We’ve got mail, and linguistic MVP Dr Nicole Holliday is here to help us sort some things out around here. And we chat about the state of lingcomm today.

- Why is dog sushi made for dogs, but duck sushi is made from ducks?

- What do we call it generally when companies try to improve their image by –washing?

- Is the term MVP becoming uncoupled from sports?

- Will vaping kill your vocal fry?

- Are shibboleths made on purpose, as a way of creating an in-group and an out-group?

Plus our favourite game: Related or Not!

Listen to this episode

Video promo

Patreon supporters

Huge thanks to all our great patrons! Your support means a lot to us. Special thanks to:

- Iztin

- Termy

- Elías

- Matt

- Whitney

- Helen

- Jack

- PharaohKatt

- LordMortis

- gramaryen

- Larry

- Rene — who has been a patron since 2019, but made the decision to bump up to the Supporter level

- Kristofer

- Andy

- James

- Nigel

- Meredith

- Kate

- Nasrin

- Joanna

- Nikoli

- Keith

- Ayesha

- Steele

- Margareth

- Manú

- Rodger

- Rhian

- Colleen

- Ignacio

- Kevin

- Jeff

- Andy from Logophilius

- Stan

- Kathy

- /ɹaʃ/

- Cheyenne

- Felicity

- Amir

- Canny Archer

- O Tim

- Alyssa

- Chris

- Laurie

- aengry balls

- Tadhg

- Luis

- And new this time: Raina!

And our newest patrons at the Listener level: Kim

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

Complex Variation in the Construction of a Sociolinguistic Persona: The Case of Vice President Kamala Harris

https://read.dukeupress.edu/american-speech/article-abstract/doi/10.1215/00031283-10867240/382797/Complex-Variation-in-the-Construction-of-a?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Zoom launches an AI companion and introduces AI-heavy Zoom Revenue Accelerator

https://siliconangle.com/2023/09/06/zoom-launches-ai-companion-introduces-ai-heavy-zoom-revenue-accelerator/

Amazon’s new health band is the most invasive tech we’ve ever tested

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/12/10/amazon-halo-band-review/

Spectacular Vernacular with Nicole Holliday and Ben Zimmer

https://slate.com/podcasts/spectacular-vernacular

Beth Levin, Lelia Glass and Dan Jurafsky. (2019). Systematicity in the semantics of noun compounds: The role of artifacts vs. natural kinds

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333147338_Systematicity_in_the_semantics_of_noun_compounds_The_role_of_artifacts_vs_natural_kinds

Spanish Compound Nouns

https://lightonspanish.com/spanish-compound-nouns/

paracaidas etymology

https://etimologias.dechile.net/?paracai.das

Greenwashing and pinkwashing | Grammarphobia

https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2022/01/greenwashing-pinkwashing.html

A‑Z of social movement and greenwashing

https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/social-movement-greenwashing

The Laundry list (of sustainability washing)

https://www.bemari.co.uk/blog/the-laundry-list-of-sustainability-washing

It’s a trap; how to beware of greenwashing, pinkwashing and bluewashing | Medium

https://ccrave.medium.com/its-a-trap-how-to-beware-of-greenwashing-pinkwashing-and-bluewashing-b71badebb82b

Kevin Durant MVP Speech | Know Your Meme

https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/events/kevin-durant-mvp-speech

Kevin Durant Reveals His Thoughts on the ‘You the Real MVP’ Meme

https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2369256-kevin-durant-reveals-his-thoughts-on-the-you-the-real-mvp-meme

At 77, MVP has not stopped dreaming of a better future for all

https://www.philstar.com/business/2023/07/14/2280854/77-mvp-has-not-stopped-dreaming-better-future-all

The PIN-PEN Merger | Ace Linguist

https://www.acelinguist.com/2020/01/the-pin-pen-merger.html

The Effects of Vaping on the Voice | Sarp Kurtoglu of the Osborne Head and Neck Institute

https://www.ohniww.org/the-effects-of-vaping-on-the-voice/

Indexical borders: the sociolinguistic scales of the shibboleth

https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/ijsl-2020-0095/html?lang=en

Judges 12:6

https://www.bibleref.com/Judges/12/Judges-12-6.html

Don’t You Dare Use ‘Comprised Of’ On Wikipedia: One Editor Will Take It Out

https://www.npr.org/2015/03/12/392568604/dont-you-dare-use-comprised-of-on-wikipedia-one-editor-will-take-it-out

Teens Love LinkedIn

To some high-schoolers burned out on FOMO and thirst traps, the networking platform is “the way social media should be.”

https://www.thecut.com/article/why-teenagers-love-linkedin.html

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

DANIEL: I put this one to our listeners on Discord. I asked if they had any questions for Nicole. And aengryballs on our Discord has asked a question for you.

NICOLE: Okay.

DANIEL: “Would you rather eat chocolate or updog?”

NICOLE: Updog?

DANIEL: Yeah. Would you rather eat chocolate or updog?

NICOLE: Chocolate. [LAUGHS] I think chocolate. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES] Would you not like to know what updog is? And pose a question to that effect?

NICOLE: [LAUGHS] It feels safer, but yes. What is updog? Now that I have been prompted to ask. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Not much. What’s up with you?

NICOLE: Nooooooooooooooo.

DANIEL: Tell me that’s not the first time you’ve heard that joke!

NICOLE: I mean, I think it might be.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Hey, aengry balls, you got somebody. Oh, my gosh.

NICOLE: Ah, good for them. [LAUGHS]

[PAUSE]

DANIEL: I’m sorry.

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

DANIEL: Hello, and welcome to this very special bonus episode of Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. My name is Daniel Midgley, and with me now, a great public linguist, a fun guest, and our honorary cohost, Dr Nicole Holliday of Pomona College. Nicole, thanks for coming on the show.

NICOLE: Thanks, Daniel. It’s been too long. I feel like I have to talk to y’all at least every two years just to keep my honorary cohost status.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Don’t worry. It’s not in jeopardy at all. But yeah, it has been a while. We talked to you about in the episode, Madame VP, about your work in the sociolinguistics of Kamala Harris’ recordings and voice and performance. What have you been doing lately?

NICOLE: Thanks for reminding me that that’s what we discussed last time. I didn’t go back and listen because it’s hard to listen to yourself. That paper is actually now online. It’s out in the advanced section of American Speech. In case anybody wants to read my thoughts about Kamala Harris in a more scholarly forum or formal forum, I would say that we’re scholarly here. So, I’ve been very interested in this thing that I’ve started to call Social Feedback Speech Technology. So, during the pandemic, when we couldn’t talk to humans, I was like, “Ah, I guess we got to talk to computers.” So, a lot of people started doing a little bit of research in the tech space, which was not something that I thought I would ever do. But it turns out that there are a lot of speech techs now that are trying to tell you something about how you sound to others. So, in fact, we’re on Zoom, and when we first hopped on this Zoom, I got a pop up that was like, “Improve your meeting with the power of AI.” And I know that Zoom has just introduced this thing called the Zoom Revenue Accelerator.

DANIEL: Yes.

NICOLE: Yeah, it sounds terrible, right?

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: What? Can’t we just talk?

NICOLE: No, no. We must accelerate our revenue. It’s marketed to businesses, and they say things like, “Oh, yeah, you should see if you’re talking too much,” or, “If your client is asking questions versus statements. And this is going to help you better understand how it’s working.” And it does some sort of gross feedback about whether you sound agreeable and that kind of stuff. I haven’t gotten to try it out yet because it’s literally hot off the press, but I’m interested in that kind of thing. And I have a presentation at the Linguistic Society of America in January actually with Paul Reed from the University of Alabama. We are competing in the 5-Minute Linguist for a research in this space on a device called the Amazon Halo.

DANIEL: Okay.

NICOLE: Have you heard of it?

DANIEL: No.

NICOLE: Yeah, they just continued it because no one bought it. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Not everything works.

NICOLE: No, not everything works. I guess this is good for our purposes because we’re arguing that it’s a little nefarious, but it’s basically a Fitbit type fitness tracker device thing that has this special feature called Tone of Voice, the tone feature. And it gives you a score for energy and a score for positivity. And in the research, we found, that shocking, it’s racist and sexist.

DANIEL: What?

NICOLE: [LAUGHS] Who could have imagined?

DANIEL: In AI? But I thought the algorithm was neutral. I’ve been tricked.

NICOLE: Yeah. So, it’s systematically biased against the women and the black folks in our study. We have them all reading the same passage, so it’s not something about the content at all, but it doesn’t like them. So, this makes me anxious.

DANIEL: Ugh. Yeah. I’ve often thought… Ugh, this is why I’m not making any money, because I’m not loading up my language performance with positivity and energy. I must sound like some kind of pushover. And then I just think, is this the new prescriptivism? Is this going to load people up with horrible, stupid advice?

NICOLE: Yes, it is. And the horrible, stupid advice is particularly evil because it preys on people’s preexisting linguistic insecurities. So, the fact that it’s got this gender bias is very obvious. Women are often policed for their language, so who’s going to be concerned that they don’t sound sufficiently positive? People that are already policed, same thing with people of color. And it’s ignoring a lot of things about the way that variation works. So, for one thing, it’s only listening to you, So, it can’t tell you how positive you sound to any given interlocutor, audience, whatever. It only knows what you’re doing, and it doesn’t have any idea of the other contextual factors that could influence someone else’s perception of you sounding energetic or positive. Finally, it also doesn’t make sense to always sound positive. If you’re delivering bad news, you don’t want to be like, “Oh, so well, your dog is not in great health.” That’s bad.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Toxic positivity.

NICOLE: Yeah. So, I hate this. I don’t think that the technology is at a place where we can do this effectively. And I do think it’s a recipe for sort of widespread prescriptivism, especially because people are really sort of impressed by the power of AI and see it as neutral.

DANIEL: Yeah, Yeah.

NICOLE: But it’s not. It’s based on its own training data, and its training data is not neutral because we’re not neutral, as you all discussed in your episode that had Dr Emily Bender, which was awesome.

DANIEL: Thank you.

NICOLE: I’ve been doing that.

DANIEL: Okay. Wow. It sounds fascinating. And I think we’re going to need to keep track of this issue because AI, being the shiny thing, is going to get picked up and utilised because it’s popular. But it’s not giving neutral advice and if it’s just cranking out bad advice that people already kind of believe, this is a recipe for disaster.

NICOLE: Pretty much. And it’s a recipe to sort of discriminate against people by distancing yourself from it. So, you can imagine a situation in which some kind of commission based, like your realtor, something like that, gets fired because, “Oh, well, the AI says that you’re not effective enough.”

DANIEL: Yeah. It speaks to deprofessionalisation. Let’s trust each other to be good users of language in situations. Maybe we’re not optimal, but we’re not robots. And if we’re taking advice from robots to become optimal, that’s not human. That’s not good.

NICOLE: It’s not human. And also, in particular, a lot of the stuff that we’ve discussed around ChatGPT or whatever has been about text. But the voice is much, much more complicated for AI to process. First of all, it’s just a lot more data. So, it’s really algorithmically expensive to process speech data in a way that it’s not as much with text. And we already have problems with text. ChatGPT is really, really computationally expensive. And then on top of that, you just have like human factors. So, if I have a cold for three weeks, is it going to start to say I don’t sound positive? We live in bodies. They vary.

DANIEL: Yeah. And these things happen situationally. And every situation is going to be slightly different. So, saying, “According to our model, you sound not very energetic,” well, these things happen in a situation, and that’s not the situation.

NICOLE: Yeah.

DANIEL: Ah, weird. Okay.

NICOLE: They’re keeping us in business, I guess, with all of this kind of stuff.

DANIEL: Because then we can talk about it. And so that kind of leads me to the next thing I wanted to ask you, because I loved Spectacular Vernacular while that was a thing. So good with you and Ben Zimmer, so much fun. What’s the state of public linguistics today as you see it? Are we in good times? Is it Golden Age? Is it rough? What’s happening on the scene for you?

NICOLE: I think there’s a lot of content. There was a joke for a while there that everybody and their brother had a podcast, and there are a lot of podcasts where it’s just like people hanging out with their friends, and they got 10 listeners. And that’s fine, right?

DANIEL: Yeah, right. Duh.

NICOLE: It’s a hobby like anything else. Great. Do it. Fine. I think that it’s very difficult to have something that is scholarly and well researched and also entertaining the way that you all do, or what we tried to do on Spectacular Vernacular. Ultimately, what we were told was that they couldn’t figure out how to sell ads to keep the show running because our podcast didn’t have a clear, defined audience. It wasn’t like, “Oh, it’s women under 25,” or, “It’s people in the Midwest over 60,” or whatever the ad revenue predictions say. So, that is a bummer.

But there are a lot of people doing these podcasts, like you all, like Vocal Fries, like Lingthusiasm as sort of a labor of love and being listener supported. So, I’m glad that those continue at least. And the linguists who teach love that you all keep doing this because it gives us places to send students. We use them in assignments. So, it’s staying alive through the pedagogy at least.

DANIEL: That’s good. Well, in that case, let me ask, I mean, would it ever be possible for a good linguistics podcast to be huge? What’s the ceiling for a good linguistics podcast? Do you know what I mean?

NICOLE: Yeah, I mean, I think we’re a little bit wonky. Whenever you’re talking about a topic that’s kind of academic, you’re going to lose some people. So, thinking about the biggest podcasts of all time, like Serial or anything like that, everybody is interested in crime.

DANIEL: I guess.

NICOLE: [CROSSTALK] …no feeling to crime. But I do think that there’s a space for it. And when we were doing Spectacular Vernacular, it was picked up by Slate, which is a major American sort of journalist… I mean, that’s who was paying us, and it was great. I think that there was a little bit of an issue of the timing and also the marketing. And so, I would love if a podcast like that, maybe not with us, but podcasts like that got picked up by a major podcast distributor. And Ben and I have talked about, “Can we do a revival? Can we pitch it?” But it’s actually a little bit of a lean moment for journalism in the United States. It’s been true forever, so I don’t know if we’ll be able to bring it back, but I think that we might get there some day.

DANIEL: I just feel like in order for a linguistics podcast to be huge, it would have to become trash, or it would have to do… not do bad things, but it would have to be entertaining. And science isn’t always entertaining. Like, what we do is fun, but we try to bring our personalities, and that’s the entertaining bit. But what would it even look like if it was massive?

NICOLE: Yeah. So, what we did when we had Spectacular Vernacular that I thought was great was, Ben, in addition to being a lexicographer and sort of language journalist, is a puzzle person. So, we always had a game, and people love…

DANIEL: I love the game.

NICOLE: …the games. Yeah, the game and the puzzle. I’m not as much of a puzzle person, so I learned a lot about puzzling, but that’s pretty engaging. And there are always sort of language games and language twists. And we also tried to talk about current events in the same way that you all do sometimes. Grab something from the news and discuss the language angle on it. So, that makes it a little bit more relatable to a broader audience. But people have limited hours in their day, all of us, [CHUCKLES] and I personally have too many podcasts. Like, every time I learn about a new podcast, it’s a little bit bittersweet because I’m like, “That sounds great. When?” Because I’m already on like six hours of podcasts per day in my ears. There’s no more space. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: “I’ve been at the gym every day for three hours this week. What can I do? I don’t drive that much.”

NICOLE: Yeah, “My dog is being overwalked because I just keep listening to podcasts.”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

NICOLE: Something like that.

DANIEL: Well, I would love to see a revival of Spectacular Vernacular. You guys did a great show. It was really fun. You had cool guests. The puzzles were fun. I loved the current issues. Let’s see what we can do. Let’s keep doing crossovers for now.

NICOLE: Yeah, would love to.

DANIEL: Okay, great. Well, what’s coming up today, Nicole, is we’re going to be tackling the mailbag. I brought you in so that you can help me get through our voluminous listener mail. There are some great and strange questions. What do you think?

NICOLE: Okay, I hope I know. I am a specialist in my area of linguistics, and you all take a really broad set of questions. So hopefully, it’s something that I have some clue that I can speak on intelligently. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: We will do our best. Hey, if you are listening now, you are a patron, so thanks for supporting the show. You make the show work. You help us compensate ourselves and our guests and helpers for the work that we do in making the show. You also make it possible for everyone to hear regular episodes. So, thank you for being there. Every month, we gain some new patrons, but we lose some others. We’re really grateful for all of you who stick with us month after month and also for those of you who make your subscription yearly, which is now a thing you can do, and I think you can save some money doing that.

A bit of housekeeping for all you patrons. Our annual mailout is coming with stickers and magnets and postcards and things. If you want it, I need you to update your address in Patreon so that I’ll know where to send it. Otherwise, I just won’t know or tell me somehow. Email me, hello@becauselanguage.com. And if you’re listening to this a little bit later and you’re not a patron, please consider becoming so you’ll be helping the show. So that’s patreon.com/becauselangpod.

All right, enough of that. Let’s get to the questions. This one’s from Wolf, who says, “Hey there, longtime listener, second time caller.” Hey, I will get to your sign language question, Wolf. It’s just we need to bring in some help. Oh, and notice to everybody else, sign language questions? Send them, we’ll do a full show. Wolf says, “My brother has recently told me about what he calls the dog sushi problem, and I thought it might be worth sharing. Dog sushi is an example that he uses in his,” uh-oh, “UX, user interface.”

NICOLE: User experience?

DANIEL: Okay, very good. User experience. Thank you. Design work. I should know these. “For how when there’s two nouns strung together, there isn’t always one simple and consistent rule for parsing that. The specific example is that he once brought… bought some dog treats labeled…” I just mixed up, bought and brought. Did you catch how I did that?

NICOLE: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Goodness gracious. This is the one thing that people complain about. “That he once bought some dog treats labeled ‘dog sushi’ made of some kind of treat, rolled around another kind of treat so it looks like cute little sushis for dogs. But then sometime later, he bought a bag of the same kinds of treats by a different brand but were instead labeled on the package as ‘duck sushi.’ And so one might conclude, if there were indeed a consistent rule, that obviously either the duck sushi treats are meant to be given to ducks, or conversely, that dog sushi treats are made of dog meat, neither of which is true. Do linguists have a name for this phenomenon? How does this work in other languages that aren’t English? Are there any other interesting things that linguists can tell us about this? Thanks for all the podcasting. Wolf.”

Thanks, Wolf. Whenever I reach a problem like this, I always raise my fist and I shout, “Curse you, English, and your ambiguous head modifier relations.”

NICOLE: Yeah, this is a sort of semantic structural ambiguity, I think, brought to us by the fact that English loves to noun verbs, noun adjectives, noun everything, and vice versa. Right?

DANIEL: Yeah, exactly.

NICOLE: What’s happening, I think, is dog, is dog modifying sushi, or is dog sort of underneath sushi to say that the sushi is composed of dogs, [CHUCKLES] thus the duck sushi problem. So, there’s a double reading because it’s not clear what the head noun is. English, with its eight million prepositions, can disambiguate this by putting it into a prepositional phrase.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s right.

NICOLE: but other languages that don’t sort of have this paradigm where everything can be like any part of speech, and also there’s a million prepositions, just don’t have structures like this. I can’t imagine this happening in languages with a very different morphology, but you can imagine it is like sushi for dog or sushi from dog.

DANIEL: Sushi of dog.

NICOLE: Of dog.

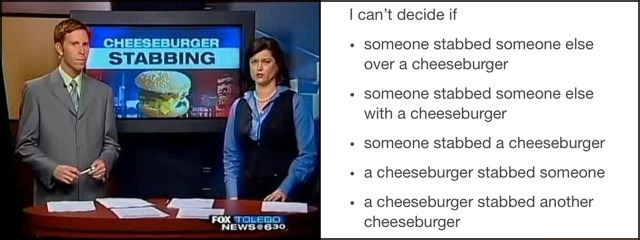

DANIEL: Yeah. I was thinking of lipstick, which in English is you just put lip next to stick. It’s not made of lips, it’s made for lips. But in French, you’ve got rouge à lèvres, and the à is sort of an indicator that’s the purpose. Yeah, my favorite example is there’s a meme, it’s got some newsreaders. And the thing that they’re referencing, it just has two words on the screen, “Cheeseburger Stabbing,” [NICOLE CHUCKLES] and the memer writes, “I can’t decide if someone stabbed someone else over a cheeseburger. Someone stabbed someone else with a cheeseburger. Someone stabbed a cheeseburger. A cheeseburger stabbed someone. A cheeseburger stabbed another cheeseburger.”

NICOLE: Yeah, I mean, we frequently see these with sort of longer… these are like linguistics 101 problem with a structural ambiguity. So, the woman saw the man with the binoculars. Who was holding the binoculars?

DANIEL: Structural ambiguity.

NICOLE: Yeah. But these noun ones are kind of more fun because they seem a little weirder.

DANIEL: They do.

NICOLE: I think that the people that made the dog sushi were relying on some social knowledge, actually some sociolinguistic competence…

DANIEL: That’s it.

NICOLE: …which is that we don’t hear eat dogs typically.

DANIEL: That’s it.

NICOLE: So, there’s only one possible interpretation that’s like socially appropriate here. But the duck sushi one… [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Duck sushi, I’ve never eaten a duck either, but I’d be more likely to eat duck sushi than dog sushi…

NICOLE: Yes.

DANIEL: …to be honest, in a compositional way. I also saw another one, fudge lantern. An online shop showed a reference to a fudge lantern. I have no idea what it is. Fudge lantern. But it was useful because in a post, someone was able to coin the expression, “You complete and utter-“

NICOLE: Fudge lantern. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] “-fudge lantern.”

NICOLE: Yeah. It does sound like sort of a non-insult, right?

DANIEL: It does. But also, you cringed a bit as though you were thinking of something unpleasant, and I don’t want to investigate that.

NICOLE: It sounds like an insult.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: You fudge lantern. It’s almost like when you place two words next to each other, you get an unusual chemical reaction.

NICOLE: Yeah.

DANIEL: Well, I wanted to know if somebody had made a contribution to the research. So, I found an article on ResearchGate, which is surprisingly not some kind of scandal about research. See what I mean?

NICOLE: Those nouns again.

DANIEL: Curse you, English. So, this one is an article by Beth Levin, legendary, and Dan Jurafsky, again, legendary. And Dr Lelia Glass, probably a legend, but someone I’m not as aware of. The paper, it’s on our website, the show notes for this episode. “Systematicity in the semantics of noun compounds: The role of artifacts vs. natural kinds.” All right, provocative.

NICOLE: Yes. I’m intrigued.

DANIEL: So, they list a number of possible relations. There’s color, like green bean. There’s location, like kitchen scissors. There’s made of, like our duck sushi. There’s purpose, which I guess is kind of like our dog sushi. I think that’s the relation that’s happening here. Oh, no, wait. No, sorry. It’s the other one. Used by, like Cowboy Cookies or navy beans. So, our dog sushi would definitely be in the used by. And they say, “We argue that the type of head modifier relation in an English endocentric noun-headed compound,” like we’ve been talking about, “depends on how its referent is categorised specifically on whether the referent is conceptualised as an artifact made by humans for a purpose, or as a natural kind existing independently of humans.” In other words, if it’s a thing we make, then that’s one thing, and if it’s a thing that we don’t make, that sort of just exists out in the wild, then it’s going to act a little bit differently.

NICOLE: So, we make sushi, but we don’t make dogs or ducks.

DANIEL: I know it doesn’t really help us because ducks and dogs are not artifacts, but I think if I had to put dogs and ducks on a sliding scale, dogs would be a little more, I don’t know, human adjacent, a little more artifacty. I don’t know. But anyway, let me get to their study, because they did a test, and I want to give you this test, Nicole.

NICOLE: Okay. Hopefully, I don’t embarrass linguists. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: No, no. You know as well as I do that your instincts are sufficient. Now, I’m going to get you to do a two-word compound for this thing. The question is, you subscribe to a service that sends you new food types every month. This month you receive a new type of chickpea. It comes from Istanbul. It’s green in color. You use it to make hummus. That’s the attributes. Comes from Istanbul, green in color, use it to make hummus. I want you to generate a two-word expression to describe this new kind of chickpea.

NICOLE: There’s so many. Turkish chickpea. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: It could be a Turkish chickpea. Yes, it could.

NICOLE: Yeah. And that could actually imply the other information if you had some knowledge of the world.

DANIEL: The hummus.

NICOLE: Yeah, like the hummus. This is not true, but imagine we live in a world where all of the chickpeas that come from Turkey are green, and their primary use is hummus. Then, would you say it’s a Turkish chickpea. I know, oh, it’s the green one that you use in hummus.

DANIEL: Yeah. Okay. Sounds good. So, you decided to go for place of origin.

NICOLE: Yes.

DANIEL: Okay. So, what they found was that’s what most people did. Because the chickpea is a natural object, it tends to attract names that talk about either its appearance or place of origin. People either called it a green chickpea or a Turkish chickpea. Just about nobody referenced the use, like a hummus chickpea or something like that. Let’s try the next one. You subscribe to a service that sends you new household tools every month. This month you receive a new type of spoon. It comes from Berlin. It is blue in color. You use it to mold cookies. What two-word name would you give to this new tool? And it’s okay to go a bit nuts here?

NICOLE: No, it’s a cookie spoon.

DANIEL: It’s a cookie spoon.

NICOLE: It’s not a German spoon.

DANIEL: And it’s not a Berlin spoon.

NICOLE: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Why would it be a German spoon? Like the Turkish chickpea.

NICOLE: Well, maybe it’s because it just doesn’t matter.

DANIEL: Yeah. What matters is what you do with it, because it’s an artifact.

NICOLE: Yeah, but with the chickpea, that’s a different thing, right?

DANIEL: Yep, that’s what they found. The spoon is an artifice, so it attracts words that describe its use, and that’s what we see. Cookie molder or cookie spoon. People were much less likely to call it a Berlin spoon or a blue spoon.

NICOLE: I don’t know. I had another thought here. I don’t know if they mentioned it in the paper, or maybe this is just another thing, but spoon is a really high-frequency noun, and chickpea is not. And before you gave me the spoon example, I was thinking about brush, which has a lot of noun modifiers. So, you can have a kitchen brush, you can have a toothbrush, you can have a hairbrush.

DANIEL: Oh, yeah. A nail brush.

NICOLE: Yeah, nail brush, a tire brush. They’re all the same kind of thing. They have the same function, but for different items that they attach to or different places. I guess kitchen brush is like, broadly, you use it to brush various things in the kitchen.

DANIEL: That was our place modifier. Yeah, the place relation. Okay, so the final word for this paper is, “When the novel object is an artifact, the compound’s modifier tends to reference its use. When it is a natural kind, the modifier tends to reference the object’s appearance or place of origin.” Then, they went through loads and loads of examples and found that was so. Now, turning back to our dog and duck sushi, humans didn’t make dogs or ducks, but dogs are more tightly aligned with humans. So, dogs use the sushi, but ducks are in the sushi.

NICOLE: Yeah, that makes sense. Our dogs, ourselves, right?

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Exactly. I like the way they do it in Spanish. Is Spanish one of your languages?

NICOLE: It is one of my languages, yeah.

DANIEL: So, they do it different. In English, we would say that someone is a kidnapper, but in Spanish?

NICOLE: Oh, okay.

DANIEL: Oh, not one of your items.

NICOLE: [LAUGHS] You know what? I don’t know crime words in Spanish.

DANIEL: You didn’t listen to those podcasts? Okay, cool. It’s a robachicos. It’s steal kids.

NICOLE: Oh, steal kids. Yeah. Oh, I was thinking, I looked real quick. Secuestradora. Sequesterer. [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: Oh, right. Oh, really? You just looked up kidnapper.

NICOLE: [CROSSTALK] -we do that. Yeah.

DANIEL: Oh, okay. I didn’t realise. So, in English, it’s going to be a noun verber. Like, if you got a thing that grabs snakes, it’s a snake grabber. But in Spanish, it’d be more like a grab snakes, typically.

NICOLE: Or what we get… when I remember like Spanish 1 or something, learning about parasol.

DANIEL: Yes.

NICOLE: It’s an umbrella. It is PARA — for — sol, sun. It is a for-sun. That’s awesome. Right?

DANIEL: I heard another etymology of that, that the PARA is not FOR.

NICOLE: What is it?

DANIEL: It’s “stops”, PARAR.

NICOLE: Ah, parar. Yeah. And I was going to say there’s also PARAGUAS. So, the water, that’s just regular umbrella.

DANIEL: It stops the water.

NICOLE: It stops the water.

DANIEL: And PARACHUTE is a paracaídas, which means it stops the falling. In every case where you got a PARA, it stops the thing. A PARABRISAS is a windscreen. It stops the wind. So, this is going back into my Spanish, but I think it’s pretty solid. I’ll check that out.

NICOLE: Yeah, no, that seems right now that we’ve got several examples. Well, I was wrong about that etymology, perhaps because PARA is a verb and also a preposition.

DANIEL: Exactly. But the fun thing is, English did this too, but only for a little while. There’s a thread by David Thomas Moore on Twitter, or now X. He says, “It’s called the exocentric verb-noun compound agent noun. Almost all these words were coined between 1550 and 1700. And they’re always something bad or disreputable. For example, a CUTTHROAT or a PICKPOCKET or a TURNCOAT.” Even names like Shakespeare and Falstaff. So, those are interesting. I feel like not having any sort of clue as to what happens when you plonk two nouns next to each other, could be a bit of a disadvantage, like our dog and our duck sushi is a little bit confusing. But I think it can also be a help because we can generate things very compactly and then just guess from context, which is what we usually do, and then if there’s a problem, we can reword it or ask questions. And that’s just how semantics goes.

NICOLE: Yeah, I mean, also, one of my favorite things to talk about is sociolinguistic competence. And so, that’s where I went first, which is like, we know something about dogs, we know something about ducks. So, it’s actually whenever we have ambiguity, it can frequently be resolved by contextual information or social contextual information, that we in this society are more likely to eat one over the other.

DANIEL: That’s right. So, real-world knowledge also plays a part, and that’s part of competence.

NICOLE: Yeah.

DANIEL: Awesome. Thank you, Wolf, for that great question. This one’s from Jenna via email, hello@becauselanguage.com. “I recently heard about a company, who I don’t want to name and give publicity to, who was creating a campaign to draw attention to breast cancer screening, while at the time, apparently using chemicals linked to causing breast cancer. What do you call greenwashing when it’s not specifically about the environment? Image washing? Image laundering?” What’s your perspective on this, Nicole?

NICOLE: Yeah, so we have washing as a productive suffix here, not only for green, but when the World Cup was in Qatar, there was sports washing.

DANIEL: Yes.

NICOLE: Accusations that they were trying to… So, Jenna mentions image laundering, that they were trying to improve their image by having this sporting event. So, I think it’s fairly productive. Actually, it’s interesting that she has chosen this example. I’m a breast cancer survivor, so I know this word because I’ve seen it. And it was also recently, October, and October in the United States is Breast Cancer Awareness. So, you see this everywhere. Pink washing because of the pink ribbon that we use to represent breast cancer awareness. And some sources that I checked into will say that’s just sort of trying to get the money and make their image look good, and it doesn’t really have the implication that the company is using chemicals that cause cancer. But there are some definitions that do specifically refer to the phenomenon that Jenna’s talking about, where the company is using bad chemicals and then also then trying to get the positive publicity for being aware of this. There is another meaning of pink washing, which is similar, but it’s for LGBTQ issues.

DANIEL: I’ve seen that one too. Yeah.

NICOLE: If you see it in June in the US, it’s pink washing. If you see in October… it’s the LGBTQ one. If you see in October, it’s the breast cancer one.

DANIEL: Right. And we had that one as a Word of the Week a while ago, rainbow washing, which is for the LGBT stuff, and also rainbow capitalism. So, there’s a number of terms floating around. Hmm. I like washing. Productive washing is very interesting. And I think out of all those for this, I like image washing the best, just as a general sort of term for any kind of laundering of image. I took a look at the history of whitewashing because this is, of course, where it all goes back to. In the 1500s, whitewashing was to bleach something, to wash it and make it white. But it didn’t take long for the paint, meaning to come in to cover or coat a wall or building with whitewash, 1591.

For the 1700s, you started to see to cover the face with makeup to make you look lighter. But also, we see, to conceal the faults or errors of. So, it took about 100 years, but it made it. Also, we see in the 1800s to beat a team by a very large margin. “They whitewashed the other team.” Nowadays, we see shellac, but in elections sometimes. So that’s the history there. Yeah, I think I like image washing as a general thing. And then specifically, you can go pink washing, if that works.

NICOLE: I like image laundering. I think pink washing is good. I actually like image laundering, I think, because of analogy to money laundering.

DANIEL: Oh, yeah. That’s a little bit more transparent. Okay, well, look, it sounds like we got a number of choices, and these terms are duking it out, so we’ll see what happens.

NICOLE: Yeah, this is a good question.

DANIEL: It is a good question. Nicole, thank you for sharing that experience, and I’m just wishing you all the best for continuing on.

NICOLE: Thank you.

DANIEL: Yeah. Thanks, Jenna, for that question. Let’s go on to a question from Chris. Chris sent us a message on SpeakPipe. I wish Ben were here because Ben has been pleading for people to send us messages on SpeakPipe. You can do it on our website, but let’s hear what Chris has to say.

CHRIS: Hi, Because Language team, I’m Chris from Minnesota, and I have a small gig where I talk with Taiwanese people in English to kind of practice and build up their self-esteem. Because in my experience, in Taiwan, the people there, their English is usually pretty good, but they’re just afraid to speak it. So, I was talking with a young kid, and I thought it was interesting because we were doing a reading and we read the word, MVP. And I wasn’t sure if he understood what it was, but when I asked him, he was able to identify MVP as it means more important than VIP. But that’s kind of true in how I would use it in American English, but not quite. And I don’t know exactly how… like, it seems to be used pretty widely in Taiwan in that more intense form of VIP, and it’s kind of separate from the sports route. So, I found that to be really interesting because they got that essence of it, but they pulled away from that more specific usage. Anyway, thanks for creating your content… Oh, I shouldn’t say content. Bye.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Why shouldn’t you say content? That’s really funny.

NICOLE: It’s like offensive. Oh, you don’t make content. You make a high-quality podcast.

DANIEL: I’m not a content creator. You take that back. Nah, content is fine. Wow. So, it sounds like in Taiwan, MVP is being uncoupled from its sports meaning and being used to mean like a really, really important VIP. Wasn’t that interesting?

NICOLE: Yeah, I think I have a theory before you tell me with the research you’ve done.

DANIEL: I don’t know. I really don’t.

NICOLE: VIP, to me, seems older, very important person. Older and more widespread. MVP outside of sports seems to be a more recent coinage. And if you’re not familiar with American sports, which always have this person who’s designated as the MVP, I don’t know about Taiwanese sports, and you know VIP, then you could imagine it. Oh, yeah. Okay. I know VIP. I know that M is most. It must be most important person. Great, we got it.

DANIEL: Yeah. And they both have VP in them, so that must be related somehow or whatever. I think you’re right. I think that’s probably what’s happening. It’s like a cultural thing, but also presumed etymology. That’s as good as any answer that I had. I see that in the Oxford English Dictionary, it’s most “valuable player given to the player in the league deemed to have contributed most to his or her team’s success. Also, in extended use.” So now we start seeing it in business. And it is a bit confusing because it’s also a business term, the minimum viable product that you can get out there.

NICOLE: A businessy business.

DANIEL: In businessy business. The Globe Corpus says that it’s huge in the Philippines, but that’s probably because there’s a celebrity, a businessman, Manuel Velez Pangilinan, who is known popularly in the press as MVP.

NICOLE: Oh, I was thinking about that meme that has Kevin Durant, “you the real MVP”?

DANIEL: Oh, yeah.

NICOLE: It’s like ancient in meme world [CROSSTALK] [LAUGHS] but every time someone says MVP, I just think about that meme. So, the extension has not gone that far from me, “you the real MVP.” And I, in fact, have given that as a compliment to people before… when it’s a nice way to respond if someone really thanks you effusively, like, “Wow, you’ve done so much. Thank you so much for coming on our podcast. You the real MVP.” [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Do you remember how people were saying “you da man” a while ago?

NICOLE: Yeah. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Something I stayed away from. I’ve become really aware of taking on memes where African American English pronunciation is a focal point. I’m just like, “Nah.”

NICOLE: Yeah. There’s a lot of those. That one is sort of a double whammy because it’s got the da, like the T-H stopping for the. But it also has zero copula, which is a showcase feature of African American English. And not only is it like a really common feature of African American English, it’s also a heavily policed one.

DANIEL: Yeah.

NICOLE: So, what feels like, I think, a little gross to us about that is it’s not just, “Okay, this phrase that became popular that originated in African American English, which might be kind of fine in broader use,” it’s specifically using a feature that people are genuinely punished for.

DANIEL: Yeah, exactly. It’s okay when I do it, but not okay when actual African American speakers do it. That must be why it gave me the ick a little bit.

NICOLE: Yeah.

DANIEL: All right. Well, I think what we’re seeing here is the birth of a false friend. They got to get started somehow, and I think you provided a really good explanation for how it got tracked onto that channel. Thanks for that.

NICOLE: I think it could come back too, because it’s already being extended in wider use in the United States, for example. We might just start using it as most important person.

DANIEL: We might. Maybe it’ll get imported, that would be really cool.

NICOLE: Yeah, full circle.

DANIEL: Thanks, Chris, for that. And anyone else who wants to give us a message using your own voice, just head over to becauselanguage.com. We’ve got an extension there for SpeakPipe. It’s really easy, just click a button and say stuff. And then, check it out to make sure that you sound okay, because unusable audio is unusable. But thanks for that, Chris. All right, time to play a game. You ready to play Related or Not? Our favorite game.

NICOLE: Yeah. I feel heartened by the last few that I’ve listened to where your cohosts were not necessarily correct, but it was educational for everyone. So, low stakes game over here.

DANIEL: Low stakes or no stakes are the best kind of stakes. This one’s from Andy of Logophilius, who says, “A different tack for Related or Not. Here are three words. At least two of them are likely etymologically related. If y’all don’t already know the answer, I think this could be a fun discussion. Here are the words. Pin, pen, pencil.”

NICOLE: Oh, no.

DANIEL: Yeah. If you have the PIN and PEN merger, then this will be tough.

NICOLE: Daniel, I have the merger.

DANIEL: Oh, no. What have we done? Argh.

NICOLE: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: You just go with it, I’ll compensate.

[LAUGHTER]

NICOLE: As an aside, one time I was in the bookstore at the University of Pennsylvania, and I saw a P-I-N next to a P-E-N. And I was at the bookstore of P-E-N-N, and I took a photo and I was, “Ah, it’s a pin, pen, Penn.

DANIEL: I don’t know what to do. There’s too many pens! Tell us about what variety of English do you speak that lends you to have the PIN-PEN merger?

NICOLE: I’m from Central Ohio, but all of my white people are Southern, and all of my Black people are African American English speakers. And so, everyone that I grew up with had a PEN-PIN merger.

DANIEL: Wow. So, you say, “Hand me the pin?” How would you say, “Hand me the pen?”

NICOLE: “Hand me the pin.”

DANIEL: And it could be a pin or a pen. Okay, cool.

NICOLE: Yeah.

DANIEL: All right. Well, do you have any guesses? I have an answer that I wrote down before I looked it up so we can both play.

NICOLE: I’m, like, using my knowledge about the world because I think if P-E-N and pencil are related, it’s not very fun. So, I want to be contrarian and say that pencil and P-I-N are related. But I don’t know how.

DANIEL: PENCIL and PIN, okay, are related.

NICOLE: Yeah, why not?

DANIEL: So, you think that PEN would be the odd one out?

NICOLE: Yes, I think that P-E-N is the odd one out.

DANIEL: That’s exactly what I thought too. And I think I remembered from dimly in the past that PEN and PENCIL are unrelated. So, I thought that maybe PIN and PENCIL might be related, and that PEN was the odd one out. All right. Okay. We both guessed the same thing. Let’s see if we’re right. We were both right that PEN and PENCIL are not related to each other.

NICOLE: Yay.

DANIEL: PEN is from Latin penna, a feather or a plume. By the way, I pull this from lots of sources, but this time I just looked at Etymonline, the online etymology dictionary. It’s super good. PENCIL comes from a different place, Latin penicillus, which is where we get penicillin from.

NICOLE: Penicillin, yeah.

DANIEL: A painter’s brush or a hair pencil. Literally, a little tail, which I think is why PENIS is also related to all of these.

NICOLE: And maybe PENINSULA.

DANIEL: Ah, you bring in the INSULA. Yes, Latin. Wait a minute. Latin INSULA. But what’s the PEN there? The tail?

NICOLE: Yeah, that’s sticking out into the water.

DANIEL: Okay, let’s check it out. PEN… we always get more questions when we do this game. Looks like PEN… No, the PEN is not tail. It’s “nearly” or “almost” or “practically”. It’s practically an island.

NICOLE: I was trying to do a folk etymology.

DANIEL: Oh, darn, and I didn’t let you. Sorry about that. But PIN, for its part, comes from Latin pinna, a feather or a plume, just like PEN. So, we were both wrong. PENCIL is the odd one out, and PIN and PEN are related. Dang it.

NICOLE: Mmm, interesting, yeah.

DANIEL: And I’m noticing on the website, for PEN, the derivation is Latin penna. But for PIN, the derivation is given Latin pinna. Was there a PINNA-PENNA alternation in Latin?

NICOLE: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Does this merger thing go way, way back? I don’t know.

NICOLE: I mean, those vowels are awfully close to each other in a crowded space in English, so…

DANIEL: They are. Maybe it was that way in Latin. I know that the thing about IN- being “not” and IN- being “inside of”, like INFLAMMABLE, I know that that was also a problem in Latin. That confused people as well. All right, so thanks, Andy, for that one. And then finally, Diego gave us one, and I didn’t know the answer. So, I just made my guess. And then I looked it up. Related or not: PUPPY and PUPPET.

NICOLE: PUPPY and PUPPET. The only possible connection I can think of is that they are both very cute. So, I’m going to go with yes on the cuteness. Maybe the toy was named after the cute animal. That could happen.

DANIEL: Okay. You think the toy was named after the cute animal? Okay. So, my first instinct was no, but I don’t know why. And then I found myself going through a process, like, do the words look similar? Yes. Do they mean kind of similar things? Yes. For cuteness. Language of origin? Don’t know. I thought PUPPET has to be French with that -ET ending, because we saw that with TUFFET. Like, “Little Miss Muffet sat on a tuffet.” What the hell’s a tuffet? It’s a small tuft, a tuft of grass. She’s sitting on a tuft of grass. And then, morphology, both small. So, I thought all right, I don’t have any reason to go no. So, I’m going yes. We both went, yes. And then you’ve already kind of answered the bonus question in case we both said yes. Do they have the same ancestor, or is one derived from the other? And you thought that PUPPET came because it was named after PUPPY, because puppies are cute. So, we named the PUPPET after that?

NICOLE: Cute, small, malleable thing, yes. [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: I thought that maybe PUPPY came from PUPPET. I thought that maybe PUPPET got named first. Okay. So, I looked it up. The answer, we were both right, they are related. This is not one of those funky you’d expect it, but it’s not. And I got it right all the way down. PUPPY does come from PUPPET. Woo.

NICOLE: That’s one of those hard ones, because you know that we’ve had dogs for longer than we’ve had puppets. But did we have a different word for “tiny dog” or “baby dog”?

DANIEL: We did. We did have a different word for tiny dog, and the word was WHELP.

NICOLE: Ah, that’s the missing link.

DANIEL: That’s the missing link. And so, PUPPY pushed out WHELP because it was cuter. Who wants a whelp?

NICOLE: No, puppy’s much cuter.

DANIEL: What I didn’t see is that PUPPET is also related to PUPIL. We did a whole thing a couple of shows ago about PUPIL.

NICOLE: Oh, I remember the PUPIL discussion about the small image in the eye. Yes.

DANIEL: That’s it. Also related to pupa… And this one, I didn’t see coming: POPPET. I always call my two girls poppets, but I didn’t realise it came from Latin pupa, which is girl or doll.

NICOLE: Nice.

DANIEL: So, here’s the path. You start with Latin pupa, a girl or a doll. Okay, whatever. From there, you take the doll to French, and you add ‘et’ to it, and then you get poppet. And then from there, it’s just a vowel change to get puppet. Now, for puppy, you just take off the French diminutive ‘et’ and you add an English diminutive E. That was the 1500s. And, in fact, even the Century Dictionary says, “A little dog appears to have been called puppy because it’s petted as a doll or a puppet.” So, maximum points for me, and you also did very well.

NICOLE: Half point for the goal.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: You get one and a half. All right, so thanks for that, Diego. And we’d love to see all the variations you’re all coming up with for Related or Not. We’ll have another one from Pontus on our next show. All right, ready to get back to some questions? I think these will go a little faster.

NICOLE: Yeah. Questions.

DANIEL: Michael, via email, hello@becauselanguage.com, says, “Hi, guys. Love the show. I remember learning about vocal fry.” Nicole, you got some vocal fry?

NICOLE: I do. And also, I study prosody and voice quality, so we’re in my universe.

DANIEL: Oh, good. I’m so glad you got this one. “Vocal fry, and how it’s becoming more popular in language in the newer generations.” Is that true, by the way? Old men do it. Noam Chomsky does it.

NICOLE: Uh, yes, kind of. Okay. In the United States, yes, kind of. I’ll say that.

DANIEL: Okay.

NICOLE: It’s, like, not as dramatic as people think, but, yes, there is a trend in overtime, we see.

DANIEL: I mean, have people always been frying but this is the first time that it’s become a generational or gender marker?

NICOLE: Yes. People have always been frying because we can’t help but fry. We don’t usually call it vocal fry. We call it creaky voice in the literature more often. So, what happens, one way that you get to creaky voice is you have dropped out of the bottom of your fundamental frequency range. Your f0 or what we hear as pitch range. And now, you are getting in aperiodic closure of the vocal folds, like I just did there. So, whenever you are running out of air, you’re going to be at the bottom and you’re going to get an aperiodic closure. Which is why in languages that have creaky voice as something that’s not like phonemic because some have it as something that differentiates vowels. you tend to see it in a phrase final position because when people run out of air, that’s where they go.

DANIEL: Why wouldn’t you? Yeah, okay, makes sense. I’m reading also that the arytenoid cartilages in the larynx are drawn together, they get compressed rather tightly, becoming relatively slack and compact. And then you get this pulsing. Okay.

NICOLE: Yes.

DANIEL: Now, let’s go on to Michael’s question. “I do this a lot as I’m a millennial and I have a deep voice. But I noticed that when I started vaping, my vocal fry disappeared, and I don’t mean due to a social cultural change. I lost the ability to make the sound or overexaggerate it. I never really smoked cigarettes. And I’m not about to start just to test a theory. But is it likely that the appearance of vocal fry is due to less people smoking? And, by extension, will disappear again if everybody starts vaping at the same levels we smoked in the 30s and 40s? Or does that just sound insane, and I should see a doctor?”

NICOLE: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: So, the hypothesis is, he starts vaping, can’t do vocal fry anymore. Can you think of any mechanism by which that might be happening?

NICOLE: No. And in fact, I would predict the opposite. One thing I want to say is, Michael is saying that the vocal fry disappeared and it wasn’t social or cultural. You will never know that about yourself.

[LAUGHTER]

NICOLE: You will never know that about yourself. It’s hard enough to know it about other people.

DANIEL: Yeah, yeah. Good point. My intuition is that it’s not social or cultural, yes.

NICOLE: Maybe Michael’s right. We don’t know. It could definitely happen that the crowd that he vapes with are just not people that use vocal fry, and so it’s a coincidence. I don’t know. There’s lots of things that could have happened at the same time.

DANIEL: Argh, this is tough.

NICOLE: So, whenever we have anything that stresses out our vocal tract, we are more likely to get aperiodic noise of any kind.

DANIEL: Aperiodic noise being the fry, being the creaky voice?

NICOLE: Yes.

DANIEL: Okay.

NICOLE: This is a type of aperiodic noise, I think, but not necessarily. There was much made about, “Oh, the young women are doing vocal fry, and it’s ruining their vocal folds.” It doesn’t cause damage. It doesn’t. But if you’re exposed to chemicals or smog or cigarette smoke or whatever, you’re going to have a harder time doing a sort of clear, modal voice where your vocal folds are sort of coming together periodically in this beautiful way, and they’re totally undamaged and all of that. So, you can imagine this when we hear people that have been smoking for 60 years. They don’t have this nice, clear, light voice that’s very periodic, like a beautiful opera singer or something. It’s different.

DANIEL: [IN HARSH VOICE] They sound like they’ve been smoking Chesterfield Kings. “Come over here, kids. Sit on my lap.”

NICOLE: And that’s actually a different phenomenon, what you’ve just done here. It’s harsh voice, which is something that happens if you have to really force the air through your vocal folds more often. And it’s the same thing because they don’t come together smoothly because they’re damaged on the surface, where they would come together. Yeah, I don’t think that it’s the vaping. [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: Okay.

NICOLE: Yeah, sorry. Michael, don’t go see a doctor, you’re fine. But maybe investigate other ways that could be influencing your vocal fry. I would be really surprised if he genuinely can’t do it, because pretty much all English speakers do it when we run out of air. It’s a very functional way to do phrase final things for anybody that before it became like a social panic about millennials, there was vocal fry in the past too in those places. Maybe he is noticing that he’s not doing it in the same places he was before, but he probably can do it somewhere in his phrasing.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, let’s see. I just did a little bit of research, and I found something by Sarp Kurtoglu of the Osborne Head and Neck Institute. One of the first web pages that came up when I looked for vaping effects on the voice. And it says, “Vaping produces a highly irritating vapor that is inhaled past the vocal cords, causing inflammation of the lining of the vocal cords.” A lot of people say hoarseness, but this is the opposite of hoarseness. So, okay. But then, Dr Kurtoglu says, “If the delicate lining of the vocal cords are exposed to hot, vaporised chemicals, the tissues are likely to undergo change and lose their ability to behave normally. This may produce hoarseness,” listen to this, “Loss of vocal range, voice fatigue, or vocal injury.” And I just thought, well, vocal fry is like… creaky voice is the lowest register of your voice. So, if you’re vaping and it’s doing something like affecting your vocal flexibility, then maybe that would be an explanation for why you’re not able to drop into that range anymore. I don’t know.

NICOLE: Ah, okay. Yes. I could see one thing happening, because Michael says he has a deep voice. He might be using a higher part of his vocal range, because when he tries to use the lower part, it’s actually too aperiodic now, if there’s damage. So maybe, he can’t drop into creaky voice, his voice just drops out, like he doesn’t get any closure of the vocal folds anymore. So, he’s got to speak higher. So then, I’d want to know if overall he perceives himself as having a sort of higher range.

DANIEL: That would be interesting. Okay, well, look, Michael, if you do have any questions, talk to a medical professional who can give you specific advice based on your body, your needs, and your medical situation, and your history.

NICOLE: Disclaimer. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: I got to do it. [CHUCKLES] But yeah, it’s just a fascinating interaction of society and chemistry and apparatus, don’t you think?

NICOLE: Yeah, I mean, I have wondered about this a lot, the role of our environmental exposures and chemical exposures to what we see as the generational changes of what people imagine as vocal trends because I think there is something intuitive about what he’s saying, which is that if everybody’s smoking, then that’s going to create a sort of different norm for how we expect people to sound versus not. So, yes, I can see that something would change if people were vaping, but I’m not sure that it would be vocal fry.

DANIEL: Okay. Interesting. Well, Michael, thanks so much for that question. I really enjoyed sort of talking through that, got me into an area that I don’t usually go. So, thanks, Nicole, for your expertise on that as well.

Glenn, via email says, “Hello Becausians,” I like being a Becausian. “I wanted to share something I’ve discovered about the English language. I’ve heard Daniel express a view sometimes that disagrees with the common conception, right or wrong, that English is the hardest language to learn.” I don’t think… I’ve heard guests say, and I kind of agree, that it’s one of the easier ones. It’s not on the hard side.

NICOLE: Well, okay. No, this is ridiculous as a claim because the hardest language to learn is the one that’s farthest from the one you already speak.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s true, because it would take me a really super long time to learn Korean, Japanese, different language family. Also, when I’m being a bit facetious, I say the hardest language to learn is Sentinelese on the Sentinel Islands because they have very poor relations with outsiders, and they will kill you.

NICOLE: There you go. [CROSSTALK]

DANIEL: You’re not going to learn that language. No, you’re not learning that. Anyway, Glenn continues, “I am a person who has learned where correctly to place apostrophes.”

NICOLE: Correctly… Glenn, you’re hurting my sociolinguist soul! Sorry, continue. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: I just like how he refused to split the infinitive there. Did you catch that?

NICOLE: “Correctly to place”, yes.

DANIEL: “And one who believes that the wrong placement of them makes things more confusing. I know how to make the pronouns plurality or singularity agree with concepts such as each and all. I am also one of those who gets annoyed when someone uses the word impact as a verb. Part of this is because of my age, we were taught differently.” I try to be welcoming to prescriptivists on…[CROSSTALK]

NICOLE: Yeah, but Glenn doesn’t like language change, that’s what Glenn’s saying. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Maybe not. I sometimes say annoyance is a choice.

NICOLE: Yeah, there you go.

DANIEL: Okay. “I therefore happily identify with those who bleat at Sammy J. It’s not pronounced pronounciation, and you don’t mean literally. You mean figuratively. But,” says Glenn, “I have been forced to recognise something fairly insidious about the English language as used by those of us pedants.”

NICOLE: Okay, self-identifying. All right, Glenn knows who he is.

DANIEL: Let your freak flag fly, brother. Be who you are. We love you anyway. Just don’t hate on people. Don’t be a jerk. But it doesn’t sound like he’s being a jerk. So, cool. “English exceptions to all the rules which over the centuries have resisted modification are what makes it hard. But I now believe it is intentional. I don’t mean COLOR and COLOUR. That’s an example of a modification that’s become cultural. I mean, as an example, TROUGH, ROUGH, THROUGH, BOUGH, BOUGHT, SLOUGH, ENOUGH, and on. I mean Leicestershire, pronounced Lestershire, Wodehouse pronounced woodhouse, Dalziel, pronounced dee-el, apostrophe pronounced apostrophEE. Over many centuries, these have become examples of dog whistling not knowing these exceptions is, and for many hundreds of years now have been a means of distinguishing between those of us who know and those who don’t. Those who know are us. Those who don’t are them, which usually means the illiterate. Please give me your thoughts in an entertaining manner.” Nice closing.

NICOLE: Glenn has discovered shibboleths.

DANIEL: Shibboleths. I love shibboleths. Do you have the story? Why do we call them shibboleths?

NICOLE: It’s not going to be as well researched as yours, so fill in the blanks here. I believe this is the Bible, the Old Testament.

DANIEL: Yes, indeed. Book of Judges.

NICOLE: Yes. Okay, great, the Book of Judges, where there was a community of people who had a /ʃ/ instead of a /s/, and they were able to tell who was an interloper because the interlopers spoke a language that did not have a /ʃ/, only a /s/. So, if people said SIBBOLETH, they would kill them.

DANIEL: That’s right. The Gileadites had the /ʃ/, and there was a massive battle between the Gileadites and the Ephraimites. And the Gileadites, they won, and they controlled the bridge or the crossing across the river Jordan. So, they made everybody say SHIBBOLETH, and the Ephraimites couldn’t say it, so they would kill them. And according to legend, they killed 42,000 of them that day as they were trying to escape.

NICOLE: You know what the difference is between /s/ and /ʃ/ acoustically is like where the noise is concentrated in the signal. So, like 42,000 people died because their frequency wasn’t high enough for these people? Ooh.

DANIEL: These frequencies matter. A little bit of tongue retraction. By the way, I am thrilled. I use African American Siri on my phone, and I’m thrilled that she’s got S-retraction. She says sh-treet.

NICOLE: Oh, Voice 2.

DANIEL: Yep, that’s the one. Love her.

NICOLE: Yeah. A lot of people are doing S-retraction now, I think in the US.

DANIEL: It’s all over the place. It’s in Aush-tralia as well. Shtralia, mate.

NICOLE: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: So, I think there are lots of examples where people have seized upon some tiny linguistic variable and turned it into a social shibboleth. Like, one of my ABC Australia radio mates, I have a gig where I talk every week about language, it’s super good. But they always get calls from people who call them out on things. And one of them was “us” and “uz”. He said, “Give uz a listen” or “Give uz a call.” ~It’s US!~ You could imagine the complaining. So, why do we have these exceptions?

NICOLE: Well, I guess Glenn gave a lot of examples that were about sounds, and I’m more of a sound expert. So, I don’t know about the grammar, but…

DANIEL: Let’s stick with placenames, then let’s go with placenames.

NICOLE: Yeah. I think that I was a little bit glib when I was like, “43,000 people died because of center of gravity of S.” Yeah, but also because we imbue it with social meaning. I don’t remember who first said this, but it’s a very good quote. So, if we can track it down, please do. “If God or whatever deity had not invented the Tower of Babel, humans would have done it ourselves.”

DANIEL: Oh, interesting. Yeah. Yes, we do. Yes, we do.

NICOLE: Because we actually need linguistic variation to do social things. It is an essential part of the signal. Back in the day, pre-sociolinguistics, people imagined that all of this was just meaningless noise. Or they had a sense that over here, they say it this way, but over there they say it that way but there wasn’t necessarily a fully conceptualized idea that it was socially meaningful in other types of ways. And now, we know that it’s always socially meaningful. If you think about the town in Kentucky, Louisville versus Loueyville, you are doing something when you are pronouncing that one way or the other way. Or like…

DANIEL: [CROSSTALK]

NICOLE: …when I first moved to California, I was hosting trivia when I first moved to California, and there was a question about Marin County, which is in Northern California, and I live in LA, and I had never heard of Marin County because I came from New York City and Ohio before that. And so, I read it in this trivia. I was the MC, I read it as Ma-rin County, and they laughed at me because they all knew, and I didn’t. I had marked myself as an outsider. Trivia is a low stakes situation. They weren’t going to throw me off the bridge. But it’s kind of useful to know who’s from around here maybe sometimes.

DANIEL: “You ain’t from around here, are you.”

NICOLE: Yeah, y’ain’t from around these parts.

DANIEL: So, there’s Marin County. I knew that one because it’s referenced in the Dead Kennedys song Moon over Marin. But what other place names do you know? Like, in West Australia, if you say that somebody’s from Albany /al/, you don’t come from here, it’s Albany /æl/. Everyone says Albany.

NICOLE: Yeah. This is so weird. Los Angeles has a lot of Spanish origin place names that are pronounced with English phonology even by Spanish speakers.

DANIEL: Wow. Okay. Fascinating. Like what?

NICOLE: So I had a friend who was running for city council in this town called Duarte, D-U-A-R-T-E. And Spanish speakers that are Spanish dominant, like recent immigrants will say Duar-te. And it’s a Spanish origin word, Duar-te. But people who are like bilinguals who grew up in Southern California will say Duardee, the way that only sort of L1 English speakers will do. They’ll say Duardee. And my friend was trying to figure out what he should call the town when he knocked on doors, because he realized that he would be sort of aligning himself with more recent immigrants if he said Duar-te. And maybe, is that advantageous? Or should we say Duardee? I don’t know. It was a real problem.

DANIEL: Gosh. I mean, in the case of Louisville, what you’ve got is just a normal sound change. These things squash a little bit. So, here’s what I think is going on. I think normal sound change is happening, and then that’s kind of advantageous. Like, we don’t mind if that happens, because then it does have a social function. It allows us to see who’s in group and who’s out group, which is a very human thing. But then, I was looking at Derrida, which I never normally do, and Derrida had an interesting insight, and that was that language isn’t just for showing group membership, although it does that, but also displaying knowledge of difference.

NICOLE: Yes.

DANIEL: Which I think, in Glenn’s case, might be a big motivator. Like, you’re being able to say, “I’m one of the people who knows the difference between,” and then insert your arbitrary grammar shibboleth here. But we get rewarded for that sometimes. Feeling like you are someone who knows you’re comprised of versus comprises that kind of thing. I mean, what was that one guy on Wikipedia who spent all that time changing all of the examples of comprise? Why would we do that? Because it was important to who he was, some notion of… He was performing language just like everybody else.

NICOLE: This is very, very important. I think you’ve hit on a crucial point. When people, self-described pedants or the grammar police or whatever, are confronted with a sociolinguist, every sociolinguist will be like, “You’re a pedant. Stop policing people. This is problematic because historically that has been used to oppress people. So maybe, be careful with that.” Many people who identify as the grammar police will be like, “Yeah, okay, you’re right. This is just my thing, my hobby, whatever. Fine.” But sometimes people get a little defensive about it. And my experience is that they feel like you’re taking something away from them. No, no, no. I took the time to learn that it’s supposed to be comprised. What is it supposed to be? I don’t remember. Comprised of? From?

DANIEL: Who cares?

[LAUGHTER]

NICOLE: Here I am, not knowing the prestige standard.

DANIEL: I purposely am ignoring prestige standard because I don’t want to care.

NICOLE: Yeah. To the point, in my research, this happens with middle-class African American speakers who were very policed by their family or teachers or community to not say things like “ain’t” for example. And so then they will say to their kids, or kids in the community, “Don’t say ain’t.” Well, they literally in some cases had the AIN’T beaten out of them…

DANIEL: Literally.

NICOLE: …by another generation. And the argument will be, ‘Well, I learned to do it the “right way,” so you should have to too.’ Because what that generation that was trying to beat the AIN’T out of them was doing was to give them that social power that they would get by using the standard. And they get worried that if the kids don’t do that, we’re still marginalized. It’s still racism. That if the kids go back to using ain’t, they will lose the social power that they’ve tried so hard to accrue. So, I’m sympathetic to this in a certain way.

DANIEL: Yeah. Except, I don’t know, if Glenn belongs to any minoritised groups or whatever, but as a white dude, I still sympathise because I’ve said this before. I was a kid that did well in school. I was eager to please teachers, like displaying my language knowledge made me special. And so then, we come along, we try to take that away, and people are going to fight us back. So, what do you think our response should be to pedants? We could say, “You’re a good language noticer. Pat you on the head.”

NICOLE: [CHUCKLES]

DANIEL: And then, could we then say, “Noticing things about language and knowing stuff about language is super good. Let me just pivot you a little bit so that you can notice all these other really cool things.”

NICOLE: I think that’s how we all become linguists. Many linguists I know were the grammar police when they were young people, because they were noticing language, but they didn’t have anywhere to put that. I noticed.

DANIEL: How can I be special for that? Yeah.

NICOLE: Yeah, we just make them into linguists, I guess. [LAUGHS] “Join the cult.”

DANIEL: And this is why community is important. Now, you’re special and here’s a community that values noticing language things, but in a positive way that makes a positive social difference. I think maybe just helping pedants to pivot a little bit, which is maybe why Glenn listens to the show. I don’t know.

NICOLE: Yeah, we don’t want to be too hard on Glenn. I’m glad that he wrote in, and this is an interesting question.

DANIEL: Super good.

NICOLE: You can do whatever you want with your own identity. You can be very proud of knowing the prescriptive way to pronounce every single word in English. Good for you. You can take pride in whatever you want. The problem is, when you try to enforce that sort of judgment on other people to gain power over them, that’s always the problem.

DANIEL: Okay. So, I wanted to ask you a little bit about what we should be doing as linguistic podcasters or as public linguists. And it sounds like we’ve got a few answers, that we can encourage people to be good language noticers, but then we can also suggest better communities, better things to notice, instead of the rather, for me, boring particularities of usage, we could notice amazing things about language in the world or language through time. And by pointing things out and by building good communities, we can make prescriptivism, which isn’t always bad, less… We can make recreational prescriptivism or prescriptivism in the service of oppression less attractive. Would that be…?

NICOLE: Yeah, there is a way in which people just notice and don’t necessarily oppress, and it’s when they notice varieties that have equal or more prestige than theirs. So, Americans in general love British people, love the way the British people talk.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. “Oh, you sound so highfalutin’.”

NICOLE: Yeah. An American speaker goes to England, and they meet a Londoner, and they say, “Oh, they call it the telly.” Or they say, “In hospital.” And it’s not used to oppress them. It’s just like, “Hey, cool difference.” We could all just be like, “Hey, cool difference.”

DANIEL: Hey, cool difference.

NICOLE: Where’d it come from?

DANIEL: And the differences are the same. Like, you see somebody from England, and you say, “Wow, they drop their R’s,” and then you see somebody from African American English. “Eww, they drop their R’s,” but it’s the same goddamn thing.

NICOLE: So silly, right?

DANIEL: So, pointing that out, I think, is another good thing. I just did a whole thing on Shakespeare. Oh, Shakespeare. And how Shakespeare did all kinds of things. Like, he used negative concord. He used THERE’S with plural objects, like, “There’s daggers in men’s eyes. That’s Macbeth. He used multiple superlatives in the same sentence, like the most unkindest cut of all. So, showing that, “Oh, Shakespeare…” He used the word LEARNINGS, which for some reason drives people crazy. Shakespeare did all the things that drive you crazy, and yet we… And so I love to sort of haul these things out and show that, “Actually, the things you complain about, you might not mind them in other contexts.”

NICOLE: Yeah. I always do appeal to Shakespeare as an authority, because everybody had to study him as this great author or whatever. I think there’s that. Hey, not only the people that are marginalized in your society do this, people that you revere do or used to as well. So, to focus on… look, there’s the linguistic difference and judgment, and then there’s the social one. And if you can disentangle those, then it opens up a whole new world of investigation for you.

DANIEL: I think so too. All right, well, I think it’s time to close our mailbag. Thank you for coming in there with me and answering these questions.

NICOLE: Yeah, of course. It was really fun.

DANIEL: Like to say thanks to everybody who gave us ideas for this episode? Thanks to the team from SpeechDocs for transcribing our words. Have you ever heard of a podcast called Sandman Stories Presents from Dustin?

NICOLE: Yes, I have.

DANIEL: It’s very good. Thought I’d give him a shoutout. Most of all, thanks to you patrons who keep the show going. And, Nicole… you are the real MVP.

NICOLE: Oh, no, you ARE the real MVP.

DANIEL: Hey, where are you hanging out online these days? I don’t see you as much on Twitter, but I’m seeing you on Bluesky a bit.

NICOLE: Yes. I remain @mixedlinguist across the internet. Occasionally on Twitter, but it’s dark over there. So, I’m hanging out on Bluesky and Threads and Instagram, I guess.

DANIEL: Do you feel like you’ll eventually converge on one?

NICOLE: It’s interesting because I think that the academics that I follow have moved to Bluesky, but I haven’t found a place where the journalists and the other just like random cool people necessarily are. I think they might be on Threads, so I might have to keep my journalist people on one place and my academics on the other. But we’re still in the disruption. Where are we going to land?

DANIEL: We very much are. It’s so exciting. I actually don’t mind it. It makes it tough a little bit, but it’s kind of cool.

NICOLE: Have you heard that LinkedIn is like the hot new network?

DANIEL: Oh, really? Oh, man, I hate LinkedIn.

NICOLE: Yeah, there was AN article, I think maybe it was New York Magazine or something, but it was like, “The teens love hanging out on LinkedIn.” So maybe, we’ll all just go there.

DANIEL: Okay. Oh, my gosh. If you dig the show, you can support Because Language by giving us ideas and feedback. Where can you do that? On the socials. We’re becauselangpod on just about every conceivable platform, mostly Twitter, Facebook, Bluesky, and Mastodon. You can head over to our website becauselanguage.com and leave us a voice message on SpeakPipe, or even just send us a file of you talking. We’ll play it as long as it’s pretty good. You can send us an email hello@becauselanguage.com. Another way you can support the show is by telling a friend about us or even leaving a review on all of the places where reviews can be left.