoying people.

DANIEL: Okay. That’s right.

BEN: [LAUGHS] By the way, Hedvig, that’s another way of saying worse, you’re worse.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: The other way I’ve described it, I’ve had grammar classes where I’ve taught grammar, but the attendees were approaching the grammar class in the same way that people in a small-town approach the newspaper. Not to find out the facts, but to find out if the reporter got it right.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah.

ELLEN: Oh, that’s interesting. That’s an interesting way to describe it.

DANIEL: Yeah. Now, Heddwyn asks, “My question to Ellen would be, how seriously she takes the results of her Twitter polls? The polls have to be short, which means she cannot differentiate between regional differences, such as British and American English. Are they purely promotional, or does she actually use the results? And if so, how?” What do you get out of these polls, Ellen? What’s in it for you?

ELLEN: I’d have to be a much more organized person than I am to be doing polls in a purely promotional way. People who really interact with me a lot will know that I sometimes post 10 in a row. [GIGGLES] Well, 10 might be exaggerated, but I’ll post 8 in a row because I’m suddenly thinking about a bunch of stuff, and then I won’t be there for three days, and I’ll come back and post one. I have not refined the promotional thing, if that’s what they are. They really are exactly the same idea as the table was in line with a shirt that I have. I have a grammar T-shirt.

Right now, by the way, I’m wearing… You can’t all see it, but I have an “I love grammar T-shirt” on. An “I heart grammar T-shirt” on. But I have one of my favorite ones is “grammar hedonist.” Grammar hedonist. So, I am a pleasure seeker at the Grammar Table. And in my Grammar Table polls, they are for fun. I don’t even remember if I cited any in my book. I don’t think I did, because usually, I will sometimes post them when I’m writing. But it’s more to help me think something through, because I want to know are people thinking the way I am about this, or do they have different feelings, or is there subtopic that I might not think of, especially across different Englishes that they might not have exposure to.

DANIEL: It sounds like what you’re saying is that you just have a curiosity. You just want to find out and you just want to have a discussion.

ELLEN: Yeah. No, I really do want to… That’s the Grammar Table. Before I had the Grammar Table, I was online in language groups all the time talking about language. I belong… I think I still do belong to hundreds of language groups on Facebook, and I just was sitting there talking all the time, so I just moved it outside. So, it didn’t really change that much about my life except make me physically on people’s route to the subway. [LAUGHS]

BEN: I’m interpreting everything Ellen just said as Twitter polls are her cluster of peeled grapes that she holds aloft as she reclines on a divan being like, “[LAUGHS HAUGHTILY] nom.”

ELLEN: I do actually eat so many grapes. So, that’s a great metaphor.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Yeah. Well, and I am aware that Twitter polls are not scientific. So, I don’t use them, because they’re not controlled scientifically. I do think I’m pretty good at constructing polls, because I think through options. There was one thing in there, I think, in the question about British versus American English. They have to be short, so there’s not room. There is a way, depending on the topic, I can often poll… Like, in a secondary poll, I can post about different what English do you speak and get additional information that way. So, I do sometimes have a nested trio maybe to find out more information on that front.

But I also sometimes post polls where I already perfectly well know that both the options that I’ve offered are totally fine. One is used way more in British English. One is used way more in American English. And that’s meant to be more like an educational tool like, “Hey, did you know this was happening on the other side of the Atlantic?”

DANIEL: I have noticed that you are very, very good at finding that one little seesaw point where it’s 50-50 and you add things to the examples where you just know it’s going to take things.

BEN: You know exactly where to put the tip of the crowbar so that…

DANIEL: You know what you’re doing.

BEN: …little bit of pressure just busts it wide open.

DANIEL: You know what you’re doing.

ELLEN: Wow.

DANIEL: aengryballs, do you want to ask your question? Let me know where you are.

AENGRYBALLS: I am here. Yes, I am here.

DANIEL: Yay.

AENGRYBALLS: Yeah. Okay. Very nice. So, I feel like my question is a bit out of sync with the rest of the episode so far because it’s a bit more of a philosophical question.

ELLEN: I’m nonlinear. Don’t even worry about it.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

AENGRYBALLS: Okay. Yeah.

BEN: Non-Euclidean.

AENGRYBALLS: Daniel said it was grammar in a very wide sense. And I suppose we could draw a link with the fact that people are very passionate about grammar rules and following the stuff they learned. So, my question is, essentially, how much do people own the grammar of their idiolect, if you may? Like, if you’re going to do a study or even if you’re going to write a paper, where is the cutoff point between needing to ask for people’s consent when using records of their speech and not needing to ask for their consent?

For example, if you’ve heard someone say something and you wrote it down, do you need to ask for their consent? You obviously do if you’ve recorded their voice. But where is the cutoff point, in your opinion? How much do people own the grammar they use?

ELLEN: Yeah, I actually think these are very interesting questions, not just about grammar, but about writing, the writing process. I’m not a scholar. I have an undergraduate degree in German, and I have a master’s degree in comparative literature. So, I don’t undertake scholarly work. I’m more of a writer type. And I love language learning. Those are my main areas. So, I’ve studied a lot of languages and I’ve had those other things. I teach writing and grammar to adults.

If I had a formal paper in a research context, maybe I’d be following slightly different guidelines, I don’t know. But for me, as a writer, I think about this a lot. And it was a struggle for me when I wrote my book, Rebel with a Clause, about my adventures at the Grammar Table, because I don’t want people to feel bad. I want them to feel comfortable telling me things.

Let me give you an example. If someone sends me an email on Christmas telling me that he’s repulsed by the fact that I discussed the F word in my book, I am probably going to quote him in my next book, but not name him. Not that that happened.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Yeah, I was about to say like, “Ripped from the pages of the real.”

ELLEN: [LAUGHS] So, I get people writing me emails a lot. I’m definitely going to use some of the stuff that I have in there, I’ll use questions or stories that they told me as long as I feel I’m not violating their privacy. This is a human judgment, but also, I change details so that they’re not identifiable. And those things I feel fairly comfortable with people who come to the table, I tell their stories all the time. But again, in the book, when I wrote the book, I said, “I’m moving some locations and changing details,” like I’ll change a two to a three… I speak three languages, I’ll change to two or vice versa.

I live in Michigan. If it’s someone who lives in Michigan and I feel like, I don’t know, the story is so idiosyncratic that maybe his neighbors will recognize him. I might relocate him and change other details. So, I’m quite protective of people. I think I’m more protective than the average writer. It actually is a little bit limiting. It’s something that I struggle with all the time, because to write, you have to tell truth, you know? But I also don’t want people to feel bad.

DANIEL: Yeah.

ELLEN: I like that question a lot. So, for me, that is very relevant, because these are about human tale for me. People share personal human tales. I have to treat those with respect. So, that matters to me very much. And thank you for that question.

DANIEL: Yeah. All right.

HEDVIG: Can I add something?

DANIEL: Please.

HEDVIG: This was sort of related to a discussion that was had on Tumblr for ages ago, which was…

BEN: [LAUGHS] Blow the dust off that reference.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Well, there was a Tumblr where people were posting. Sort of fun, quirky examples from language corpora that linguists have written about in their grammars. Because linguists like to use natural language, so we like to record people, and then just write about what we find in those natural recordings. But people were feeling that… And sometimes if you record a lot of people, they’re going to say some funny stuff, right? They’re going to say their kid did a funny thing or something funny happened, or they say something that’s nonsensical or something. Sometimes that illustrates an interesting grammatical phenomenon. So, the linguist puts it in their grammar, and then people look at this and they say, “This speaker is like talking nonsensical.” It feels like making fun of the speakers. But also, if you recorded me all day, which, ironically, we do record me a lot when I do say funny things.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: It’s quite natural. But in that case, people make fun of maybe individual speakers, but they do… Linguists try to have informed consent. But it’s hard to know where those limits are, because we’re also just so interested in the things people produce. Yeah, it’s not always easy.

ELLEN: I see this in medical kinds of contexts too. I think there are quite a few professionals who are not careful enough with the data that comes to them. You see it if you ride in an elevator in a medical building here, you hear medical professionals talking about things they shouldn’t be talking about, or receptionists answering phones in medical offices, and you can hear the person’s personal data being talked about or it’s on speaker. Crazy stuff like that. So, I really try to be careful.

I do think in principle, in principle, what people post on social media publicly for us all to see, if someone tweets something, I feel like that’s public domain. On the other hand, I still temper that by thinking about how I’m using it. If I’m using it as this person is… I just gave you an example of someone who emailed me on Christmas. I thought it wasn’t a very kind email. I didn’t like the email.

HEDVIG: Mm-hmm.

ELLEN: Since Twitter is searchable, it’s not like a database where it’s all pooled anonymously. Someone can just go search something I write about and find that person and harass them, I wouldn’t feel comfortable with that either. So, there are lots of competing things. A lot of it is logic. Like, what, as a human being, would I find tolerable and fair?

DANIEL: Let’s move it to our favorite game, Related or Not.

BEN: I’m not going to sing this time.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: Look at me growing like a human being.

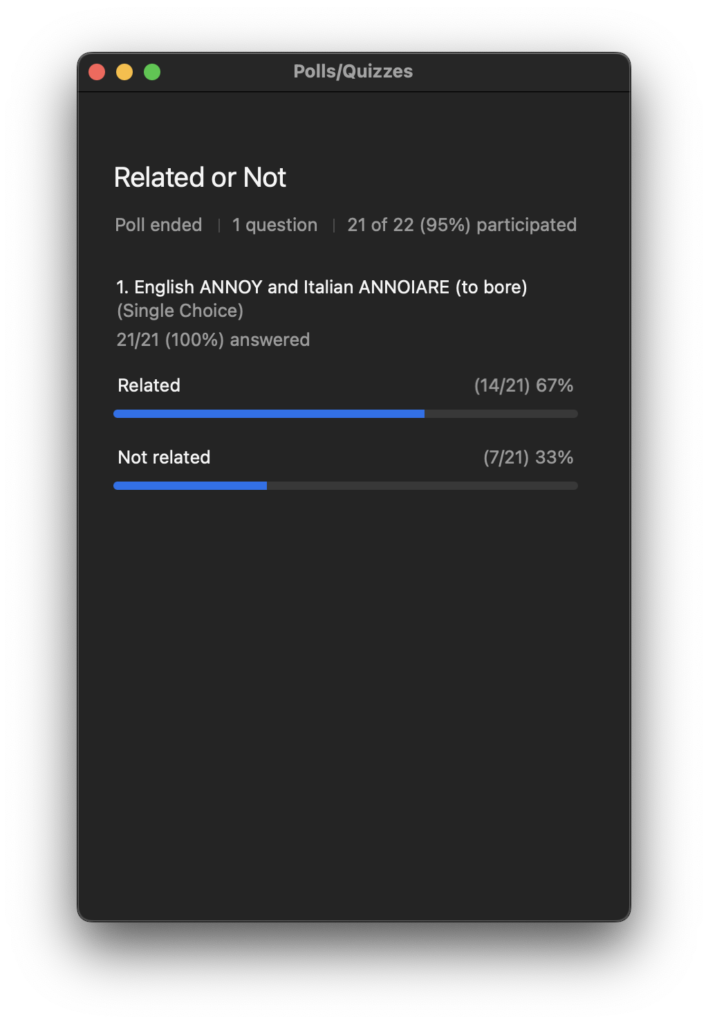

DANIEL: Nobody has sent us a theme yet, but I just put out the call. So, if you are a musician and you want to donate a track to us, just a five-second thing, why not? Let’s see what happens. Hey, Diego, I pulled one of yours, and it was ANNOY. Do you want to come on and do it or do you want me to do it?

DIEGO: Yeah, sure. Sorry, which one?

DANIEL: ANNOY. And then, a similar word in Italian. Do you remember that one?

DIEGO: Right. Yes. ANNOIARE.

DANIEL: That’s the one. How did you come across this? Are you a speaker of Italian?

DIEGO: Not natively, but it’s one of the languages that I’ve studied, and I have family in Italy. So, I’m conversational, I guess we could say.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, I’m launching it. Here we go. We’ve got English ANNOY, to annoy someone, and Italian ANNOIARE, which means to bore, to bore someone. They look pretty similar. People are voting. What do you reckon? Anybody? Let’s have comments from the five of us or the four of us.

BEN: I immediately went, not, because it feels too good, feels too easy. The cynic in me is just like, “Mm, the beautiful woman has walked into the bar and just immediately taken an interest in me? Well, something is amiss. Something is awry here.”

DANIEL: Diego wouldn’t do you that way.

BEN: I don’t know about that. He’s got that beautiful, disarming, outlandish good-look smile.

DANIEL: I know. Okay. Ellen, what’s your instinct?

ELLEN: I remember from my Italian studies that this struck me, and I have no idea. I’m going to just…

[LAUGHTER]

ELLEN: …go with not related, just because.

DANIEL: Okay. Hedvig? Because.

HEDVIG: I went with related, because I think that it’s through French, and that kind of spelling in English reads French loan, and French and Italian are related.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: More closely than either of them are to English.

DANIEL: Well, I bet it’s a false friend, and I bet it’s related to ENNUI, because I know that French has S’ENNUYER, but it’s a trap. So, I said not related, after all, they mean different things. Okay. It looks like many of us have voted. I am going to show the results. What we said was, hmm…

BEN: Two-thirds, one-third.

DANIEL: Two-thirds of us said related. One third of us said not related. Diego, what are the beans? Ready to spill them?

DIEGO: Yes. So, they are related.

BEN: Oh, no.

DIEGO: Through Latin.

HEDVIG: There you go.

DIEGO: Yeah. So, they both go back to a phrase in Latin meaning “be hateful to me.” It’s something that somebody would find hateful. So, in English, it came to mean somebody who’s bothering you. But in Italian, it actually means to bore somebody.

DANIEL: Mm.

ELLEN: That’s also bothersome.

BEN: Yes, very much so.

DIEGO: Absolutely. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yup. That’s what I’ve got. In Latin, there was a word ODIUM, to hate, and you’ll recognise it because it comes to us in ODIOUS, hateful. But it also worked its way into late Latin, INODIARE, and you can see how that sounds like ANNOY, but also ENNUI. From there, Latin INODIARE went different ways. It went to ENOJAR in Spanish, which means to make someone mad. French, ENNUYER to bore, and Italian ANNOIARE to bore, and then to ANNOY in English.

BEN: So, it’s actually a little bit of a… Does it strike anyone else as quite strange that it morphed in a really similar way in both English and Italian, but it morphed in a very different way in French? Like, Hedvig was saying, I would have expected that French and Italian probably would have morphed in a more similar way than English and French did. Yeah, it’s odd that as both languages are like A-N-N-O-Y seems like the way we want to do this, [CHUCKLES] and everyone else is like, “That’s weird. Don’t do that.”

AENGRYBALLS: Actually, in French, it means both.

BEN: Ah, okay.

DANIEL: All right. I like how Spanish: FASTIDIAR. If somebody’s FASTIDIOUS in English, that means they’re fussy. But if something is FASTIDIOSO, it’s like, “Oh, eso me fastidia!” So, there’s a lot of stuff like that. Hey, Diego, thank you so much for that and for all of the stuff you bring. You are a legend.

BEN: Oh, he’s so lovely. I just love Diego. He’s great.

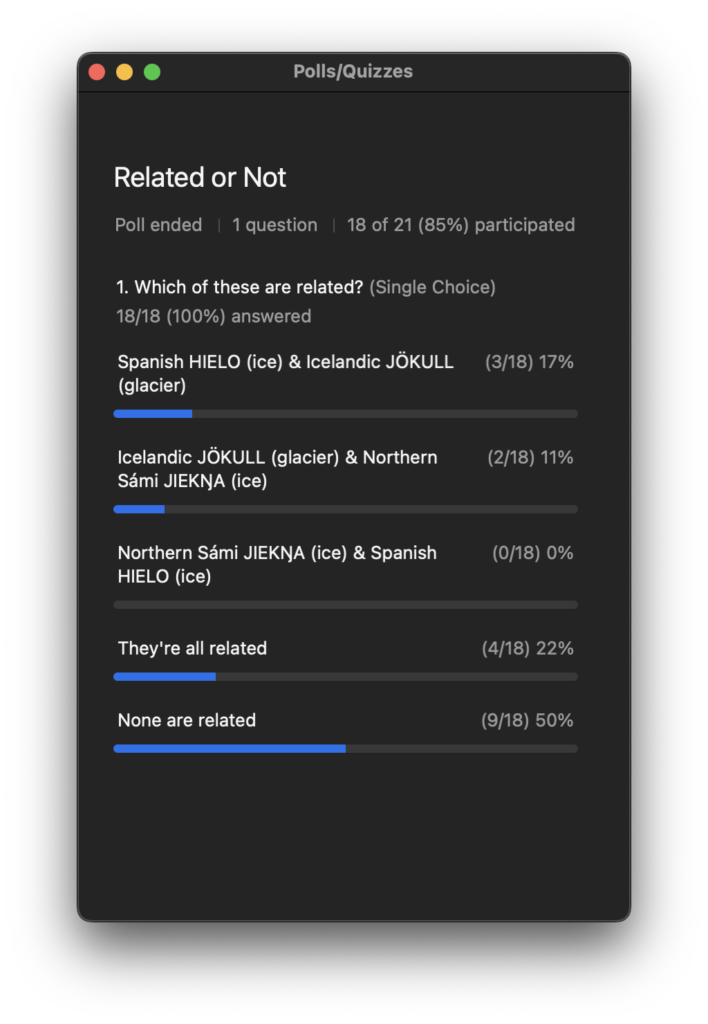

DANIEL: I know. Okay. I have one more. I think we’ll get time for one more. And this one, let’s go with… One from aengryballs. And this one is about ice. Aengry, you want to take it?

BEN: No, he is definitely here. We know this.

DANIEL: We know he’s here.

AENGRYBALLS: I am here, but I don’t have it in front of me. So, I’m afraid I can’t repeat it from memory.

DANIEL: Okay, that’s cool.

BEN: Daniel, your time to shine.

DANIEL: I’ve got it. This is my time. Okay. So, we’ve got three different words. Here we go. Now, there are words for icy things. One is in Spanish. It’s HIELO. Hielo. And that means ice. There’s Icelandic JÖKULL. Oh, hang on. Hedvig, as the Icelandic adjacent person. Jökull.

AENGRYBALLS: Actually, I can pronounce it.

HEDVIG: I love that.

AENGRYBALLS: Actually, I studied Icelandic [CHUCKLES] in university.

BEN: As one does on a whim.

AENGRYBALLS: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Go, go, go.

AENGRYBALLS: I did Nordic studies. But I have to pull up… Okay, so hielo, as I said, Icelandic JÖKULL. Option number two, Icelandic JÖKULL and Northern Sámi JIEKŊA.

DANIEL: JIEKŊA. Okay.

AENGRYBALLS: And third option, Northern Sámi, JIEKŊA and Spanish HIELO. And then, they’re all related, and not related.

BEN: Ooh, tricky.

DANIEL: They’re all icy, and I’m way out of my comfort zone. Hedvig, Ben?

BEN: So…

HEDVIG: That’s a hard one. Well done.

BEN: [LAUGHS] I’m going to go with, these are all related. I’m going to stick my flag in the ice, as it were.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: And I’m going to say these are all related. I’m going to say that because I’ve been reading The Clan of the Cave Bear, and I’m like, “Surely, the Proto-Indo-European word for ice, when everything in Europe was super-duper icy was just fairly consistent.” And so, it’s filtered down into a bunch of Proto-European sort of like HEIR languages, like H-E-I-R.

DANIEL: Okay. All right. Let’s take it to Ellen.

ELLEN: No idea, so I’m going to vote again with no idea. I’m going to vote that Icelandic and northern Sámi are the related ones.

DANIEL: That’s what I said too.

BEN: Yeah. That makes sense, doesn’t it.

DANIEL: I thought Spanish was an accidental similarity, and I thought that maybe the Sámi was a borrowing, which would count as related, not genetically, but through borrowing. That was my answer. Hedvig, what do you think?

HEDVIG: I think that none of them are related.

BEN: Ooh, bold. Love that.

DANIEL: Well…

HEDVIG: It’s just a gut feeling.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Iceland is like, they do have EAS for ice, which might be cognate with the Spanish one, I don’t know. Iceland was settled three times by Norwegian, Danish-ish people. I don’t think there would have been Sámi loans. Yeah. None.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, aengryballs… Oh, I’m going to finish up this poll. Looks like a few people really aren’t sure about this one. We seem to lose our instincts here. I’m going to share the results. What we thought was that most of us thought none of them are related.

BEN: Boo.

DANIEL: But a few people thought that Spanish and Icelandic had a cognate there. All right, aengryballs, hit us with the facts.

AENGRYBALLS: [LAUGHS] I don’t remember. It was a long time ago. I don’t remember.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: What a great troll. That is wonderful.

DANIEL: Well, it turns out I did the best research I could on this. This is why I was saying to myself last night, “I’m doing a lot of research for a show where I’m asking other people questions.” But it’s good. The answer is, as far as I can tell, none of them are related. So, if you said none, you are correct. Spanish HIELO comes back to Proto-Indo-European *gel which is why we have things like CONGEAL and things like that. But Icelandic JÖKULL… How does that double L sound?

AENGRYBALLS: It’s like a /ɬ/. Like, you know, in some South American languages.

HEDVIG: It’s like Nahuatl.

DANIEL: Ah, /ɬ/. It took a different course. It went back to Proto-Germanic, *jekulaz, and I couldn’t take it back any farther than that. Northern Sámi comes from a totally different language family from Proto-Finno-Ugric, *jäŋe. So, as far as I can tell, and please let me know if you are a comparative scholar, none of these are related. Wow.

BEN: I think the real crime here is that Hedvig is two and Ben is zero, and that’s just intolerable.

DANIEL: Not supposed to happen. Not supposed to happen.

BEN: I don’t care for that at all.

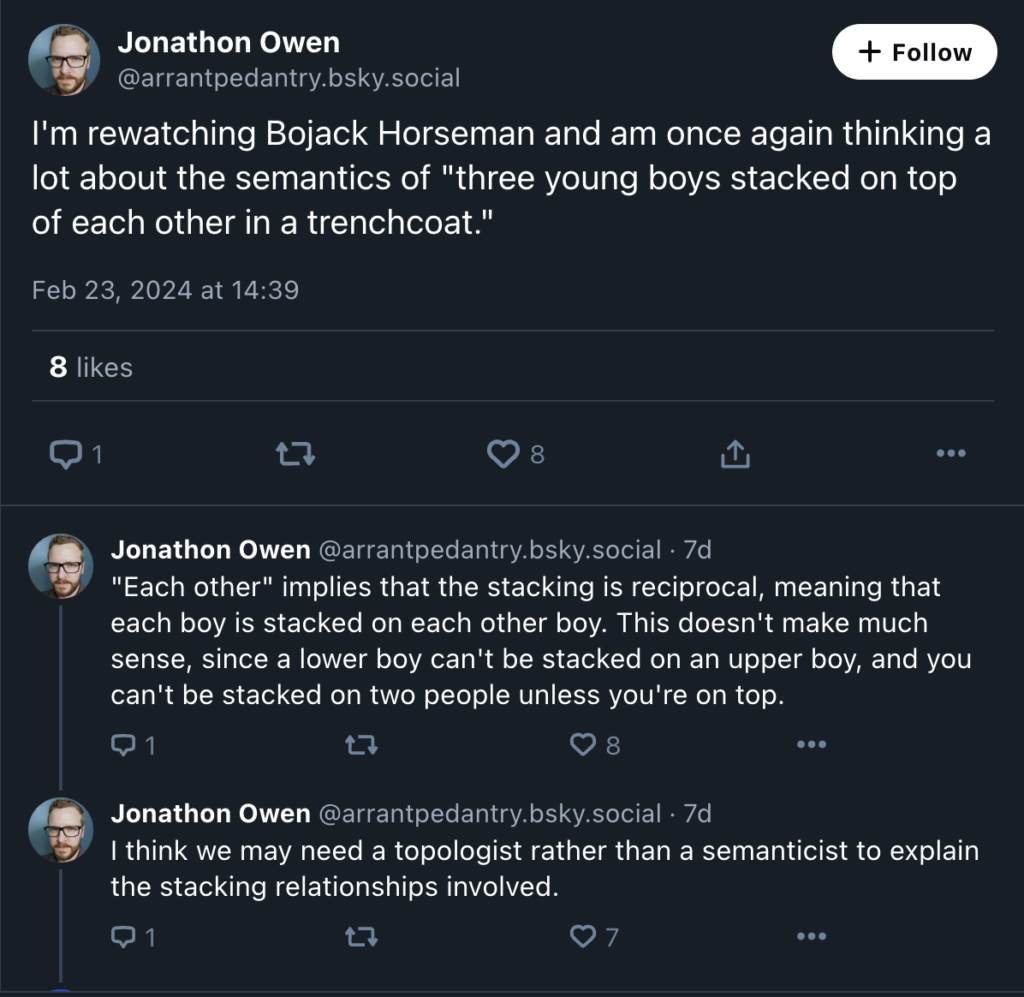

DANIEL: Let’s see. I am going to take it to some more questions. These were floated by our friends in Discord. Now, this one was inspired by Jonathon on Bluesky. See, now, I saw Jonathon Owens skeet on Bluesky. And even though it’s public, I said, “Hey, is it cool if I use this?” And here’s a link. Jonathon, are you, by the way, in attendance? Because if you are, I’ll peg you. I’ll pin you.

ELLEN: I don’t think he is.

DANIEL: He isn’t. Okay. Darn.

BEN: Don’t peg people, Daniel. Well, you can, but [ELLEN LAUGHS], but actually don’t peg them in this context.

DANIEL: I knew it as soon as I said it! But then pinning people wasn’t… Anyway.

BEN: Of the two, I think there is a less bad choice.

DANIEL: It’s all what you’re into. So, Jonathon skeets… Any sentence where SKEET appears is already just suspect. “I’m rewatching BoJack Horseman, and am once again thinking a lot about the semantics of three young boys stacked on top of each other in a trench coat.” We are, of course, talking about…

BEN: Like the classic trope of kids trying to get into somewhere?

DANIEL: Have you not watched BoJack, Ben?

BEN: Not recently enough to remember three people stacked on top of each other.

DANIEL: Oh, okay. Well, we are, of course, talking about one of the characters, Vincent Adultman, who was Princess Carolyn’s boyfriend in Season 1 and Season 2. The BoJack wiki describes Vincent as “three kids stacked up on each other”.

BEN: Okay. Gotcha.

DANIEL: Jonathon continues. And wasn’t there a joke? BoJack says, “Your boyfriend is obviously three boys stacked on top of each other.” And she says, “Oh, you always hate my boyfriends.”

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Jonathon continues, “Each other implies that the stacking is reciprocal. Meaning, that each boy is stacked on each other boy. This doesn’t make much sense since a lower…

BEN: Oh, god. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] “A lower boy can’t be stacked on an upper boy…” I forgot to unpin. I pinned aengryballs, but then I forgot to unpin him. It’s very important to unpin someone after you’ve pinned them. “This doesn’t make much sense, since a lower boy can’t be stacked on an upper boy, and you can’t be stacked on two people unless you’re on top.” Let’s just meditate on that for a while.

BEN: Yes. Wow, we’re getting real deep now.

DANIEL: It would it be quite wrong to say that Vincent’s Adultman is three boys stacked on top of each other. Should we not say that?

BEN: Well, question, is it possible that the three boys are identical triplets? And so, there is some sort of roster to the stacking. Meaning, that at any given instance of Vincent Adultman, you were getting a different person in the stack order.

DANIEL: See these eyes? [BEN LAUGHS] squinting. I’m pretty sure that the genetics of these boys does not figure into the semantics of the sentence.

BEN: Okay. If we were to say that the order changes given that every time you encounter Vincent Adultman, it might be a different stack order. But you’re referring to Vincent Adultman not in a specific moment in time, but in some generic Socratic sense, like the idea of Vincent Adultman. Then they are stacked on top of each other, because you never really know because they could be in any permutation of that stack.

DANIEL: Thank you for your insight.

BEN: [LAUGHS] You’re just like, “Shut the fuck up, Ben.”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: Hedvig, go ahead.

DANIEL: Go, Hedvig.

HEDVIG: I’ve just been making this squinty face for a couple of minutes. So, I don’t think that’s how the words “stacked on top of each other” works. I think you say it about all parts, and that the last part is, it’s like people are in a line or in a queue after each other. The first person is not after someone.

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: That’s just how those things… We know that that’s how they work.

BEN: I’ve got a little stack of boardgames here, like little baby ones. These boardgames are stacked on top of each other, and no one is looking at that and being like, “Why aren’t they in a circle?”

HEDVIG: Yeah.

ELLEN: Actually, I know Jonathon a bit, and I’m pretty sure that he would not have any concern about using “each other” in that expression. That sounds like his brain operating in a way that…

DANIEL: It’s an exploration.

ELLEN: …I actually can relate.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

ELLEN: I can relate to and I enjoy it. And also, one of the main ways I got to know Jonathon was because of his position on the punctuation of non-restrictive one word of positives, because we are in agreement on that issue. [LAUGHS] He’s written about it, and I enjoyed what he wrote about it. Do you punctuate, “My sister, Susie, will be at the party,” or is it, “My sister Susie will be at the party,” that kind of thing. No comma.

BEN: No comma fan.

DANIEL: Two commas.

ELLEN: Are you all aware that you’re often told to think about whether there’s more than one sister or not? If you have more than one sister, don’t put commas. And if you have one sister, do put commas?

BEN: I was not aware of that.

[LAUGHTER]

ELLEN: Jonathon and I, I think I can say, I hope you won’t mind that I say this. I feel that we share a concern about that punctuation guideline, because it gets a little silly. Because I don’t want to punctuate my husband. But the argument, the snarky argument, is that if you don’t punctuate your husband, it means you have more than one spouse.

BEN: And in the modern era of polycules, these [ELLEN LAUGHS] distinctions increasingly are going to matter.

DANIEL: Language is a low-resolution representation of reality. [ELLEN LAUGHS] It is not intended to express things in fine detail. Good enough is good enough. So, that’s where I was going with this, actually. I was thinking, does each other have to be reciprocal? Like, if I have three boardgames in the corner and one of them is on top of the other and then the other, what if I’ve got two? What if I’ve got two boxes in the corner and one box is on top of another box? Yes, I could say, as folks in chat are suggesting, one box on top of the other. But we always say the two boxes were stacked on top of each other. I don’t think that each other has to be reciprocal, especially not pairwise reciprocal for three things.

ELLEN: Idiom. I’m just going to say the word, idiom. It’s just natural. Yeah.

BEN: Yeah, it’s an idiom, for sure.

HEDVIG: There is this lovely research project on reciprocal things. They had to record a bunch of videos where they did things like, there are four people at a table and one person is giving one thing to all of them, or everyone is at the same time giving another thing to everyone, or they’re giving in turn. They’re doing all these possible permutations of reciprocal events. There’s one when they’re chasing each other and trying to play tag, but they’re all doing this in an office building in Netherlands that I happen to have worked at, which has crazy architecture. So, none of these poor people that they showed it to on the other side of the world could always figure out what’s going on. And they’re also so funny because it’s so funny to see four people give identical objects to each other at the same time. It’s hilarious.

BEN: It seems like a square dance, but with cafes.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: And then, we turn to the left.

HEDVIG: Yeah. It’s so funny. They’re all so funny. It’s extra funny for me because there’s some of the people I’ve known, and they’re 20 years younger and really baby faced.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: But anyway, they published a bunch of different… The way reciprocal things work in different languages are not the same.

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: It’s kind of fun.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: I can recommend it.

DANIEL: The fun thing about each other constructions is the old Chomskyan sentence, “The men wanted me to listen to each other.” “The men wanted me to listen to each other,” which just hits us wrong.

BEN: Yeah, that doesn’t work in my head at all.

DANIEL: There’s something about each other that implies that whatever the action is, it has to be performed by one of each other participants. Somebody else can’t just walk into the sentence and do something to each other. It’s got to be one of the participants. It’s a really good example to point out that we know things about language that we haven’t been explicitly taught. It’s fun.

BEN: Definitely. Most things, it turns out about language that I know I have not been explicitly taught.

DANIEL: Mm. Okay. This will be one from O Tim. He’s not here right now, but he has left us…

BEN: O Tim.

DANIEL: I’m going to share a sound file. And this one came from SpeakPipe. And you know how much we love the SpeakPipe things.

BEN: Yay. It’s working.

DANIEL: I know. Little by little. Here we go.

O TIM: Hi, O Tim here. And I have a question for Ellen Jovin. I’m a court reporter in the United States, taking down in writing everything said in a courtroom or office. A dreaded non-word came up recently. A child was asked why her mom referred to her as a pig, and her response was: Mm-mm-mm. [UNCERTAIN SOUND MEANING “I DON’T KNOW”]

BEN: Oh. [LAUGHS]

O TIM: The judge immediately made the record clear, “You don’t know?” And the child answered more fulsomely, supposing it was because she was messy. My immediate reaction was, if a transcript is ordered, how am I going to spell that? And from out the corner of my brain: I heard, mm-MM-mm. [UNCERTAIN SOUND MEANING “I DON’T KNOW”] [BEN LAUGHS] How would you suggest spelling mm-MM-mm? And don’t give me the same answer my brain gave me. What would you have done, Ellen? Thank you.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: Best question ever.

DANIEL: Isn’t that great?

HEDVIG: Also, that voice, that was a good voice.

BEN: Yeah. I know. Right.

ELLEN: No, that was great.

BEN: That man’s voice is not spoken in his work, because he’s just sitting there silently recording what everyone else says. It hurts my heart.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] I asked my seven-year-old daughter how she would spell it, and she said: Mm-mm-mm. [UNCERTAIN SOUND MEANING “I DON’T KNOW”]

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Take it, Ellen.

ELLEN: I don’t have an answer for that. I’m terrible… Actually, I had issues with these when I was writing my book, because apparently, there are some standardized forms for things that I didn’t realize. Not this one. Not this one, but some of the utterances that are on the border between standard speech and sound. I can’t even think of a good example right now, but I think the copy editor led me to… Oh, maybe one was mm-hmm. I didn’t know that there was any kind of standard for that.

So, I was just free dialing it, and that wasn’t acceptable. [LAUGHS] But I don’t know. I don’t think there’s any satisfactory option there. I think I probably would do an alternation between M and N because it sounded like there was a little… Because you can’t capture the pitch changes though. So, I would just do that and then rely on the judge intervening with good sense to make sure that there’s an actual record there. I would just like to say though to that questioner that I’m very interested in the whole court reporting thing, and I’ve been trying to get gigs, because I think that seems like my kind of people. I would be interested…

BEN: [LAUGHS] My tribe.