Dr Kelly Wright is helping us understand the link between public health and language maintenance. And she’s helping us with our voluminous Mailbag!

- Why can you have a TRIFECTA, but not any other number -FECTA?

- Why does a SEXTILLION (with a prefix meaning six) have seven chunks of zeros?

- What do CHOPSTICKS have to do with chopping?

- And what’s the -ER in words like RUBBER, AFTER, and TEMPER?

Listen to this episode

Patreon supporters

Huge thanks to all our great patrons! Your support means a lot to us. Special thanks to:

- Termy

- Matt

- Whitney

- Helen

- Jack

- PharaohKatt

- LordMortis

- Elías

- gramaryen

- Larry

- Rene

- Kristofer

- Andy B

- James

- Nigel

- Meredith

- Kate

- Nasrin

- Joanna

- Nikoli

- Keith

- Ayesha

- Steele

- Margareth

- Manú

- Diego

- Ariaflame

- Rodger

- Rhian

- Colleen

- Ignacio

- Sonic Snejhog

- Kevin

- Andy from Logophilius

- Stan

- Kathy

- Rach /ɹaʃ/

- Cheyenne

- Felicity

- Amir

- Canny Archer

- O Tim

- Alyssa

- Chris

- aengryballs

- Tadhg

- Luis

- Raina

- Tony

- WolfDog

And our newest Supporters:

- Molly Dee

- sæ̃m

- and j0hntr0y, with a yearly subscription

- And new at the Friend level: Becca and Stian

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

PhD Alum Kelly Wright Awarded Best Paper in Language

https://lsa.umich.edu/linguistics/news-events/all-news/recent-news/phd-alum-kelly-wright-awarded-best-paper-in-language.html

Gurl, Am I Appropriating Black Women? | Medium

https://medium.com/tartmag/gurl-am-i-appropriating-black-women-859b679ff256

Google apologizes for ‘missing the mark’ after Gemini generated racially diverse Nazis

https://www.theverge.com/2024/2/21/24079371/google-ai-gemini-generative-inaccurate-historical

CDC Presentation: Linguistic Diversity & Public Health

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1KtuCW_iddhHUDq7uagoGQnjAeTVkY7VQwuOCwjLGGEc/edit#slide=id.g2891b0c852b_0_83

sextillion | Dictionary.com

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/sextillion

Long and short scales | Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_and_short_scales

The Possessive Apostrophe His Origin | Publisher’s Round-up

http://wmjasco.blogspot.com/2011/08/possessive-apostrophe-his-origin.html

His genitive | Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/His_genitive

Why “children,” not “childs”? | Grammarphobia

https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2016/03/en-plural.html

Move over Shakespeare, teen girls are the real language disruptors

https://qz.com/474671/move-over-shakespeare-teen-girls-are-the-real-language-disruptors

Adverbial genitive | Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adverbial_genitive

The Queen of Daytime TV

https://achievement.org/achiever/oprah-winfrey/#interview

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

DANIEL: I want to make a change to soccer.

HEDVIG: Uh-huh?

DANIEL: I like your multiple ball idea, Hedvig.

KELLY WRIGHT: Hilarious.

DANIEL: That’s super cool. I would also like to have it so that every once in a while, they unload a passel of children onto the field who try to get the ball themselves and the players have to maneuver around them. I think that would be a lot of fun.

HEDVIG: That’s good.

KELLY: This blue card thing is weird, I have to say, like, blue, I don’t appreciate that in the middle of the color spectrum.

DANIEL: What would you choose? Give me a bet… Teal?

HEDVIG: It should be orange.

KELLY: It’s like you said. It’s like orange. If it’s yellow and red, and if it’s in between… If it’s marginally yellow and marginally red, shouldn’t it be orange? I don’t… [GIGGLES] Yeah.

DANIEL: Difficult for people who don’t have as good eyesight as some of us.

KELLY: That’s fair. And it makes sense. Maybe they could just write orange, like the letters ORANGE on the card.

DANIEL: There we go. There we go.

KELLY: [CHUCKLES]

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

DANIEL: Hello. And welcome to this bonus patron episode of Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. My name’s Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. It’s linguist and friend, Hedvig Skirgård. Hedvig, where are you right now in the world?

HEDVIG: Hi. I am in my hometown of Uppsala. I can see out of the window of the room I sit now, the house that I lived in for a large number of years. That’s fun.

DANIEL: Neat.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: I’m still in a pantry.

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: All right.

DANIEL: Also, here for her third episode, it’s Dr Kelly Wright of North Carolina State University. Kelly, welcome back to the show.

KELLY: Hello, hello. Happy to be here. Thank you for having me.

DANIEL: Well, I’m really grateful to you for showing up at a horrible time for you. This is… If I’m not mistaken, it’s the hour when daylight time changes over for you. So, you found a way to make daylight time clock switching more terrible.

KELLY: This is excellent. How else would I want to lose an hour?

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: You’ll lose a lot of hours listening to us. That’s for sure.

KELLY: Oh, my gosh. I’m such a superfan. Thank you for having me.

DANIEL: Superfan. Well, now you graduate because this is your third time, and that means you are honorary cohost. Hooray.

HEDVIG: Hooray.

KELLY: Wow.

HEDVIG: Do we have the list of honorary cohosts, Daniel?

DANIEL: I do. I’m keeping a list. I know who everybody is. I don’t think we’ve really figured out… we’ve never really delved into what being a three-time host really means on Because Language. Yes, it means that you are honorary cohost. Yes, it does mean that you get the jacket, [KELLY GIGGLES] which we haven’t even made yet. Hedvig, can you please describe the jacket so that when it’s time for me to order these things, I’ll know what I’m doing?

HEDVIG: Well, I think it should be one of those American high school jackets. What are they called?

KELLY: Like a letterman.

DANIEL: Letterman jackets.

HEDVIG: Yeah. I think it should be purple. We’re coming into Easter, so maybe combined with like yellow. I like purple and yellow. I think that’s a good combo. Or, purple on purple. And it should say on the back, it should say in text of arch, it should say like “Because Language Cohost” or something like that. I think that’d be really cool. But I would like to suggest that honorary cohost or cohost, as they’re also known, should be allowed to contact us at any point and request to come on.

DANIEL: I was just going to say this! [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: And they should be privy to maybe some basic overview of the topic so that they can be like… Kelly can be like, “You’re going to talk about that? I want to be there.”

DANIEL: All right. Heads-up on topics, so that you can crash an episode whenever you want.

KELLY: That’d be fun.

DANIEL: Like, “I have free time this weekend. I’m in. Okay, we’ll do it.”

KELLY: I may or may not have like a notes file for when I listen of just like, “Maybe this will organically come up.”

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Okay. That’s fine too, because it’s always fun to get news content or something.

DANIEL: Yup. Okay, we’ll do it. This is not going to be ready by Easter, by the way, jackets.

KELLY: [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: Just saying. Okay. So, Ben isn’t here for this one. He sent me an audio file of his voice today and here’s how it sounds.

BEN: [SINGING] Smelly cat, smelly cat. What are they feeding you? [SPEAKING] Unfortunately, this is my voice. This is not a good podcast voice. I don’t think I’ll be able to do the podcast with this voice.

DANIEL: Yeah. So, that’s Ben. Doesn’t sound good, does he?

HEDVIG: I don’t understand. I thought he sounded good, but I think it’s more important if he feels bad than what he sounds like.

DANIEL: That’s right. Because in a relationship, if there’s a perceived problem, there’s a problem.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

KELLY: Correct.

HEDVIG: But I thought his voice sounded fine. But who cares?

DANIEL: There was detectable levels of raspiness. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: Yeah, but that’s attractive.

KELLY: Right.

HEDVIG: Like, I don’t get it.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES] Smoky.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: I think that as the hour progresses, he would have sounded worse and worse. Maybe if it means that he can teach tomorrow, maybe it’s worth giving him a hiatus this time. And anyway, we’ve got Dr Kelly Wright. Kelly, first of all, congratulations on your award. 2024 Best Paper in the journal Language. That’s huge.

KELLY: Thank you.

HEDVIG: That is pretty…

KELLY: It’s pretty huge. Thank you so much. I was so grateful to be able to receive the physical award from Dr John Baugh at the LSA Annual Meeting, which… I couldn’t have done the research without him. So, it was a great full circle moment. [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: That’s gorgeous.

KELLY: Yeah, it was awesome. And I get to celebrate it all year. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Yes, you do. [CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: And for the listeners, maybe to put it in a bit of context, the Journal Language, which is published by the Linguistic Society of America, despite its publisher, does also publish by non-American linguists. Linguists not at American universities. But it is one of the absolute largest journals in our field, and it is not easy to get in and out of all of those people who get published, to get this award is pretty big deal. So, very well done.

KELLY: Yeah. Thank you. Yeah. No, it took seven years to get the paper published. So, I’m really happy that they liked it after all of that effort. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Yeah, you talked about it with us on the first episode we did together where you helped me remember, because you’re actually kind of tri-dialectal here. I’m going to hand it off to you.

KELLY: Okay.

DANIEL: Help me out.

KELLY: Yeah. No, you’re right on track. It’s so right. I called 90 landlords using three different voices, my three different voices. So, African-American English, Southern American English or Appalachian, and Standard. Yeah, we see really varying results based on which voice you’re using, essentially that neighborhoods that have a character, kind of maintain that character. So, a Black neighborhood wants somebody who sounds Black. A white neighborhood wants somebody who sounds white. Middle class neighborhood wants somebody who sounds Standard.

And the recordings that I did were for the perceptual side. So, the whole perceptual experiment is like not the actual people I called, but just a general listener, how they react to that voice.

DANIEL: I want to talk about the work that you’ve been doing lately in linguistic diversity and public health. But first, I just wanted to ask you a weird question, because this question has been kicking around for me. And, Hedvig, I’m going to ask you the same question. Are there any news stories you’ve noticed that you’re weirdly obsessing over lately?

KELLY: Okay. So, I love this question. Not news stories per se maybe, but there’s like this meme or like TikTok trend that’s been going around that is, folks, I guess like marveling at the fact that they’re saying that Black slang is white slang in reverse.

DANIEL: Oh, I haven’t heard this one.

HEDVIG: Okay.

KELLY: So, it’s this thing of like, white people say, “I’m in.” And Black people say, “We out.”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

KELLY: Or, like, “You’re messing with the wrong person,” versus, like, “You got the right one today,” that kind of thing.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES] Right.

KELLY: It’s like, white slang is Black slang in reverse.

HEDVIG: That’s so funny.

KELLY: I cannot convey hard enough that it is the other way around, that Black slang is first and white slang is 100% in reverse, or reacting to that, or you get HOT instead of COOL, because COOL came out of Black slang first, and then everyone started like, “That’s hot. That’s this.” Yeah, it’s the other way around. It’s driving me crazy. So many people keep sending me this TikTok, these memes, and they love me, and they know that I’m interested in this kind of thing. But I’m like, [SQUIRMS] I’m obsessed with why this is such a persistent idea. And people in these TikToks are just marveling at it. Like, “[GASPS] Oh, my gosh, you’re so right. This is how language works.” [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: As a non-American, can I ask like…? So, there are a couple of these pairs like HOT and COOL, and IN and OUT. I went to a talk recently about directionals at IN and OUT and how they work in grammar in some languages. And the funny thing is that in a lot of languages, you get that no matter what the directional is, if it’s like upstreams or up or down, it becomes… How to say it? It becomes a certain grammar marker, even if it’s away or toward. Like, the thing is movement. So, is it that it’s hot and cold, or is it just that it’s extremes, if that makes sense?

KELLY: Yeah, that’s a good question. It probably is more about that underlyingly, semiotically, pragmatically, something more about extremes than it is about directionality itself or degree. Or, like conscious opposition. This thing about it being white slang being Black slang. There’s like a secret cabal of white slang makers sitting around being like, “Ha-ha-ha, turn it inside out,” or whatever.

[LAUGHTER]

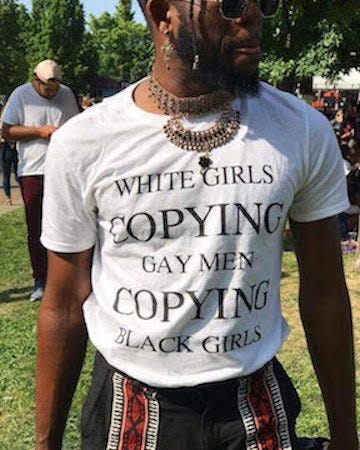

DANIEL: Well, I think there might be something to this meme. Let me just share this picture. And it’s fairly well known. It’s a picture of a Black man wearing a t-shirt that says, “White girls copying gay men copying Black girls.”

KELLY: Oh.

DANIEL: Is there anything to this?

KELLY: I think so, a little bit. A lot of what we’ve been doing in the dictionary recently too, has been, we did a special edition on gender and sexuality. We’re currently working one for the Word of the Year. And a number of these terms are very that of like, they were nominated because white women found out about them. [GIGGLES] But it is like this progression.

DANIEL: Constant problem.

KELLY: Yeah. The last thing of that is dictionaries finding out about words, because…

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Yeah. Be a very long shirt, wouldn’t it, eventually?

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Hedvig, same question. Have you noticed anything? What’s been kicking around your mind linguistically that you’ve found?

HEDVIG: Linguistically. Well, I’m just really deep in the basics right now. So, I have been teaching intro to linguistics. So, I’ve been like, “What is a phoneme?”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: And also, not news at all, but just like… And the students are challenging me by asking very smart… This is the same problem I have with our listeners.

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: I need our listeners and my students to not be so smart, because it’s very tiring for me.

DANIEL: Meet their level. Meet them at the level they’re at, Hedvig.

HEDVIG: Yeah, I know. No, I’m trying. I’m trying.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: But they’re asking very clever questions. And there are cases where the linguistic framework fails because it’s a generalisation that doesn’t take into account all kinds of exceptions and nuances. But anyway, I have not been thinking so much about linguistics news, unfortunately. I did see something that I was unsure what to do with, which is about words for snow.

DANIEL: Okay. Classic.

HEDVIG: Because… Yeah. And I feel like I would like to issue a call to everyone that Berlin and Kay established basic color terms. Like, they should be words that aren’t just like, “Oh, this color is like an orange. It should be a term that only refers to the color and it shouldn’t be a combination of other terms like light blue. It should be something.” And I feel like everyone who works on languages in places where there is a lot of snow need to establish a basic snow term, because they seem to just rack up compounds, maybe. Anyway, that’s what I was thinking about.

DANIEL: Oh, I see.

HEDVIG: The snow term. Because now, recently, someone said that Sámi has 500 words for snow, and I fully believe that there are 500 dictionary items. I just don’t know if it’s comparable to other snow lists. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. I don’t know. [MUMBLES]

DANIEL: I don’t know Sámi, but I know that for polysynthetic languages, where it’s okay to clump a whole bunch of different things into a word. Yeah, there would be 500 words for snow, but they would be words that encompass entire sentences in English. So, we have 500 sentences for snow or 500 phrases that could involve snow.

HEDVIG: Right. Yeah.

DANIEL: It’s a function of how the language works.

HEDVIG: Yeah. And that’s what I’ve been thinking about. Yeah. What have you been thinking about, Daniel?

DANIEL: I’ve been thinking about the way that white people suddenly discovered racism.

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

HEDVIG: Oh, we did? Again?

DANIEL: They found a version of racism that they don’t like.

HEDVIG: Oh.

DANIEL: Racism against white people. That’s right.

HEDVIG: Wait, Daniel, you and I are white and I don’t think… Who found this? What is this? What…?

DANIEL: Well, here, I noticed a couple of things. First of all, the photo generator, Gemini…

HEDVIG: Um.

DANIEL: …people have been giving examples of how it steadfastly refuses to represent white people even when you would normally. It’s like, “Show me, please, a photo of two affluent people in 15th century Bavaria.” And it’s like a Black guy and an Asian woman walking around in 15th century Bavaria. It’s like, “Why are white people not being represented? The underrepresentation of white people is a constant problem!”

HEDVIG: I think I know why this is. Correct me if I’m wrong, but what I’ve understood is that like, the way these AI models work, be they generating images or video or text or something, is they learn from a lot of data. They learn from our biases. So, if we keep publishing certain kinds of images or text, it’s going to publish it. So, if you’re asking, you are like, “Who scored the most goals in football ever?” It’ll say Chris… whatever his name is, even though it’s a woman, because he is talked about more as scoring more goals. So, that model is like: That must be the person who scored the most goals.

It doesn’t have an understanding of reality, because if you asked it like, “How many goals did this woman score?” It will say a higher number, but it doesn’t understand that numbers are things. It just repeats what we get back to it. So, the problem that Google and everyone else OpenAI is having is that they’re getting all these biases spit back. So, they’re putting on… They don’t know what’s happening in the black box. So, they put on a filter layer afterwards where it says like, “If you are asked to produce a picture of a person, please make sure that at least one face is of any one of these minorities in the US.”

That’s what’s happening, because it just knows that it’s going to run into these biases. And these hard coded little secret prompts, which you can secretly try and elicit, are the ones who are inserting, for example, Asian folk in 1500 Bavaria. So, we’re shooting ourselves in the foot and then being like, “Who shot me?”

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Like, I don’t know what to tell you. Go to Wikipedia, if you want real knowledge.

DANIEL: Kelly, what’s your perspective on this?

KELLY: I think it’s interesting. I definitely have a perspective, at least like lexically, that we have to let people encounter meaning where they are. We very much accept that. Folks don’t know the entire history of a word when they use it, and that things can be employed cogently out of context. So, I feel like it’s possible that people are encountering racism for the first time in this way, [GIGGLES] that maybe that discrimination is best understood when felt, and maybe this does feel discriminating. But all of that, diplomacy aside, it’s fascinating. I think this goes back to the whole, like: “a mermaid can’t be Black” thing of like, “This isn’t reality.” We’re talking about like AI generated image.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

KELLY: Like, this isn’t reality. Are you sure you’re that mad? [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Yeah, that’s a good point. Because I feel like if you wanted a picture of 1800 farmers in Bavaria, go to Wikipedia and look up an actual historic picture of people in Bavaria farming. Why are you asking Gemini for this? [KELLY GIGGLES] It doesn’t know anything about the world.

DANIEL: Because they were trying to trip it up, that’s why. Okay. Well, thank you for entertaining me on that score. I want to move now to talking to Kelly about her work. Kelly, you’ve been doing lots of invited lectures. And I was really curious about the one that you gave to the Center for Disease Control, the CDC, in the USA. Your talk was about linguistic diversity and public health. Tell me what they had to do with each other.

KELLY: Yeah, a surprisingly large amount. I was really excited and fortunate to be asked to do this talk, because it made me go back to all my research and think really closely about it. And a lot of what we’re talking about now, automatic speech recognition is this area where my research encounters the world of tech and begins to ask the question of like, “If your data set is not fully informed, if it’s not fully representative, what does that look like down the line when you’re trying to solve real world problems with an uninformed software?”

And public health is very much where the rubber meets the road on that. And we see like, “Okay, people are actually these linguistic ideologies that we see play out in everyday interactions,” or, “We have these examples in our literature of the most dire consequences.” That is like an everyday issue when people are trying to interface with this large government body that is supposed to be protecting everyone who falls under the United States purview. So, we’re counting all of our territories here as well, protecting them in all of the aspects of public health. So, just access to regular care, but also like clean water.

Most of those languages that exist in the US are not supported by CDC apps. They also never exist in official paperwork. So, you can get your prescription information from Walgreens printed in 10 or 12 languages, but it’s not the hundreds that our borders hold. And so, it was interesting just speaking to nonlinguistic experts about what we do and how we can help inform their inclusion efforts, and what inclusion efforts internally to the CDC can look like applied to their products and initiatives. It was a lot of fun. [CHUCKLES] And also scary. Always a little scary. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Why, because you’re in a room with people who…? Did you feel the weight of the influence that you could have?

KELLY: Not exactly that. It’s just like, okay, wow, this is actually… Again, looking at my work from another perspective and being like, “Okay. Really, people…” I’m always trying to convey to folks like, “Here’s this large theoretical problem that puts people at acute risk.” Like, “Here are discrete risks that occur from just having your name mispronounced,” basically every day of your not even adult life. Like, since you were a child. A lot of people, what it means to give up on insisting that people use your name correctly or that recognise you as someone who’s worthy of having [LAUGHS] a speakable name. These things, over time, can reduce the effectiveness of our immune system.

DANIEL: Oh, my gosh.

KELLY: It’s like, not even just people think anxiety, which obviously also hurts. But it’s all of these things combined, it’s like a death of a thousand cuts. So, I was able to encounter new research and see all the stuff and be like, “Okay, I need to be putting this in every talk I give,” because people just don’t maybe think like, “Oh, you had a bad day,” or, “This was an emotionally difficult moment for you.” And it’s like, “No, people encounter these moments every single day in lots of ways.” In lots of ways, we don’t even think about. In ways that are not as serious as having the door of an apartment slammed in your face, or being incarcerated, which is like the stuff I usually think about. So, yeah.

HEDVIG: I’ve been thinking about this, because as we are in the UNESCO Decade of Indigenous Languages, linguists always talk a lot about minority languages and sustaining them and things like that. But teaching this course recently, there are two things that I thought made some of these things more concrete for me. One of them is the effects of, for example, not getting access to speaking your language or getting access to your culture or being recognised as a part of that culture by other people can have not only psychological, but also sometimes physical effects.

I read some meta studies on people in Canada who had access to their heritage culture and not. And they found some health outcomes that it could have an effect on things like diabetes. Or, like, if you are psychologically stressed, you will also sooner or later become physically stressed. So, these things are actually linked to health outcomes quite directly in a way that I think people don’t realise.

The other thing is that… How to say this? We’re linguists, right? I talk about language, and I’m interested in words and grammar and things like that. It is true that when people talk about linguistic justice, it sort of feels sometimes like language is becoming a…

KELLY: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: It’s not just about the language, because it’s also about the culture and the history and the identity and everything else. And language is just like one signifier of that. Do you know what I mean?

DANIEL: A proxy.

HEDVIG: Because we were talking with my students like, “Oh, what if Swedish people didn’t speak Swedish anymore but we celebrated all of our cultural heritage, and we had all of our literature translated to English? What would we lose?” We wouldn’t maybe lose that much, because it’s just the language. But that doesn’t happen. People don’t lose just the language. They lose everything at once. And so, much more than just language. And it does have a very real effect, including health wise. I think sometimes when linguists talk about language, it becomes too abstract. So, I appreciate thinking about it like that.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s a good point. Let me just sharpen that a little bit, because way back when, I think in 2017, we did a story about how some linguists in Canada had found that when Indigenous people have access to their heritage language, they see better health outcomes. That’s the story that you mentioned, Hedvig. And they at the time said that the effect stayed even when they accounted for other variables like education and economic status and occupation and things like that.

But then a couple of years later, we found another study from a team at ANU, and their findings were that there wasn’t much evidence of a significant relationship between Indigenous language use and physical health. What we came away with from that episode was that wellbeing that connects to language is probably serving as a proxy for other kinds of wellbeing. That is to say, when, for example, a government is committed to preserving or maintaining Indigenous languages, it probably also means that they are committed to wellbeing in other areas too. Still, supporting Indigenous language is very important, but it’s only one thing that we need to do to support Indigenous people.

HEDVIG: Like, it makes perfect sense. Who thought it was just like, you don’t get to say this word. Therefore, it is not…

KELLY: Right.

HEDVIG: Why would it be that? Of course, it’s everything.

DANIEL: Yeah.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: It’s everything.

HEDVIG: Yeah. We don’t see you as people. You don’t get to do your cultural thing. You don’t get to dress. You don’t get to be treated like a person. Like, it’s all of those things together. And it happens that an easy thing to measure sometimes is language.

DANIEL: Yeah. As well as if somebody has the means to study their heritage language, they’re probably slightly more affluent in other ways. But hey, let’s attack socioeconomic inequality and language. Let’s do it all.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: Just before we go on, what were your recommendations to the CDC? [KELLY GIGGLES] How could they lift their game language wise?

KELLY: Well, okay, so, I talked a lot about, yeah, these things that we think are really small, like something like mispronouncing someone’s name. They asked me for some practical applications. I really encourage them to create space for people who want to insist on a certain pronunciation to allow for that and to also maybe include it in… make it, like institutional practice. So, the ways in which we’re sharing our pronouns on our email signatures or office doors, to also include pronunciation guides. And I gave them several examples, because a lot of professionals that I know have that on their email signature even or on their website about how you pronounce my name.

Yeah. And just something that simple, like creating space where there just is a more egalitarian acceptance of just forms, just linguistic forms, something like a retroflex R. Let’s just let it exist. [GIGGLES] That kind of thing, I think is really helpful internally of just build this culture of acceptance. I really didn’t talk much about their general initiatives. I know that they’re trying to build a more informed listening app. I talked to them a little bit about why automatic speech recognition is incredibly fraught and how investing in these documentation efforts that are trying to build out the database for a lot of these large language models to just include writings from, I don’t know, women or disabled people.

DANIEL: All right. Well, thank you once again for talking us through that. It’s super interesting, and it’s a super important area for not just people’s happiness, but also their lifespan.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: All right. You ready to tackle some questions with us? Because we got a lot of questions from people.

KELLY: Yes.

DANIEL: Okay. Here we go. This one is from robin turtleson, who asked us on Twitter. “Why is trifecta a word, but there are no similar words for other numbers? I just used hexeffecta in a conversation. People knew what I meant, but then I looked it up and it’s just not a word. Help.” Can we help Robin?

HEDVIG: Right. Well, first we got to say what trifecta is. It’s a similar thing to a triple threat, right? Like, it’s three things in common. Like, “He can act, he can dance, he can sing. He’s a triple threat.” A trifecta would be like, Daniel can make decent coffee, can record podcasts. And what else can Daniel do? I don’t know. It’s not a lot.

DANIEL: That’s about it.

HEDVIG: That’s about it.

DANIEL: Give me some time. Give me some time.

KELLY: Figure that.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Yeah, he’s a dufecta. Trifecta is when three things come together. I think trifecta can be positive or negative. Is that right?

KELLY: Yeah, I think contextually applied, you could be not so fun trifecta.

HEDVIG: Oh, like when you have your period, covid, and get dumped at the same time?

KELLY: Right.

HEDVIG: Something like that?

DANIEL: Yeah. Okay.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: That’s a trifecta.

HEDVIG: That could be a trifecta. Right, okay. So, the question is, why is it TRI-, and why don’t we care about double or four? And the word that Robin made here, we should explain maybe HEXAFECTA, that would be six things at once, right?

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: But that requires people to know Latin and or Greek roots, which is not common knowledge. So, people might know like a hexagon, and they could count that, “Okay, hexagon. Six side.” Yeah, why is it three? I don’t know.

DANIEL: SEXFECTA might raise a few eyebrows if you tried going with that prefix. Kelly, what do you think?

HEDVIG: Hexafecta?

KELLY: It’s fascinating to think about TRI- in this way, because you have other words like TRIUMVIRATE and TRINITY.

HEDVIG: Uh-huh.

KELLY: And it’s like, why don’t you have like DINITY or QUADRITY?

HEDVIG: Yeah. Why isn’t it FOURITY?

KELLY: [CHUCKLES] Yeah, triumvirate, like this idea of a three-person governing body. Maybe it has something to do. I realise that language doesn’t often work this way, but maybe it has something to do with the triangle being like a baseline shape. [CHUCKLES] It’s just something we think about… Because we do a lot of threes.

DANIEL: It’s true.

KELLY: Examples of lists of threes of things…

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: …that when we’re being descriptive. And so, two adjectives never feels like enough. Four feels like too much. So, maybe this has something to do with… The trifecta of being like, “We’re always only going to give you three.” [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES] Right.

KELLY: “We’re often only going to give you three points.” I don’t know. It’s interesting.

HEDVIG: I think you’re right. When people learn rhetorics, they write like a paper, you present your argument, you present three supporting things for it, usually, that’s really common. I guess with people, it makes sense with three, because then if there were three people who needed to decide about something, you don’t have an even number, so you always get a decisive. There’s always two people against one.

DANIEL: The power trio. Yeah. Okay.

HEDVIG: Whereas if you have two, they could just argue forever. So, you want to have like three or five or seven or something.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: Much over three, it’s a little bit hard. I know that a lot of languages… We have a word for two times, it’s TWICE. And three times is THRICE. But after that, we give up. We don’t have QUICE. Nobody does that, right?

KELLY: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Some sort of cognitive limit.

KELLY: It’s like, why are you still trying at this point?

[LAUGHTER]

KELLY: Like, QUICE.

DANIEL: QUICE?

KELLY: [LAUGHS] I like that.

HEDVIG: In pronoun system, you often have numbers. You have like singular, plural. And if you got more than that, you have dual. You might have trial, but you very rarely get quadril, right?

DANIEL: One, two and many. That’s what you get.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

KELLY: A quadrille in square dancing. [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: That’s true. That is one.

HEDVIG: Oh, okay. Yeah.

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: And bands tend to be successful if they have four people or five people. So, that’s a little counterexample. But I decided to do a little bit of digging on this one and find out where the word TRIFECTA comes from. And it comes from the world of horse racing.

HEDVIG and KELLY: Oh.

DANIEL: So, we have to start with the word PERFECTA which we see from 1961. And I’m going to read the first quote from the OED, the Oxford English Dictionary, about PERFECTA. “A form of parimutuel betting, also known by other names as exacta, correcta, etc., in which a pair of animals or players are selected in a single event.” In other words, you don’t just have to guess the winner. You have to guess the winner and the second-place finisher, and then you’ve won the perfecta.

KELLY: Okay.

DANIEL: Or, the correcta.

DANIEL and KELLY: Or, the exacta.

DANIEL: I don’t know why the -A was there. Maybe to make it sound Greek or interesting or something, I don’t know. But then what happened next was the game evolved, so that you had to pick three horses, not just two. So, by 1977, we see the trifecta. “To win the trifecta, a bettor must select the first, second and third place horses in order.” So, that’s how we got TRIFECTA. It was horse racing.

KELLY: Wow.

DANIEL: In theory, there could have been other -FECTAS, but horse racing just didn’t go that way because picking four horses correctly would be super tough. That said, I am seeing QUADFECTA popping up in various places. So, it does appear to be a combining form, -FECTA.

HEDVIG: I was going to say like, when you have any race, you have… How do you say it? You have gold, silver, and bronze. And you have the little podium, right?

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: And you only have that for first, second, and third.

KELLY: Right.

HEDVIG: Nobody cares who came fourth or fifth.

DANIEL: Nobody cares.

KELLY: That’s correct.

KELLY: Also, I’m now thinking about horses on podiums, which I love.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah. Exactly. I’m just thinking about a really big podium with eight people in different orders. So, TRIFECTA has evolved away from picking horses, but it still has the implications of getting lucky, doing three things right or doing three things really well, or sometimes having three very unlucky things happening. It could have gone that way, but it just didn’t because I think three is an upper limit cognitively. But also, the sport, we just didn’t care who came forth. Thanks to robin for that question.

Let’s go on to one from James via email. James says, “Just received the game, League of the Lexicon.” We had an interview with Joshua Blackburn of Two Brothers Games. That was a fun one. “Just received the game, League of the Lexicon, for Christmas and learned that sextilion means 1,000 to the sixth power in British English. But in French and US English, the seventh power.”

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: “How can this come to be when the etymology clearly looks like it has the SEX- root? I am guessing from romance languages.” James continues, “Is this a question of different Englishes? I suspect foul play and will be grateful of your kind assistance in the matter.” What do either of you know about very large numbers?

HEDVIG: I know that in Swedish and English, there are a couple of mismatches as well. So, what you call billions, we call miljard. I know that this is like confusing things in more things. If you actually care about numbers, you should not use words for numbers. You should use Arabic numerals.

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Or, say how many zeros you’ve got.

HEDVIG: I actually like when people say how many zeros, because it’s one and so many zeros. Because also James wrote like 1,000 to the sixth power, which means I now need to think about that kind of math, which is not my usual mode.

DANIEL: No, me neither.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

KELLY: There are several interesting mismatches. Like, Turkish has one too. I think some of the counting systems… I wonder if it is like this difference in some of the counting systems where after 20, and the numbers are these weird… They’re more like fixed. They’re not going to respond to variation as quickly or as robustly or even in the whole system at once which… yeah, it’s interesting history in our numbers anyway.

DANIEL: Oh, big time. Well, this is about the short scale and the long scale. So, I’m just going to try to keep this simple for our listeners. When I talk about three zeros, I’m going to call that a chunk of zeros, okay?

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: So, 1,000 is one chunk of zeros. That’s three.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: A million is two chunks of zeros.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: A billion could be three chunks of zeros, but some people think of it as four. Okay.

HEDVIG: No, no, no, no.

KELLY: Because like 100 billion or whatever.

DANIEL: Okay. So, Americans would call four chunks of zeros a trillion.

KELLY: Right.

DANIEL: But other folks in the world might call it a billion and things get nasty. Okay, I’ve already lost Hedvig.

KELLY: She’s like, “What are the numbers?”

HEDVIG: I don’t like it.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, let me start over then. Because I think the problem here, the mismatch, is that 1,000 is one chunk of three zeros. A million is two chunks. A billion is three chunks. But see, there’s the problem. The BI- suggests two, but we’ve given it three chunks of zeros.

KELLY: Interesting.

HEDVIG: It’s just that it’s after million, and million is the unofficial one there.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: And then it’s BI-, because it’s the next one after million. And then, it’s TRI-, because it’s the next one after BI-.

DANIEL: And we’re out of sync.

KELLY: And we’re out of sync.

DANIEL: If only we had called the first chunk of three zeros — which we now call 1,000 — if only we’d called that a million and then the second group of three zeros could be a billion, then it would have worked out. But now we have a billion, three chunks of zeros. A trillion, four chunks of zeros. And it’s all wrong.

KELLY: Wouldn’t that have been, like, a bousand? [CHUCKLES] Sorry.

DANIEL: A bou…

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: …a bousand.

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Actually, the funny part is that it’s called a million, because the -ON suffix, which means “a big one”. A MILLE is 1,000. So, a milli-on is a big 1,000.

HEDVIG: A big thousand.

KELLY: Oh. Okay, that makes more sense.

HEDVIG: That’s helpful. That is helpful. Okay.

DANIEL: But here’s how we got here. We mentioned in an older episode that numbers haven’t been consistent across the different varieties of English. It used to be that they would group zeros in chunks of six, not three. You know how we put a comma after three zeros? They didn’t do that.

KELLY: Six figures.

DANIEL: They put a comma after six. Yeah. So, then the million was the first one. And then, if you got 12 zeros, that was their billion. And that really did work, because that was like two chunks of six. There’s your billion, right? And then, a trillion, three chunks of six. And that was the way that a lot of people did it, and that’s how they did it back in 1475, French mathematician, Jehan Adam, writing in middle French…

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: He used chunks of six. First one’s a million, second one’s a billion, third one’s a trillion. With every chunk of six, the name would go up. But then in the 1600s, people switched. They moved from a comma every six zeros to a comma every three. And the names picked up and ratcheted across, but only in some places.

KELLY: So wild. I wonder how much the printing press had to do with this, the movable type played into that. Anyway.

DANIEL: And once again, three. Maybe…

HEDVIG: I was going to say, what’s up with three? Why not hundred-two of them? Or, why three? Why not four?

DANIEL: Cognitive limitation. Although Japanese does use four. Japanese uses maan. So, that’s tricky for me.

HEDVIG: Right. Yeah, why three?

DANIEL: It is confusing. Nowadays, most of the English-speaking world has settled on chunks of three. It may be a little confusing, but if you think you’re confused about long and short scales, try being Canadian, where the English-speaking people do short scale, and the French-speaking folks do long scale in the very same country. Aaargh. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: That is rough.

KELLY: And yet, commerce prevails.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Yes, it does.

KELLY: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: In French, they have funny ways of doing some numbers, because they say 4 times 20 is 80, which is a little bit long. And 90 is 4 times 20 plus 10, which is like a lot of things. But of course, they’ve lexicalised it. So, “quatre-vingt dix” is like one thing in their heads. But I’ve been told that one of the reasons that the Swiss French don’t do that, they actually say nonante, which is 90. More similar to 90. It’s because when you’re a company that has a lot of interest in the finances business, you don’t want to be misunderstood on the phone. When you say, like, “I want to invest 90%, blah, blah, blah,” you don’t want confusion.

KELLY: Forty-twenty-ten percent, please.

HEDVIG: Right.

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

HEDVIG: Let’s say, there’s a shaky telephone line and you don’t hear one of those syllables. So, that is the folk etymology of why Swiss people say nonante instead of quatre-vingt-dix. But that might be a fun story people have made up. I don’t know.

DANIEL: I don’t either.

KELLY: That’s fascinating.

DANIEL: Good for you.

HEDVIG: Yeah. Kelly does the dictionary person nod of like: yeahh.

KELLY: [CHUCKLES] One of the best things is folk etymology, is like, where does meaning move away from? Does it mean what they tell us or does it mean what we document? [CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Delicious. Thanks, James, for that question. Now it’s time to move on to our favorite game, Related or Not. I put out the call for theme songs, because we would like to have one. And our good friend, Adam, listener and friend, generated a few using suno.ai.

HEDVIG: Oh.

DANIEL: Uh-huh.

HEDVIG: Thank you, Adam.

DANIEL: All you have to do is do a prompt. You have to type some text, like say the style that you want. Here are the lyrics. So, Adam used something that Ben sang when he was just improvising one of his themes and being funny. And the words were “Related or not, is it connected to the word or the other word?” That was what Ben said, so Adam went with it.

This isn’t what we’re going to go with, but Adam and I were having some fun. We were laughing about this and trying not to take it too seriously and not getting concerned. But this is all from text. So, let’s hear this week’s Related or Not theme.

[RELATED OR NOT THEME, IN TRAP STYLE]

KELLY: I love it. It goes so hard. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: I think it slaps. Yes, it goes way harder than it had to.

KELLY: It’s so good. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: And no human singers.

HEDVIG: [SINGS] Is it connected?

KELLY: Yeah, that’s weird.

HEDVIG: That was weird. That was fun. I enjoyed that.

DANIEL: I did too.

HEDVIG: And it sounded like a voice. Like, it sounded surprisingly human-y.

KELLY: Yup. That uncanny valley.

DANIEL: Yup.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, Adam, thanks so much for that theme song. We will be listening to more of them. Here’s the first one. This one’s from Cara on our Discord. And it’s FAULT. Kara asks, “Related or not, FALTA, the lack of something in Spanish, and FAULT, guilt in English. So, in Spanish, if you say something is missing, it’s like, “Oh, me falta un lápiz.” I’m missing a pencil. And then, there’s FAULT, which means a lot of things in English. One is guilt, but one is some sort of character flaw or something like that. So, are they related or are they not? I have made my guess and then I looked it up.

HEDVIG: There’s also the FAULT, like a technical geology term, right?

KELLY: Right.

DANIEL: Oh, yeah. Like an earthquake.

HEDVIG: Yeah. I’m going to just disregard that for now.

DANIEL: I do think those are related in English but okay.

HEDVIG: Right. Well, if they’re related, then “missing” and “gap”…

DANIEL: Oh, you’re finding a semantic link there! That’s really cool.

HEDVIG: And I know that French has “Ce pas ma faute.” Like, “It’s not my fault,” which sounds similar.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. It sounds like you’re l…

KELLY: But it’s… all of that’s just a smokescreen.

DANIEL: Sounds like you’re leaning into it. You’re thinking related.

HEDVIG: Yeah. But that is making me think that…

DANIEL: Don’t be afraid. [CHUCKLES] You can really go in circles that way. You can really…

HEDVIG: Yeah, exactly.

DANIEL: …do a number on your head, right?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: All right. Kelly, what do you reckon? Which way are you leaning?

KELLY: I’m leaning the other way. I think maybe not related, because if a FAULT in Spanish is a lack of something, then it’s my fault… If you’re guilty, what are you lacking? Innocence? That feels like a reach. I don’t know, I would say that FAULT, like, “I made a mistake,” or, “I caused a rift,” or something is more related to the geological term than it is the Spanish term. So, I’m feeling like maybe it’s too different. That’s just a guess. [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: In my own head canon, when I was learning Spanish, I always linked them. I always thought they were the same. And anyone who knows me knows that when I have always believed a thing, I continue to believe that thing. So, I said, yes, they were related. Hedvig, are you yes or are you no?

HEDVIG: I can see the semantic connection, because I think that when it’s your fault, you are lacking in rightness or something is lacking in your personality or something like that.

DANIEL: A character.

HEDVIG: You are not meeting the situation. But I have a galaxy brain problem. I can find semantic connections between anything.

DANIEL: Okay. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: I have looked at too many different languages, and my brain is very stretchy.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: So, I think I should go with Kelly and say they’re not related, because I think we’re being led up a garden path.

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: That’s what human brains do, you know. They see connections between things. All right. So, I said yes. You both say no. Answer, they are related.

HEDVIG: Oh, darn it.

KELLY: Amazing.

DANIEL: They can both be traced to vulgar Latin, FALLITA, a shortcoming or a failing. And that comes from Latin, FALSUS. They are related.

HEDVIG: Oh, FAULT is like FALSE.

DANIEL: Yes. They are both related to FALSE as well.

KELLY: That’s cool.

DANIEL: So, that’s something wrong.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay. Let’s move on. LK is doing some galaxy brain thinking here. Have we done this one before? Related or not, the -S suffix for plural.

HEDVIG: Oh, which one?

DANIEL: And the -S suffix for third person singular.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: Like, “John eats”.

HEDVIG: Because I had to talk to my students about this because it’s really like polysemy or whatever, or homophony, like things accidentally being the same or things being the same because of etymology is happens all the time. I didn’t look it up, but I was talking to the students. I was like, “We have possessive -S in English, like Hedvig’s book. We have, like, she sings a person tense third person, and then we have a plural -S.” They’re all doing quite different jobs, but they all have just an -S. It’s funny with English, because it’s really like -S is the letter everything is going to converge on.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: So, now you’re asking me if the plural one and if the third person singular present tense is related. Those are the ones we’re being asked about?

DANIEL: Yes. I decided to ignore possessive -S for this one.

HEDVIG: Okay. All right. Well, it’s third person singular and it’s plural.

DANIEL: Yup. They’re different things.

HEDVIG: So, I’m going to say no.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: I don’t know.

DANIEL: Because singular is not the same as plural.

HEDVIG: Kelly, what do you think?

KELLY: I feel like I do somehow… deep from the history of English class in 2012, [LAUGHS] remember that the possessive -S is different, that it comes from a different place, because maybe it was… I don’t remember. Wasn’t there a whole word we used at some point of English, and now it’s just an -S, like it’s been reduced? I don’t remember.

DANIEL: I do know this one. So, the origin of the possessive -S in English, it really does come from an old English ending. So, for example, if you wanted to say “the king’s ship”, it would be something like “se cyninges scip.” And the -ES, that would eventually become the possessive -S.

It’s not true that we got it by people saying “the king, his ship”. However, I was surprised to find out that there has been this fad in English a little bit around the 1200s and then again in the 1500s, where people got this idea that instead of being from Old English, people thought that that possessive -S was “his”. So, “the man his book”, or “the king his ship”. For a while, you can find people actually writing the his genitive. That’s the name it has, the his genitive. But by the 1600s, it died out. We don’t do it anymore. It’s not how possessive -S came about, but it was an interesting thing that people did write down sometimes.

KELLY: So, I’d think that the other two -Ss are related.

DANIEL: Oh, okay.

KELLY: Yeah. [CHUCKLES] But it’s a straight guess.

DANIEL: Okay. Cool, cool.

KELLY: [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: I thought nah, not related. I wrote, “I’m positive that they came from different old English endings, different inflectional suffixes.” That’s what I thought.

KELLY: It makes sense.

DANIEL: Okay. Bit of history on this. So, plural -S comes from old English -AS, and it was nominative plural for many nouns. Not all of them. There were lots of ones where you would pluralise with -S, but there were lots of ones that you would pluralise with -N, like your EYEN, and you could still find 100 years ago, MINE EYEN.

HEDVIG: We still say that.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: Wait. Hang on. How does that go?

HEDVIG: [IN SWEDISH] Ett öga. (one eye)

DANIEL: Uh-huh.

HEDVIG: Två ögon. (two eyes)

DANIEL: Cool.

HEDVIG: Ett öra. (one ear)

DANIEL: Uh-huh.

DANIEL: Två öron. (two ears)

KELLY: Nice.

DANIEL: Awesome. One child, two children.

KELLY: Oh, yeah.

HEDVIG: Ett barn, fler barn. (One child, more children) They’re a mass noun.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: They are a mass noun.

KELLY: Awesome.

DANIEL: Big pile of children around the place. Okay. Now that we’ve gone there, my favorite thing about CHILDREN is that it’s actually a double plural.

KELLY: Yes.

DANIEL: It was CHILD and then… Oh, you know this one, Kelly. Go ahead. Hit me.

KELLY: Oh, no, please.

DANIEL: Am I getting it right?

KELLY: Yeah, you’re getting it very right.

DANIEL: CHILD and then CHILDER. Because that didn’t seem plural enough over time, it got childer-en.

KELLY: I like that.

DANIEL: So, if you hear somebody talk about the CHILLUNS…

KELLY: Chilluns.

DANIEL: …it’s a triple. Anyway, these two are not related. And the reason we know is because back in Old English, the way you did, third person singular wasn’t an S. It was with an -ETH, like “he speaketh” or “she doeth”.

KELLY: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: It was totally different. But this swapped to “he speaks” and she does by the 900s. However, -ETH stuck around for a long time in more informal writing. We can still see it in King James English in the 1600s. And in fact, a couple of episodes back, we mentioned there were a pair of linguists, Terttu Nevalainen and Helena Raumolin-Brunberg from the University of Helsinki. And they took a look at people’s correspondence, men’s letters and women’s letters. And they found that women are at the head of the change in things like changing from MINE and THINE to MY and THY.

KELLY: Cool.

DANIEL: And they were also at the head of the change where they said instead of “she speaketh” in formal writing, it was “she speaks.” Women were at the head of the chain.

KELLY: I love that. That’s really cool.

DANIEL: Yup. So, we find that those aren’t related. By the way, we found three things that the suffix -S does. But there’s another one.

HEDVIG: Oh.

DANIEL: Does anyone know? It’s my favorite.

HEDVIG: Wait, let me think. Give me a second.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Oh, is it just like clitic ‘S? Like, HE’S a linguist? No.

DANIEL: Ah, you know what? That’s a good point. That is a case where S comes in, like clitic ‘S, “he is” or “he has”. I hadn’t thought of that and that is a fourth one.

HEDVIG: Yeah. You get “he has” as well.

DANIEL: Yup.

HEDVIG: “He’s got a lot of opinions,” or whatever.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: The other one is the adverbial genitive. We talked about possessive genitive, but this one’s an -S to make adverbs out of things. We see this in pairs of words like toward and towards.

KELLY: Yes.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: There’s words with -WAYS, like SIDEWAYS and ALWAYS. We see it in -SIDE, like BESIDES. And then now — I’m just going to run down my list, because this is a mind-blowing list — PERHAPS, INDOORS, and OUTDOORS. It’s an adverb. It tells how you are going or where you’re going. Also, ONCE and TWICE.

HEDVIG: Oh, one, ONCE. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah, ONE and ONCE. TWO and TWICE. The word SINCE and also ELSE.

KELLY: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: The Ss on the end are adverbial genitive markers, which I love. It’s so fun.

KELLY: That’s really cool.

HEDVIG: I never thought about that. But it’s not that many items. It’s not super productive.

KELLY: It also means something though, because it is like pre-1066 in English. So, it’s something we held onto throughout our Normaning of the language, which is fascinating.

DANIEL: Because we have those two kinds of terms growing up together, sometimes we have social meaning. We put social meaning onto them, like saying AMID versus AMIDST, and AMONG versus AMONGST.

KELLY: That’s cool.

HEDVIG: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Okay. Here’s our last one. This one’s from Kate on Discord. “I’ve always wondered where the CHOP in CHOPSTICKS comes from. I’ve always found it an uncomfortable word since it feels like it might have racist undertones.” Okay. Any thoughts?

KELLY: Oh, that’s fair.

DANIEL: Have you noticed that? Do you feel that way or…?

KELLY: They’re distinctly not chopping implements, right?

HEDVIG: Right. I thought it was like chopping, like dividing.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Is that what you’re thinking too, Kelly?

KELLY: No, I’m saying I think there’s maybe something to this because they don’t chop, but you’re saying they do chop. [CHUCKLES]

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Well, you can do a lot of things with chopsticks.

KELLY: That’s true.

DANIEL: Do they chop or do they not?

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

HEDVIG: Well, I bought a bunch of Korean stainless steel chopsticks ages ago, and I use them for a lot of things, [DANIEL LAUGHS] like mixing anything, poking anything. Sometimes, you need a poking tool. Sometimes, I use them in pairs to pick things up. But if you have a slab of something that’s soft, like, I guess tofu or dough, you could use a chopstick to divide. But I’ve never thought about it. A very, very popular chain here in Sweden is ChopChop, which is general East Asian fast food. It’s very popular among all of my niblings. And it’s called ChopChop.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: I don’t know.

DANIEL: Well, I’m going to give you four choices.

HEDVIG: Okay. Right.

DANIEL: I made a guess without even knowing what the answer was. And then, my guess was one of these. Okay, here we go. Is it A, because they were actually used to chop things? B, is it a reference to CHOP, an inferior kind of food, like hash, I guess? Chop, an inferior kind of food. Number three or letter C, CHOP meant FAST, like chop-chop. And these sticks are associated with quick eating. Or, was it D, a racist taunt against the people who used them?

I’ll read them again. A, because they were used to cut things, they were used to chop. B, is it a reference to CHOP, an inferior kind of food? Did CHOP mean fast like chop-chop, and these sticks are associated with quick eating? Or, was it a racist taunt against the people who use them?

KELLY: I’m torn between B and C. I feel like…

HEDVIG: Yeah. Me too.

KELLY: …I want to know when this came into the language to be able to choose between them. But I’m going to go with fast, C.

DANIEL: Okay. Letter C. Very good.

HEDVIG: My instinct says C as well, like Kelly.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: I have two reasons for not choosing it. Last time I went with Kelly, I got it wrong.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

KELLY: Fair.

DANIEL: Yes.

KELLY: Yeah, I will mislead.

HEDVIG: Number two is, it sounds exactly the thing Daniel would make up. Like, it sounds like prime Daniel fantasy alternative. But that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

DANIEL: Don’t try to get into my head, man.

HEDVIG: No. I also think it’s fast. But I do like B as well. I think B is good. The last one that it is a racist taunt could be the case. I don’t know enough about it.

DANIEL: Okay. All right.

HEDVIG: I’m going to go with C.

DANIEL: Okay. My guess was B. I thought there was a term, CHOP meaning an inferior kind of like street food or something like that. I thought I remembered that from somewhere and that’s what I thought.

HEDVIG: That’s slop chop.

DANIEL: Yeah, that kind of… Like, hash. I voted B. You two voted C. The correct answer was C. You both got it.

KELLY: Amazing.

DANIEL: Yay.

KELLY: It’s not racist, y’all! [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: It’s not racist. Not exactly. There’s a Cantonese word, 急 gap1 which was “urgent”. It worked its way into pidgin English, CHOP, which meant quick. So, they’re quick sticks.

KELLY: That’s cool.

HEDVIG: That’s fun.

DANIEL: All right. Thank you so much to our listeners for giving us lots of great Related or Not words. We are having lots of fun with that. Let’s move on to our questions. This one’s from Diego on Discord. Diego says, “I know we use -ER in English for a few different things, like a person or a thing that does something, FIGHTER. Or, comparatives, COLDER or HOTTER. But what about other words like BITTER, AFTER, ALTER, TAMPER, RUBBER? Does the -ER in those words carry any meaning?” What do you think? It must do.

KELLY: RUBBER is the weird one for me in that list.

DANIEL: What do you reckon about RUBBER?

KELLY: Well, because…

DANIEL: [OLEAGINOUSLY] Because it rubs.

KELLY: Is it a brand name?

DANIEL: I don’t think it is.

KELLY: Rubber? It’s not like a Kleenex, like a proprietary eponym? If rubber is like a brand, and not just a natural product… I should know this.

DANIEL: It’s not. It just comes…

KELLY: It’s not. It’s produced. It just comes out of a tree?

DANIEL: So, it comes out of a tree. This is our first version of -ER. One who does a thing or a thing that does a thing. And it’s just rubber, a thing that rubs.

HEDVIG: Instrumental. Well, this is where I need to be the representative of not Americans. So, rubber is a material that comes out of a tree or whatever. It is the thing that you erase pencil marks with. And it is also a condom.

KELLY: A rubber.

DANIEL: Which causes no end of apocryphal confusion.

HEDVIG: Yeah. But they are all made out of the same material. But Daniel is saying that the -ER is like an instrumental. So, it’s like a tool to do a thing, and it is made out of rub. Or, it is rubbing and it is the thing that rubs.

DANIEL: That is correct.

KELLY: It is the thing that rubs.

DANIEL: It is the thing that rubs.

KELLY: Yeah.

HEDVIG: It’s the thing that rubs.

KELLY: Yeah. That one’s the one that feels odd in the list. Will you read the list again?

DANIEL: It was BITTER, AFTER, ALTER, TAMPER and RUBBER.

HEDVIG: I think ALTAR is the weird one, because “alta”, like back or something, right?

DANIEL: To change.

HEDVIG: No.

KELLY: Like the word, just alt?

HEDVIG: Doesn’t ALTA mean “behind” in Roman languages?

DANIEL: As a prefix?

HEDVIG: It’s like the back of the room, like in a church.

KELLY: Oh, like up at the front?

DANIEL: Yeah, we’ve got two different things. One is the altar, the big stone thing that you sacrifice…

KELLY: With an A.

DANIEL: …someone on with an A.

KELLY: Altar. Yes. And then you’ve got ALTER, to change, -ER.

KELLY: With an E.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s it. I think we’re talking about -ER. So, let’s put aside ALTAR with an AR and instead focus on alter with -ER.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: Because this is going to take us to our second kind of -ER. We’ve already covered the first one, which is, the one who does a thing like teacher, and RUBBER falls into this category. Then we’ve got the more, which is the comparative.

KELLY: Like warmer.

DANIEL: Yeah. And ALTER is in this category, because AL- means beyond. And if you make something al-ter, more beyond, then you’re changing it more. You are altering it. So, surprisingly, ALTER is this more meaning.

KELLY: Okay.

DANIEL: Another surprising thing is that AFTER is another one of these. If it’s aft, if it’s behind…

KELLY: That makes sense.

DANIEL: …then if it’s after, then it’s even more behind.

HEDVIG: But here we get again, this thing of like, we get the same problem as with the S, where a lot of different forms are reduced and made into S. And S then means a lot of different things that are etymologically unrelated.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: Now you’re telling me that you’ve got another one of these, that -ER is like instrumental or agent and also this more meaning. It’s like, why is English picking the same…? It’s suspicious.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Are they related or not?

HEDVIG: Right?

DANIEL: Yeah. Well, convergent, right?

HEDVIG: It’s just like, why? Why converge on those things?

DANIEL: Can I suggest that maybe the alveolar ridge could be the answer? Because when you have sounds, if you look at the ends of English words, we’re going to see some of the same sounds. We’re going to see S, we’re going to see N, like EATEN or DONE. We’re going to see -ER. What do those have in common? You always put your tongue near or on that space behind your teeth, the alveolar ridge. It’s like a really normal… Oh, and L, -AL. It’s a really normal way to end a word. Also, there are a lot of alveolars in English too. So, I guess it’s likely to have lots of them.

HEDVIG: Why does no other language I know do this, like so much with these ones?

DANIEL: I think a lot of languages do have a combination of suffixes that are very likely. Don’t you think?

KELLY: Sure. It’s just not like you’re saying in the same sound space.

HEDVIG: Yeah, why are they all S?

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

KELLY: Or, like all -ER, all Ns.

DANIEL: Yeah, you’re right. There are an awful lot of Rs and they have converged, I guess. Because when you start ending words that way, it seems likely for a lot of words to end that way. It’s like a magnet. It’s weird. I haven’t gotten to the other two meanings of -ER. One is…

HEDVIG: Oh, there’s a third one.

DANIEL: There’s four. Well, there’s three.

HEDVIG: Oh, god.

DANIEL: The third one is a verb suffix that means repeated or diminutive action. That’s from Etymonline. So, when you have a FLICK, that’s one thing, but a…

DANIEL and KELLY: FLICKER.

DANIEL: Yeah, is a bunch of stuff.

HEDVIG: Oh.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: Also, words like GLITTER. GLIT was evidently a thing. But then GLITTER, there’s a lot of them. And then, SLUMBER.

KELLY: There’s lots of these.

HEDVIG: GLIMMER, etc. Yeah.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. There’s a lot of them.

KELLY: Yeah. PITTER PATTER. There’s… a writing frequentatives is a big one. [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: I love frequentatives.

KELLY: Oh, yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

KELLY: A lot of them have -ER though, now that I’m thinking about it.

DANIEL: They do.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: And then we have some that are just accidents of history where there is epenthesis. There was just an R after a consonant and an E stuck itself in to make things a bit different. So, TEMPER, to control yourself, it comes from Old English TEMPRIAN. But once we got rid of the -IAN, something had to come between the P and the R. So, TEMPER it was. And BITTER as well. Proto-Germanic, BITRAS. Which is reminding me of R metathesis. That’s another one of my favorite things. Have we done a thing on R metathesis?

HEDVIG: BIRD / BRID, right?

DANIEL: Yup.

HEDVIG: It’s the only one I remember.

DANIEL: HORSE and HROS.

HEDVIG: Hros.

DANIEL: THIRTEEN used to be THRITEEN.

KELLY: COMFORTABLE? Does that one count?

DANIEL: Yes, that is a perfect example, because it’s COMFORTABLE, RT. But when we say it, it’s comfort-able. [DANIEL MEANT TO SAY COMF-TR-BLE]

KELLY: Fortable.

DANIEL: We swap the TR.

KELLY: Yeah.

DANIEL: Comfortable. Some people say MOD-REN instead of MODERN.

KELLY: Oh, yeah.

HEDVIG: Oh, I love that.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: My brother and me, they always say we’re an advice show for the mod-ren era and I love it every time.

DANIEL: And then there’s the one that blew my mind this week. The name of Oprah Winfrey. The name she was born with was not Oprah. It was Orpah. Orpah is a biblical name. I remember reading that, because I’ve read the Old Testament twice and I found that name and I thought, “Did that just say Op…?” Oh, no, it didn’t say Oprah. It was Orpah. Her birthname is Orpah. But so many people, because of R metathesis, flipped it.

KELLY: That’s fascinating.

DANIEL: So, it’s stuck.

KELLY: Now she’s Oprah.

DANIEL: And now she’s Oprah. There we have it. ER, the er has come to us a lot of different ways and it’s a super weird example of convergence. Thanks, Diego, for that question. I think I want to jump to a comment. This is from Adam via email. It’s about BLUE CARD. Do we know what a blue card is? Ben and I didn’t.

HEDVIG: I learned about it yesterday at a party. Someone was explaining it to me, because I am an involuntary WAG, which is a British term for “wives and girlfriends”, which is the women who are associated with their men who play football. It is a football term. So, I am married to a man who really likes football. And in an attempt at getting to know my husband better, I’ve tried to understand football. I think that sometimes very good football is a bit boring, because they’re all too good at it and nothing happens. They need a smaller field, fewer people. More balls is my thing that I’ve been trying to convince a lot of British people about. Like, they should have two balls at one time.

But every now and then, they talk about rule changes. There’s been a couple of important rule changes in the last couple of decennia, and one of them is that…

KELLY: There’s a blue card.

DANIEL and HEDVIG: There’s a blue card.

HEDVIG: It’s between yellow and red. So, blue is you get sent off the field for like a certain amount of minutes, but then you get to come back.

KELLY: That’s really funny.

HEDVIG: It’s also funny, because it should totally be orange because it’s between yellow and red.

KELLY: Right.

DANIEL: Too hard to see.

HEDVIG: But apparently, it’s been borrowed from some American sport, a guy at a party told me last night.

DANIEL: Wow.

HEDVIG: Is that true?

DANIEL: Let me read Adam’s thing. “Hello, Because Language crew, I just finished listening to the latest episode, Episode 92. And as an avid football soccer fan, I’d like to try to provide clarity on the blue card Word of the Week discussion. A yellow card is given for a cynical foul, dissent towards the official, or what is called a professional foul, a foul to prevent or stop an attack by the opposition. Two yellow cards in a game equal a red card, but also an accumulation of multiple yellow cards in different matches can lead to a suspension.” Okay, I’m going to go on to the red card.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: “A red card is for a dangerous foul hitting an opponent, or a foul that is deemed as the denial of a goal-scoring opportunity. You get a suspension for at least the next match and possibly more. A blue card would be a penalty between a yellow card and a red card, just as you said, Hedvig. It would be a borderline yellow or red foul or dissent. The biggest difference with this card would be the penalty of 10 minutes in the sin bin.” That sounds like another Word of the Week. I like SIN BIN.

KELLY: SIN BIN.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: “A player would be sent off the pitch for 10 minutes and their team would be forced to play with one less player for those 10 minutes, but not the rest of the match. As with a red card, most other fans are not happy with this proposed change, which will only be taking place at lower levels. It appears to be aimed at curbing the abuse of officials that is seemingly happening more frequently.” Adam says, “Hope this helps. Love the show. As a fellow ex-Mormon in Utah, I particularly enjoy when the topic of Daniel being an ex-Mormon comes up, and I can relate so deeply with it, Adam.” I’ve got to say, I think we’ve got the linguist/ex-Mormon thing locked up. So, that’s nice.

HEDVIG: I know another ex-Mormon linguist that we can have on the show, if you want.

KELLY: Me too, actually.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

KELLY: There you go.

DANIEL: There’s a bunch of us. There’s a lot of Mormon linguists as well, and we are interested in hearing from you too. So, thank you. I’d like to keep it so that when there’s somebody who’s struggling with a transition out of their faith, I like to be the one who’s there saying, “You can do this.” So, if you’re a Mormon and you’re happy with it and there’s been informed consent, you know everything you need to know about the church, then go for it. Follow your bliss. If you’re an ex-Mormon, that’s great too. Come on and hang out with us. We love it. And thanks to Adam for that email.

HEDVIG: I am just an exotifying old-timey anthropologist bystander. I am just fascinated by Mormon ideology. And every time I hear something new, I’m like, “There’s a planet where God lives?” And like… No, sorry, there’s a star where God lives. “And when I die, I get a planet?” That sounds amazing. I think it’s really fun. It’s like my Hunger Games.

KELLY: [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: Well, I will go on for hours and hours if you would like. Well, I feel like we fixed a lot of things around here today. We’ve answered a lot of questions, taken some comments. So, I just like to say thank you to you, Dr Kelly Wright. How can people find out what you’re doing?

KELLY: Oh, thanks. Yeah, I am easily googleable. “Kelly Wright linguist” will get you there. I’ve got a website and an inactive Twitter account. People can absolutely email me, find me on YouTube.

DANIEL: Are you the most famous Kelly Wright on the internet?

KELLY: That’s a good question. No. [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

KELLY: There’s… a Kelly Wright runs the NOAAD, the North American Atlantic Aeronautical whatever.

DANIEL: Oh. Wow. Okay.

HEDVIG: Yeah, department. I don’t know. And then, there’s like a Fox News anchor of the same name, a Black guy.

DANIEL: Yeah. Okay. All right.

HEDVIG: He usually comes up first. But anyway. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Thanks also to the team from SpeechDocs who transcribes all the words. And thanks to patrons like you who make the whole show happen.

[MUSIC]

HEDVIG: You can support Because Language. And if you are listening to this, you are probably already supporting it, because this is a Patreon episode that goes out to Patreon supporters first. But later, it goes out to non-Patreon supporters as well. And if you would like to hear this episode earlier than you now did, or if you would like in general to support us because you like us and you would like us to keep going, you can tell a friend about us or leave us a review. We like reviews. You can leave them in many places. I think my favorite one is Podchaser, because it’s not Apple only, but you can leave on Apple as well. That’s all right. We’ll read it. You can also follow us. We are becauselangpod on all the social places that you might want to be on. You can also send us ideas or comments, especially Related or Not. Examples is really fun when we get from listeners.

DANIEL: So many.

HEDVIG: You can email us those and they are at hello@becauselanguage.com. That is our email. It is one of the best places. You can also message us on Facebook and wherever else, but the email is a surefire way to get it straight to us.

You are also very welcome to send us your voice. If you do have a question for us and you would like us to play your voice asking that question, we are very welcoming of that. You can just either go to SpeakPipe on our website, becauselanguage.com, or you can just record yourself a little voice memo and then just attach it to a file and then just send it. All of those things are very welcome. We love when you talk to us.

DANIEL: We also love it when people become patrons. Your support means that everyone gets to have episodes for free. The regular episodes. Means we can get transcripts from SpeechDocs, and it means that we can share the love and send some money to our guests. Because if we only hear from people who can afford to work for free, then we only hear from some people those who are already doing well. We need to hear from a range of voices.

If you’re a patron, you get bonuses depending on your level, like Discord access, mailouts, shoutouts, live episodes, bonus episodes, shoutouts like this one. I’d like to read out our patrons at the supporter level. There’s a big list. We got a lot of new supporters this time, which is super, super good. Here they are.

Termy, Elías, Matt, Whitney, Helen, Jack, PharaohKatt, LordMortis, Elías, gramaryen, Larry, Rene, Kristofer, Andy B, James, Nigel, Meredith, Kate, Nasrin, Joanna, Nikoli, Keith, Ayesha, Steele, Margareth, Manú, Diego, Ariaflame, Rodger, Rhian, Colleen, Ignacio, Sonic Snejhog, Kevin, Andy from Logophilius, Stan, Kathy, Rach /ɹaʃ/, Cheyenne, Felicity, Amir, Canny Archer, O Tim, Alyssa, Chris, aengryballs, Tadhg, Luis, Raina, Tony, WolfDog. [HOWLS] And our new supporters this time, Molly Dee. sæ̃m, who just sent us a super nice email. Sam, thank you for telling us about how you feel about the show. Also, j0hntr0y with a yearly subscription…

KELLY: [APPLAUSE]