We’re going deep into our Mailbag, and we’re going to answer all your questions.

- Why do we say “here you go” when we give something to someone?

- Why can we reduce something to /sʌʔm/?

- The thing is is, there are two IS there. Why?

- Some contractions seem to’ve appeared, and they look strange in writing. What other ones’re out there?

Listen to this episode

Video promo

Patreon supporters

Huge thanks to all our great patrons! Your support means a lot to us. Special thanks to:

- Iztin

- Termy

- Elías

- Matt

- Whitney

- Helen

- Jack

- PharaohKatt

- LordMortis

- gramaryen

- Larry

- Kristofer

- Andy

- James

- Nigel

- Meredith

- Kate

- Nasrin

- Joanna

- Ayesha

- Steele

- Margareth

- Manú

- Rodger

- Rhian

- Colleen

- Ignacio

- Sonic Snejhog

- Kevin

- Jeff

- Andy from Logophilius

- Stan

- Kathy

- Rach

- Cheyenne

- Felicity

- Amir

- Canny Archer

- O Tim

- Alyssa

- Chris

- Laurie (sorry we missed you last episode)

- new this time: Aengry Balls

And our newest patrons:

- At the Listener level: Jo and Franco

- And at the Friend level: Sam

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

Leak suspect Jack Teixeira appears in court as US reveals case against him

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-15/leak-suspect-appears-court-us-reveals-case-jack-teixeira-/102227008

‘go’ | OED blog

https://public.oed.com/blog/word-stories-go/

A Verb for Our Frantic Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/29/opinion/29winchester.html

Has ‘Run’ Run Amok? It Has 645 Meanings … So Far

https://www.npr.org/2011/05/30/136796448/has-run-run-amok-it-has-645-meanings-so-far

10 words in the English language with the most definitions

https://www.insider.com/words-with-the-most-definitions-2019-1

Here You Go | Grammarphobia

https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2018/03/here-you-go.html

The Un-mouthing of Sounds | Danny L. Bate

https://dannybate.com/2020/12/08/the-un-mouthing-of-sounds/

[PDF] O’Brien (2010). Debuccalization and supplementary gestures.

http://jeremypobrien.nfshost.com/papers/obrien_qe.pdf

Symbols and suits: a history of the Spade

http://honisoit.com/2019/10/symbols-and-suits-a-history-of-the-spade/

Double is | Yale Grammatical Diversity Project: English in North America

https://ygdp.yale.edu/phenomena/double-is

Obama says “is is”

Obama: The point was is that we’ve created a structure

Are You a Double-Is-er? | Slate

https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/09/double-is-why-linguists-think-we-sometimes-double-up-on-is-in-a-setup-payoff-style-sentence.html

Word watch: Tothersider

https://www.anu.edu.au/news/all-news/word-watch-tothersider

What is a t’othersider ???

https://www.outbackfamilyhistoryblog.com/what-is-a-tothersider/

Holes — Aengry Balls says: The bit about straws is from 16:36, but the whole video is relevant, really.

Is It Worth the Time?

https://xkcd.com/1205/

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

DANIEL: I shared this meme with my partner. “When loading the dishwasher, one partner is always the Scandinavian architect and the other is a raccoon on meth.”

BEN: Are you…? You’re… I have to imagine you’re the Scandinavian architect.

DANIEL: I am the Scandinavian architect.

BEN: Yeah, you bring that spectrum energy.

DANIEL: She was not amused, and she said, “I am not the raccoon.” And I said, “The thing about being the raccoon is that you don’t know you’re the raccoon.”

BEN: No one thinks they’re the raccoon!

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: I’m sure even raccoons themselves consider them erudite parliamentarians.

DANIEL: [MIFFED RACCOON VOICE] ~I could load a dishwasher.~

BEN: [LAUGHS]

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

DANIEL: Hello, and welcome to this bonus episode of Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. I’m Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. She’s a linguist and the world’s foremost advocate of buckaroo usage. It’s Hedvig Skirgård.

HEDVIG: I do like the term “buckaroo.”

BEN: I would like to consider myself a sidekick in the advocacy of buckaroo usage as well.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Like, it’s definitely Hedvig’s thing to champion, but I am right there next to her being like, “That’s right, Buckaroo Girl!”

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah, Buckaroo Girl.

DANIEL: He’s the sidekick in Hedvig’s championing of buckaroo usage. It’s Buckaroo Ben Ainslie.

BEN: Oh, no, I’d be Buckarette or Buckarini, something smaller! Something diminutive at the end of…

HEDVIG: Buckarino.

BEN: Buckarino. Yes! [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: That is the term.

BEN: That’s it. That’s the money shot. That’s good.

DANIEL: Or you could go full Spanish and go buckarito, is what you could be. I like buckarino better than buckarito, to be honest.

BEN: I do as well, because buckarito just sounds like money in a burrito, which just ruins both of those things.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that’s it.

BEN: Um, hello!

DANIEL: Thank you both for being here. This is great to have you, and we’ve got some really strong mailbag questions here. So, I wanted to get to them.

BEN: Mailbag episode! Come on!

DANIEL: We love our Mailbag episodes.

BEN: I love these. These are so fun.

DANIEL: They’re great. So, hey, if you are hearing this bonus episode when it’s new, it’s because you’re a patron. So, thank you for being a patron. You are helping us to keep the show going. You’re keeping episodes free for everyone.

HEDVIG: Pew pew pew.

DANIEL: If you’re listening a bit later when we get around to making them public, why not become a patron? For as little as a buck a month, depending on your level, you’ll get bonus perks like mailouts, shoutouts, bonus episodes, and every patron gets invited to live episodes, as well as access to our super-duper Discord community, which is a lot of fun.

HEDVIG: Mhm.

BEN: 100% less racism than a lot of the Discord servers you’ve probably heard of.

HEDVIG: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Also, guaranteed, no classified US documents.

BEN: Yeah. [LAUGHS] We are not trying to impress one another, clout-style, with Ukrainian military secrets.

HEDVIG: What kind of Discords are you on?

BEN: That’s so funny.

DANIEL: Oh, um, not me. I have nothing to do with that Discord.

BEN: Let’s catch Hedvig — and perhaps our listeners — up, if you’ve missed this particular story.

DANIEL: Shall we?

BEN: Do we have a news story about this, Daniel?

DANIEL: No, we don’t, but somebody snowdened. They snowdened.

HEDVIG: Yeah, but snowdened for the most hilariously juvenile reasons I’ve ever heard of, right?

HEDVIG: Is this the 21-year-old?

BEN: Yep.

DANIEL: Yes.

HEDVIG: I saw a Swedish person tweet about something I didn’t understand. Yeah.

BEN: So, quick catch up. You may or may not have heard that over the last several weeks, there have been a series of highly classified military intelligence documents being leaked out there into the world. America was tearing its hair out, basically, to figure out where this really damaging leak was coming from, thinking that it was some high-level official getting blackmailed, or some sort of operative who had managed to gain really high-level access.

DANIEL: Or Donald Trump.

BEN: It was in fact a 21-year-old National Guard airman who was sharing these secrets on a Minecraft Discord server…

HEDVIG: Minecraft?

BEN: …for clout, because he was like, “I have uh 💅 code word clearance.” They were like, “Whatever.” And someone called him a cuck. And so, to prove his alphadom, he started sharing military secrets!

HEDVIG: Oh, my god.

DANIEL: Nice going.

BEN: Oh, you cannot make this shit up.

HEDVIG: That’s so funny.

DANIEL: He’s military. So, he’s going to be locked away for so many years, it’s not even going to be…

BEN: Obviously, the wider implications of this are super complicated and I don’t want to make light of the fact that there’s human lives that are legitimately in danger, and this person has done something really not good in a lot of ways. So, I don’t want to make light of any of that. The hilarious thing is how tragically white and male and young this human was as the reason for sharing military secrets. Oh! I weep for my race and my gender. I truly do.

DANIEL: Invisible internet points are invisible. Let’s see. How do I get back to the main thread? My eternal question.

BEN: So, that was in the news. Is there anything else that’s been in the news, Daniel?

HEDVIG: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Yeah. I would like to nominate “to snowden” as a word of the week. To wreck your life by stupidly and narcissistically sharing information. Heyyy, is everyone enjoying the Discord, by the way? Every once in a while, I see you two pop in.

BEN: Yes.

HEDVIG: Yeah, I like it.

BEN: I should pop in more.

HEDVIG: We have so many people there and they post lots of things. And because I’m in a different time zone than some of them, I wake up and it’s like 20 messages and I’m like, “I love all of you.”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: “I have lost the track of what’s going on, but I’m very happy.” And then, I post something and then they… No, I like it. I like it. I just get a lot of messages.

DANIEL: It’s true.

BEN: Do you not like it, Daniel?

DANIEL: I really enjoy it, and I don’t mind scrolling through all the messages. It’s a great resource. People ask questions, people answer questions.

BEN: Is this your super, super high-context-communication way of asking us to be there more? You can be honest.

DANIEL: No. No, it’s not. You can engage. Everyone can engage at whatever level they feel like. If somebody’s a patron…

BEN: I was just checking.

DANIEL: …and they don’t feel like engaging, that’s totally cool. Or they feel like dropping in… Nope! You do what you do because it’s all working.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: Anyway, that’s happening and you’re invited. So, that’s patreon.com/becauselangpod.

BEN: Hey, Daniel?

DANIEL: Yep.

BEN: In addition to truly baffling military secret news, [HEDVIG LAUGHS] is there any other news from the world of linguistics in the week gone past?

DANIEL: Nope, but…

BEN: Cool.

DANIEL: …I think we should just jump straight in.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Wicked. You can even leave this bit in. This is a great segue. Fuck the news, because we got a Mailbag episode to do.

DANIEL: All right.

HEDVIG: The vibe today is fun.

DANIEL: Here we go. Oh! And our first question is about “Here we go.” [BEN LAUGHS] So, this one’s from John via email, hello@becauselanguage.com. John says, “Here’s a language question I’ve been wondering about for a long time. Why do we use the words, ‘Here you go’ to mean: here’s the thing you just asked me for? When someone across the dinner table asks me for the salt shaker, I hand it to them and say, ‘Here you go.’ Wouldn’t ‘here it is’ be more appropriate?”

BEN: It would.

DANIEL: Anybody got a broad-level sense of what’s going on here?

BEN: Well, first of all, I would like to give… We need a name or here we go, we’re on linguistics podcast. We’re probably well suited to this.

DANIEL: Here we go.

BEN: We need a name for when a listener asks a question that draws my attention to a thing that has existed in my consciousness for my entire life and until this very moment, I didn’t realise it was weird. And now, it will forever be weird. And it’s true. Why the flip would we say, “Here you go”? It doesn’t make any sense.

DANIEL: No, it’s the same as when PharaohKatt asked us about, why do we say, “You’re welcome”? What’s going on there? And then, we found out lots of cool stuff.

BEN: Okay. So, my guess… No, Hedvig, what’s your guess?

HEDVIG: Well, first of all, GO in English both means like, “I’m going to the shop,” and like, “How are you going?” “How did that go?”

BEN: But doesn’t that mean the same thing, but just in a fairly antiquated sense?

HEDVIG: Oh, does it?

BEN: Like, “How are you going?” is saying like, “How are you proceeding forward through your existence?” That’s how I’ve always…

HEDVIG: Right. But that’s already metaphorical, like you’re not physically moving. You’re referring to some sort of metaphorical abstract, like: how are you progressing through time in your life? Right?

BEN: Right. Okay. Fair fair fair.

HEDVIG: So, that’s already a little bit removed. And then, “How did it go with the talk at the University of the Third Age, Daniel?” Like, “How did that go?” We’re stretching it.

BEN: That’s interesting, yeah. But “Here you go,” is it even stretched even further though, isn’t it?

HEDVIG: Right, because “here you go”… Yeah, because it flipped, because it’s not like, “How did that go?” It’s: I’m observing you’re going, here you go.

BEN: It’s strange, isn’t it?

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: It’s weird.

BEN: If we were to map how central a version of… Would we use the word SENSE? Is SENSE the right word here?

DANIEL: Sense? Yes.

HEDVIG: Sense is good.

DANIEL: Sense is exactly the right word.

BEN: If we were to map the senses of the word GO with the dead center of it being literally to go forward in a literal, physical space and way, “Here you go,” that sense, do we think that would be the most peripheral of all the GOs? I feel like it would be, at least of the ones I can think of.

HEDVIG: It’s pretty far out there.

DANIEL: By the way, I so welcome this because this is a great chance to talk about the grammaticalisation of GO, how it’s gone from — gone! — from just movement to conceptual movement to movement along a path to operation to future marker, like be going to, gonna, right?

BEN: Yeah, these are all…

HEDVIG: I’m gonna go there tomorrow.

BEN: …forms of go, aren’t they?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: They’re all forms of GO. In the OED, the Oxford English Dictionary, there are 603 senses of GO.

BEN: Get. The fuck. Out of here.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: It’s a long page.

HEDVIG: And that’s not even that weird, globally speaking, words of movement have a tendency to move into other senses in totally unrelated languages.

BEN: This is like a panlinguistic thing that we see happen again and again and again?

HEDVIG: Yeah yeah, movement ones, often, specifically, future tense, like moving forward and things happening in the future, a lot of different language communities are like. “Yeah, yeah, yeah. Those are the same.”

DANIEL: Yeah. Like, in Spanish, “voy a hacer algo” — they use the verb TO GO for that as well. Incidentally, 603 senses is not the most that any word has. The most is…

BEN: No, I’m sure it’s not the most, but it must be up there, right?

DANIEL: It is up there. The most is 654, and the word is RUN, another verb of motion.

BEN: Ah, there we go. Hey, give us the top 10 right now. Are most of them movement?

DANIEL: I have this kind of weird list from insider.com. I don’t think it’s the best, but it’s the first one I could find. It’ll be in the show notes for this episode, becauselanguage.com. According to this list, here are the words with the most senses. RUN with 645, GO has 600 and… what did I say? 630.

HEDVIG: Uh-huh.

DANIEL: SET has 430. TAKE, 343. STAND. GET. Oh, GET is huge. I can’t believe that GET doesn’t have more.

BEN: So, the point is though, nearly all of those are movement and physicalisation.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Because they are so versatile.

BEN: Yeah yeah yeah.

DANIEL: So, the OED has a blog entry about GO, and they identify three paths for GO words, and one is movement, but nonspecific, not saying where from or where to, just moving. That’s where we see things like, “Let’s go,” or, “How did it go?” Also, things that are functioning like, “This clock doesn’t go,” or, “The wind goes [MAKES WHOOSHING SOUND]”, that kind of thing. Branch two is movement away from something, specifically away. So, you say things like, “She’s gone,” or, “It’s gone out of my mind,” or, “An avocado goes for a dollar these days,” that kind of thing.

BEN: Mm. Okay.

DANIEL: And then, branch three is movement toward. So, the three branches are movement nonspecific, movement away, and movement toward a place or a concept where you GO TO BED or you’ve GONE MAD. Or, I say, “Don’t go changing to try and please me.”

BEN: Don’t go chasing waterfalls.

DANIEL: Stick to the rivers and lakes you’re used to.

HEDVIG: I suspect that “here you go” is the third one, movement towards.

DANIEL: Why do you think that?

BEN: Well, it’s both, isn’t it? If you’re passing something to someone, “Here you go,” is away from you and towards them.

DANIEL: I was going to say 2: away from.

HEDVIG: But I’m sorry, English doesn’t have a different word for YOU, whether it’s a subject or an object, like, “You love me, I love you.” So, you don’t know what the YOU one is, and I interpret it as… because you’re handing them the salt, you’re moving the salt towards them.

DANIEL: Yep. I was going to say not just nominative, not accusative, I was going to say dative, because, “Here’s the avocado.” You’re selling it to them or you’re giving it to them, and you say, “Here to you it goes.”

HEDVIG: The avocado goes.

DANIEL: “Here you go,” that kind of thing.

BEN: What about if it’s a usage one? Like, goING. So, follow me on this logic. “Here you” and then the “go” refers to the fact that you’re going to be using it. So, like, “Here, YOU go.”

DANIEL: Maybe.

HEDVIG: Oh, you have a go.

BEN: Kind of! That sort of thing. Here you go, basically, you’re saying like, “Here, you’re now going with the thing.” It’s your go with it or whatever.

DANIEL: Yeah, you give somebody something and then they go away, right?

BEN: Oh, man, [DANIEL LAUGHS] this is so dense!

DANIEL: I think I need to do a little bit more research on how exactly this evolved. I did… I found a few things. So, people didn’t used to say HERE YOU GO. They used to say, “Here you are,” or, “Here it is” in the 1800s. We do see the expression, HERE YOU GO in the 1800s, but it’s more like, “Look at you doing something silly.” In 1852, we see, “Where are you going, Billy? Come back with you. It’s after school time now. And here you go with a spade over your shoulder.” And here you go doing…

BEN: Oh, yeah. Okay.

DANIEL: “Here you go doing this dumb thing that you are going to do.”

BEN: It’s definitely, you’re moving away.

DANIEL: That’s right. But by the late 1800s, then we start seeing the HERE YOU GO as in this is for you. By the way, this is from the wonderful Grammarphobia Blog by Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman. Link on our website, becauselanguage.com. ‘”You’ve both won the heat, race, and money. Here you go,” and he tipped the two lads handsomely.’ That’s from 1879.

HEDVIG: Oh.

BEN: I wonder if it’s just, again, I’m going to ask the question, would this be semantic drift? So, in the late 1800s, you were talking about, “And here you go with a spade in your hand.” And then, because that was getting said a bit, it morphed into a placeholder for “Here it is,” or, Here is the thing that you want,” or, “Here you are.”

DANIEL: It’s a good example of semantic drift. Also, a great example of what’s known as semantic bleaching or grammaticalisation, where it no longer means GO at all.

BEN: Yeah. Well, that’s probably… if we had to land anywhere, I’d say, that’s the most relevant answer to John.

HEDVIG: But that’s just the first step, right? And GO doing things that aren’t physical movement, we got… that one happened long before, we got anywhere close to HERE YOU GO right?

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. That’s right.

HEDVIG: It’s like, “How are you going?” blah, blah, blah, already happened before that. So, then we get a path from those metaphorical usages to HERE YOU GO, which sounds like it’s… through that one, I like the example with a race car, like, “Here’s your money, here you go.” That’s the most clear example of, like, you’re welcome.

BEN: Do we want to put a pin in this and basically be like, “There’s more mystery here than we anticipated,” and then we can come back to it?

DANIEL: I would like to track it, because right now, the most likely path to me seems like branch two of the OED’s definition of GO: movement away. I give you a thing. It goes away from me… here to you it goes. So, here you go.

BEN: So, essentially, we’re detectives on the case and we’ve got some clues, [HEDVIG LAUGHS] but we don’t have conclusive proof.

DANIEL: No, but we do know that it seems to come up at the end of the 1800s and persists today.

BEN: Okay. Good clues. Good clues. All right, the case is hot.

HEDVIG: We will get to the bottom of this, Ben, but you have to also remember that ~we might never know~.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Linguistics is in that wonderful midground between hard science and airy-fairy nonsense like psychology.

DANIEL: Well, we just have to bump into the right references, you know? True about psychology though.

HEDVIG: Yeah, it’s hard.

BEN: [LAUGHS] Sick burn.

HEDVIG: Sometimes, we can learn more about changes in one language like English by studying changes in other languages. So, we’re like, “Oh, all languages seem to sort of do this thing.” For example, the word BABY meaning things that are small. Meaning, things that are trivial. Meaning, things that are blah blah blah.

BEN: Buckarino.

HEDVIG: Buckarino.

DANIEL: Thanks, John, for that great question. We’ll be updating as soon as we can. This one from Vehemently via email. “Hi, lingos. I’m not sure if this is Word of the Week material, as I don’t know the standards.” Pretty high.

BEN: [LAUGHS] It’s so low. So low, Vehemently. So very low.

DANIEL: We try to keep ’em up! “But I’d like to express some affection for the common transformation of the English word “something” into sumpin’.”

BEN: Sumpin’.

HEDVIG: Sumpin’. Yeah, sumpin’.

DANIEL: Sumpin’.

BEN: So good.

DANIEL: “I just find it utterly delightful,” says Vehemently, “that we can manage to shrink a word down to half its size and still be able to use it in the exact same way. To turn this into a question, do you lot have any favorite ‘debuccalisations’ as I’m told they’re called whether in English or any other language? Nowadays, anytime I hear sumpin’, I’m reminded of the ingenuity of humans and smile a bit. From Vehemently.” Ooh.

BEN: Okay. So, first things first, unbuccalisation… Sorry, debuccalisations.

DANIEL: Debuccalisation is what you do when you have to pee.

BEN: Awesome. This is a great word. I just like saying it. This is like the word SYPHILIS for me. I don’t care what it means. The word itself is delightful. Syphilis. Debuccalisation. It’s so good. It’s such a good word.

DANIEL: Debuccalisation.

HEDVIG: So, back to debuccalisation. I’ve never heard that term before. Thank you so much to…

HEDVIG and BEN: Vehemently.

DANIEL: I used to trip over this term a lot in my linguistics history and I would keep forgetting what it meant.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah? It sounds like it means removing consonant stops. No?

DANIEL: No.

HEDVIG: Oh, fun.

BEN: Brrr! [BUZZER]

DANIEL: The BUCCA in debuccalisation, it’s your mouth. So, Spanish BOCA, French BOUCHE.

HEDVIG: Oh.

DANIEL: It’s the process of removing a sound that was… taking a sound that is usually pronounced in your mouth and unmouthing it. That means pronouncing it maybe with your pharynx, maybe with your glottis. That means glottal stops, as in UH-OH. That’s the sound in the middle of UH-OH. And it also means /h/, the h sound, because that’s not produced with our mouth either. That’s glottal as well. Way down there.

HEDVIG: Right. So, that just sounds like glottalising.

DANIEL: It is, but it doesn’t have to be your glottis. It can be your pharynx or other places that aren’t in your mouth as well.

HEDVIG: Okay.

BEN: So, taking a mouthy word or a bit of a word that is in the mouth, and chucking it back in the throat.

HEDVIG: De-oralisation.

DANIEL: Ooh, yeah. There we go.

BEN: De-oralisation.

DANIEL: There we go.

BEN: That is so much worse a word than debuccalisation. [DANIEL LAUGHS] I’m sorry.

HEDVIG: It’s my job here to say the worst things.

BEN: Just to drag it down.

DANIEL: So, when we say SOMETHING and we say /sʌʔm/,…

HEDVIG: /sʌʔm/. Yeah.

DANIEL: …what we’re doing is we’re taking that part of the word and we’re glottalising it with a glottal stop: /sʌʔm/.

HEDVIG: Here’s the time to… it’s worth remembering that language isn’t about optimising… It’s optimising several things at once and nothing at all at the same time, right?

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s right.

HEDVIG: And the truth is that when you say the word something, if you say the full word, you’ll be like, “Oh, SOME and THING, it’s SOME-THING,” blah, blah, blah. You can maybe understand it. But when you’re speaking to people, you can probably shorten it and people will understand it, because there’s nothing else to confuse it for, like you are not getting confused.

BEN: Yeah, like GONNA and WANNA and all those sorts of things, right? Very few people say, WANT TO and GOING TO. That’s not how we talk.

HEDVIG: Yeah. And even when you get linguistic change, where you do get two forms starting to sound a bit alike, you need to ask yourself, “Are they occurring in the same context so that you could get confused?” Because, like, the word BANK of a river and BANK that you put your money into are the same, but, like, no one’s ever going to mix them up. In the case of /sʌʔm/, no one’s confused. And I really like /sʌʔm/. I think it’s really good. I don’t have another favorite debuccalisation. Maybe… maybe I do. There’s a thing in American English primarily, but also other ones where when you have words like DON’T or CAN’T…

DANIEL: Uh-huh.

HEDVIG: …often American English speakers drop the T entirely.

DANIEL: I don’ wanna.

HEDVIG: Don’ do that.

DANIEL: Don’ do that.

DANIEL: Don’ do that.

DANIEL: I’m getting a glottal thing off of that. Yeah, that’s it.

HEDVIG: Yeah. It’s like a little thing, which in the case of DON’T…

DANIEL: Can’ help it.

HEDVIG: Can’ help it.

DANIEL: We can’ help it.

HEDVIG: Which in the case of DON’T is fine because the affirmative, the positive is DO. “I do want to,” “I don’ want to.” But with CAN’T…

DANIEL: CAN /kœn/ and CAN’T /kœnʔ/.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] It’s hard.

HEDVIG: You now have CAN /kœn/ and CAN’T /kœnʔ/.

BEN: Yeah, you can’ have it. Can’ have it.

DANIEL: The way that I would always teach my English students was that CAN is just /kn/, it’s not stressed, but CAN’T, /kœnʔ/ is stressed. So, you say, “I can’t help you,” — it gets the stress — “I can /kn/ help you.””

BEN: True. Yeah, because we’re all going like Deep South on this. [LAUGHS] This is not just Americanisation. It’s like, “You can’ /kœnʔ/ have it, you c’n /kn/ have it.”

DANIEL: I can’t /kœnʔ/ help ya. I can /kn/ help ya. I can /kn/ help ya. I can’ /kœnʔ/ help ya.

BEN: Yeah. So, it ends up being really different, because you drop a vowel out of the affirmative.

HEDVIG: You say really different. But the second language learners, we learned that there’s a T there. That’s not there.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Hang on.

DANIEL: Oh, there’s no T!

BEN: Hang on. What is absolutely not in question here is the bullshit nonsense, fucking vagaries that is the English language, right? [DANIEL LAUGHS] That is absolutely the case. No question.

DANIEL: It’s just language. It’s just language!

HEDVIG: English is fine. You need to tell the rest of us that’s what you’re doing. So, when we learn it…

DANIEL: Exactly.

HEDVIG: …when we come to your country, we need to be like, “Oh, someone needs to be like, PSA, everyone. Sometimes, there’s this… [CROSSTALK]

BEN: A good English teacher does that though.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

BEN: That’s the thing.

DANIEL: ~I certainly did.~

BEN: We’ve seen TikToks of people like this, right? People from language backgrounds other than English who are themselves English teachers, and then doing that really fun thing of like, “I’m going to teach you all the real rules.” And then, they say stuff like this, right?

HEDVIG: Oh, yes. I’ve seen those.

DANIEL: Yeah.

BEN: It’s just like, “You don’t say you can do something. You say you can /kn/ do something.” Did you see how it was a K and a tiny N? Kn, kn. That’s how you do things. You /kn/ them.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Well, I also have my favorite debuccalisations from other languages.

BEN: Oo, yes!

DANIEL: For example, in Ancient Greek, have you ever wondered why HEPT- and SEPT- alternate? You can have a HEPTATHLON, but you can’t have HEPTILLION things. It needs to be SEPTILLION?

BEN: That is true.

HEDVIG: September.

DANIEL: And also, you can have a HEXAGON, but you can’t have a SEXAGON because that would be something that a SEXTET would do, but not a HEXTET.

BEN: Oh.

DANIEL: Well, Ancient Greek had a pattern where S debuccalised to H, which explains why we have serpents. But when you study serpents, you’re studying…

BEN: Herpetology.

DANIEL: That’s the same word.

BEN: Oh, get the flip out of here!

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Yep.

BEN: That’s so cool!

DANIEL: Another one in Proto-Indo-European, they also had a K to H thing. So, Proto-Indo-European, ḱm̥tóm meant 100. Latin just stayed CENTUM. Then, German came along with HUNDERT, and then English went with HUNDRED. So, that’s why we have centuries, but also hundred. They’re related. And another one, in Proto-Indo-European, KAPUT was your head. Kap, kaput. And Latin would keep that as CAPITA. But German wasn’t on board with the change. It stayed as KOPF. It didn’t move to H. But then, English went full debuccal with HEAD. Which tells me that debuccalisation from K to H had only partially happened in Proto-Germanic.

HEDVIG: Oh, fun.

BEN: That is really interesting.

HEDVIG: My cat distracted me a bit, so I need a reminder of why reptilians are associated with the number seven.

BEN: No, serpent. SERPENT and HERPETOLOGY.

DANIEL: Because of the S to H thing.

HEDVIG: Oh. okay. Good. Sorry.

DANIEL: Also in Spanish, they’ve got an S to H thing. A lot of people say the word for SAME, which is MISMO. MISMO. They often say it /mihmo/. It’s the same to me, me da lo mihmo. So, that’s an example of debuccalisation. And the reason why we’re able to do this and still understand each other is because our brains are just churning away. When we hear stuff, we’re always predicting, predicting, predicting, guessing what’s going to happen and we kind of already know as soon as somebody starts a hentence, [CHUCKLES] what’s going to happen at the end of the hentence.

BEN: Ah, I see what you did there.

DANIEL: So, our amazing prediction skills make debuccalisation possible.

BEN: I would also like to mention, just because this little question had me thinking about contractions, and abbreviations, and things getting shorter, and a little bit simpler, and easier, and that sort of thing, it reminded me of the great standup routine by Gary Gorman about how all the American states got their two letter abbreviations, which is phenomenal. It’s really on brand for our audience. So, if you haven’t seen it, which I’m sure most of you have, if you’re at this show. But if you haven’t, there will be a link in our show notes page. [WHISPERS] Daniel, I’ve just put the link in the Discord server.

HEDVIG: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Thank you. I will slap that up. And thank you, Vehemently, for that great question.

BEN: That was a great question, Vehemently, because I learned a word, debuccalisation, and I’m just going to say it with no context. It’s good.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Let’s go on to Related or Not, our favorite game.

HEDVIG: [GASPS]

BEN: [EVIL LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: This game is brought to us by our Discord pal, Old Anne, who’s given us two pairs of words. The fun thing about this is I didn’t know which ones were right and which ones were wrong. So, I made some guesses before looking it up.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah?

BEN: So, you’re in on this as well?

DANIEL: I’m playing too!

HEDVIG: Competing.

BEN: So, here’s what we do. You give us the things, we place our bets, and then you tell us what the house bet.

DANIEL: Okay. And by the way, sorry, for anybody who doesn’t know, this is where we give pairs of words and you have to guess whether they are related or not, or is the similarity between them merely coincidental. Okay, here’s the first pair. FAULT, like, “It’s your fault.”

HEDVIG: Oh.

DANIEL: And FALTER.

HEDVIG: Oh!

DANIEL: If I waiver, if I halt, if I stop. If it’s my FAULT, do I FALTER? So, are those two words related or not?

HEDVIG: I thought you were going to say FAULT, as a geological FAULT.

BEN: I thought that as well.

DANIEL: That’s a good question of its own. While you two are guessing, I’m gonna be looking that shit up.

HEDVIG: Like a fault line.

BEN: Shelve that! Not now, Daniel, we’ve got shit to do!

DANIEL: Oh, come on!

BEN: I’m going to jump in on first on this one and, Hedvig, you can have your first crack on the next one. How does that sound?

HEDVIG: I’m in accordance.

BEN: Okay. I have your accord. I’m going to go not related, and I’m going to guess they’re not related because I think FALTER sounds suspiciously like HALTER, and that makes me think of bridles and other instruments and accoutrement for animals, and animals of burden and that sort of thing that might fall, or trip, or that sort of stuff. So, I think FALTER comes from a different backstory.

DANIEL: Once you find out about debuccalisation, you just apply it everywhere! My goodness.

BEN: /falʔa/! /falʔa/.

DANIEL: Okay, very cool. So, not related for Ben. Hedvig, your guess.

HEDVIG: I think they are related.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: I think to be wrong and to fall.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Yep. Yep, yep!

BEN: What is falling, other than being wrong with your body in existence?

DANIEL: That’s right. You did something wrong. You stepped wrong.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: And you might have done so because of an earthquake nearby. Who knows? You know? They’re all related.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Okay. What did the house bet, Daniel?

DANIEL: My guess was no. I thought that FAULT was from French because of the spelling. And I thought that FALTER might have been… Actually, Ben, I guessed the same exact thing as you. I thought maybe FALTER was related to Latin for HALT, because at least in Spanish, there’s an F to H thing going on. I thought maybe there was for this one too.

BEN: You’ve got really smart linguistic reasons to do it. I just thought about horsies!

DANIEL: Well, we took the same sonic path.

BEN: True.

DANIEL: Okay. So, Ben and I think, nope, they’re not related. Hedvig thinks yep, they are related. The answer: they’re not related.

BEN: Yes.

HEDVIG: Fuck off.

BEN: Come on!

DANIEL: So, FAULT comes from old French FAUTE. It didn’t have an L. It’s related to FALSUS [Latin], but it dropped the L pretty quickly. By the way, FAULT is related to FAIL, interestingly.

HEDVIG: There we go.

DANIEL: But FALTER is of unknown origin, maybe from a Scandi language or could have been from a Middle English FOLD, and then you add the -LE or the -ER to say that you’re doing it over and over again or doing it very intensely. The OED says that FALTER has always been written with the L and FAULT wasn’t. In fact, until the 1500s, it didn’t have an L and nobody said it with an L. You would say that it was your FAUT.

BEN: There we go.

DANIEL: That’s one.

BEN: One to Ben.

DANIEL: Second word. SPADE and SPATULA.

BEN: SPAYED, as in what we do to cats, or SPADE as in what we dig in the ground with?

DANIEL: Digging in the ground like a shovel.

BEN: But not the same as a suit of cards? Or is that the same word?

HEDVIG: That’s the same.

DANIEL: I think it is actually the same for that one. Yeah, because it looked like the shovel thing.

HEDVIG: Looks like a shovel.

DANIEL: So, SPADE, the shovel thing and SPATULA for spreading frosting on cakes.

BEN: I want it known that obviously a SPATULA is the thing that you flip eggs with, not the thing that you spread.

DANIEL: Oh, no, we’ve got semantic variation! Okay.

BEN: Yes, we do, sir.

DANIEL: What you’re talking about, Ben, is a turner, a flipper.

BEN: Oh, [BLOWS A RASPBERRY]

DANIEL: A turner or a flipper, you have to choose one of those two.

[DANIEL EXITS]

HEDVIG: Oh, god.

BEN: Jesus. I’ve heard people call it an egg flip and I’m like, “Yeah, okay. Egg flip.”

[DANIEL COMES BACK WITH RUBBER SCRAPER]

HEDVIG: I am always confused by SPATULA in English because that…

BEN: No, Daniel, no.

HEDVIG: You’re gonna enjoy the Swedish word for this.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: This.

HEDVIG: The Swedish word for that object that Daniel is holding, which some people call SPATULA in English is SLICKEPOTT, which means lick-bowl.

BEN: Yes. I love it. I love it so much more than what Daniel’s just appallingly calling that thing.

DANIEL: Slickepott?

HEDVIG AND BEN: Slickepott.

DANIEL: Licky pot.

HEDVIG: Slickepott.

DANIEL: Okay. I’m going with the pot.

BEN: Like lick the pot.

DANIEL: Yeah, naturally.

HEDVIG: Yeah, you use it to lick the pot after your mom’s baked things.

DANIEL: Hand me the lickepott.

BEN: I like that a lot. That’s what I’m calling it from now on, and I will continue calling the thing that you flip food with in a frying pan a spatula, ~because that’s what they fucking are~.

DANIEL: I’m going to use a shovel.

BEN: Anyway.

DANIEL: Yes or no?

BEN: Oh, no, sorry. Hedvig, you first.

HEDVIG: [MUSING] Spatula, spade. Spatula, spade. Spade, spatula. Spatula, spade. Spade. Spatula. Spa… Spa…

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] The way we play the game is not to repeat the words in an increasingly agitated fashion.

BEN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, this does not make for a good podcast.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: No, but I’m just thinking…

DANIEL: It could be a good promo.

HEDVIG: …the spade, dah, dah, dah, and spat, yula, D and T.

BEN: Ooh.

HEDVIG: Super similar stuff. A lot of similarities. But is that meant to be a red herring? Am I meant to be confused?

DANIEL: I have no idea. I haven’t looked it up yet.

BEN: Hedvig, we’re getting perilously close to you at a board with photos and red twine. You’re gonna have to make a call here.

DANIEL: No, I think she’s playing for time.

HEDVIG: I think they’re related.

DANIEL: Okay. That’s your answer?

BEN: Okay. Hedvig’s gone with yes. Not to be oppositional, because that is not my way. My gut was no. I don’t know why. So, now I’m going to post hoc an explanation. I don’t think SPATULA is an older word than SPADE, just intuitively. I feel like SPADE is a much older word than SPATULA. I don’t think a word is going to become more complicated as it, like, shifts domains the way SPATULA has.

DANIEL: …Can do?

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: Erosion is not the only process here.

BEN: Fuck. Well, then I’m probably going to be wrong. I’ve already staked my claim. I said no. I’m sticking to it.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: It could be that the -ULA thing is a diminutive suffix, like a small spade.

DANIEL: That’s what I thought. That’s exactly what I thought.

BEN: Okay. So, Daniel went with yes. He thought it was a diminutive form of spade.

DANIEL: I went with yes and I thought that -ULA was a diminutive.

BEN: Okay. Oh, noticed the past tense there. Ooh.

DANIEL: Two yes votes, me and Hedvig, and one no vote, Ben. Answer: yes, they are related.

HEDVIG: Yay.

BEN: Fuck!

DANIEL: Whoo-hoo.

BEN: For the reason you suspected? Is it just like a spadino or a spadito?

DANIEL: That is correct. -ULA is actually the diminutive.

BEN: From what language?

DANIEL: They both come from Proto-Indo-European “*spe-dh-“, but they took a slightly different path. SPADE came through Proto-Germanic SPADEN, and then down to SPADE. That was pretty simple.

BEN: Because we’ve been digging in the dirt for a real long time.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: That’s a thing that we’ve done a lot of.

DANIEL: And SPATULA came a slightly different way. Latin, SPATULA. It just really was that way in Latin.

BEN: As in for a spade. That’s what we called a spade.

DANIEL: Yep. It came, in turn, from Greek “spatha.” The -ULA is diminutive of SPATHA broad, flat tool, or weapon.

BEN: Okay. So, if I’ve got this right, in Greece, SPATHA was a spade, like a thing you dug in the ground with or a thing you hit things with or whatever, a bladed thing.

DANIEL: Yep.

BEN: But then in Latin, it acquired the diminutive, although it still referred to the same tool.

DANIEL: I think they might have used smaller ones. I think that there is a reason [BEN LAUGHS] why they used it for smaller. They had big ones and small ones, right?

BEN: There was a slightly more European bent to the Italian ones, darling. [DANIEL LAUGHS] They were just a little bit more svelte, a little bit nicer.

DANIEL: Mmm! The really cool story here is about SHOVEL though, because I got curious about SHOVEL to see if that was related, and I found out that it’s called a SHOVEL because you…

HEDVIG: Shovel.

BEN: Shove stuff with it!

DANIEL: You shove stuff with it.

BEN: Ah. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: The -LE on the end is good old instrumental -LE. Meaning, you use this thing to do that thing. So, you use a spindle to spin.

BEN: Like you YODEL.

DANIEL: I wasn’t thinking of YODEL.

BEN: Is that not right?

HEDVIG: HANDLE.

DANIEL: You use your hand to hold a HANDLE, use a spindle to spin, you use a GIRDLE to gird your loins, and you use a shovel to shovel thing.

BEN: I’m going to put YODEL in there, because what do you do when you yodel, you go YO!

DANIEL: That might not be instrumental. That might be frequentative.

BEN: Oh, just give it to me, Daniel.

DANIEL AND HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: Because -LE has lots of uses here. So, that’s a yes. So, congratulations to both of you for getting at least one right.

BEN: Draws. Everyone’s least favorite end to a competition.

DANIEL: While we’re here, Dan asks about MANUFACTURE. “I was blown away to discover that FACTORY and MANUFACTURERS do not have common etymology based on my rudimentary searching, but I could be wrong. This came up when our D&D DM said MANUFACTORY and I ended up down the rabbit hole.”

BEN: [LAUGHS] Oh, that sounds like my kind of D&D game.

DANIEL: Yeah, exactly.

BEN: When the DM says something, and you’re like, “Actually, I think that you’ll find the etymological roots of those two words you have combined are in fact quite different.”

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES] They are distinct.

HEDVIG: So, first of all, MANUFACTURE surely has to do with HAND and MAKING.

DANIEL: The MAN is not a man, but it is a hand.

HEDVIG: Hand?

DANIEL: So, it’s related to manual as in manual labor. Correct. And the FACTURE?

HEDVIG: Doing.

DANIEL: Yes, it is the…

HEDVIG: Like Latin Romance root for DO.

DANIEL: That’s right. FACERE, to do or to perform.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: It turns out that FACTORY actually is the same. Dan didn’t quite get that one right. It comes from also FACERE, to do or to perform, which then got down to us through late Latin FACTORIUM. So, the FACT in both is related, but the real story here is what MAN has gotten up to. Lots of words relating to your hand or to power or to force. Like, you MANAGE things, you can have a MANDATE, you can even wear MANACLES.

BEN: Oh, that is interesting. Wow.

DANIEL: And you can manufacture. With your hands.

HEDVIG: Do things manually.

BEN: There we go. So, they are in fact related. They do come from a common root.

DANIEL: These two are in fact related. So that was fun. So, thanks to Old Anne and to Dan for giving us some great fodder for our games.

BEN: Ah, what’s next?

DANIEL: This is a question from Prunted Drinkulo on our Discord. “Have you ever done something about the double IS phenomenon in English? I’m not a native English speaker. I’m from Germany. So, it really irritated me when I started noticing a lot of IS-IS-es in podcasts and videos. But only after I heard someone saying IS WAS, I started googling because that makes it obvious that it’s not just a stutter. I found this site about it and there’s a link to the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project. From my very bad sample, I have the feeling this is getting more and more common. It seems to have started after noun phrases, like, ‘The problem IS IS,’ or, ‘The thing IS IS.” But I also heard a lot of sentences like, ‘What I can actually start doing IS, IS that,” or even, “My feeling at the time WAS IS,” dah, dah, dah, dah. Okay. So, what’s your feeling, folks? More common, less common? Are you noticing this?

HEDVIG: Wait, first of all, I’m not even sure what it is yet, because there’s one thing where people are just retaking the sentence. “The problem is, is that I don’t really like green.”

DANIEL: Yes.

BEN: Right. So, it’s almost like a word that is acting like a comma. Like, you pause and then you resume, but you resume a little bit further behind.

HEDVIG: That’s not like… when people do that, I take that as like: they’re doing a retake. They’re doing a pragmatic conversational thing because they did a little pause or something. That’s not the same as…

BEN: Can we give this a word?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay, Ben.

BEN: I’m sure it has a linguistic word. Can we give it a much funner word?

HEDVIG: Yes, yes, always.

BEN: So, this is a Hong Kong Kung Fu sentence.

HEDVIG: Oh my god.

BEN: Wait, follow me on this one. In Hong Kong kung fu movies, when you do a fight scene… So, think of any Jackie Chan film, a good one you’ve ever seen, right?

HEDVIG: Yeah, I know what you mean.

BEN: Whenever they do a hit, to sell it, you see it two or even three times. Right? You see it from one angle, and then after the cut, you actually see the hit again just a little bit, because it really sells the hit. And I think that’s kind of what’s happening here, because you don’t pause in a weird place, you pause at the point in the sentence where the key information is going to start coming, and then you go back just a tiny bit to, like, sell it.

DANIEL: Hong Kong Kung Fu sentence.

HEDVIG: Yeah. Speaking, making sentences is very hard, and especially, the longer and more complex they are, you’re probably constructing them on the spot while you’re speaking. And that’s hard. So, we do all kinds of pauses and retakes and repetitions. You might have noticed [BEN LAUGHS] that certain people have certain fillers. Like, I was reminded that Ste’s supervisor from Australia — he came to visit recently in Germany — his filler is “You know.” And oh, my god.

BEN: It drives you up the wall? [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Sometimes, yes.

DANIEL: Why would that drive you up the wall? YOU KNOW is fine. He’s building consensus. Reducing distance.

HEDVIG: The message that we got from this, I believe nonnative English speaker from Germany is that they heard this a lot. There’s only some examples. So, “The thing is, is,” “What I can actually start doing is, is that,” and all of them to me sound like you need a break. Am I wrong?

DANIEL: “What I can actually start doing is, is that…” I think you would put a break there.

BEN: Yeah. Even his last example, or sorry, their last example, because I’m not sure of the gender of this person.

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES]

BEN: “My feeling at the time was, is this…?” they stop at “is” but you would presume that there will be something that follows on.

DANIEL: Oh, I need to know the next word because, “My feeling at the time was, is he a monster?” That would not be the double IS. But if they said, “My feeling at that time was is that…”

BEN: Oh.

DANIEL: That’s a little different.

BEN: It is a little different.

DANIEL: But you know what? I don’t want to get hung up on that.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, fair enough, fair enough, fair enough.

DANIEL: Let’s talk through what’s happening syntactically. We have these things in English called clefted sentences. Instead of saying, “He is a monster,” I can say, “What he is, is a monster.”

BEN: Is a monster. Yeah. [LAUGHS] That is definitely a kung fu movie sentence, right? That is you deliberately stopping and then going back a second to really sell the hit.

DANIEL: No, it’s not, because what you need… like, if I say, “What this is, is a disaster,” so now “What this is” functioning as a subject. It needs a verb and that’s the second IS. “What this is,” that’s my subject, “is a disaster.” So, now I’ve got a full sentence with one verb. Two clauses, but one sentence.

BEN: I still feel like this is a kung fu sentence. You overlap a crucial bit, and it happens twice.

DANIEL: All right, well, hang on, just to bring home why this is a different kind of thing. I’ll drop one IS.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: “What this is a disaster”

BEN: No, but you’ve got to put the pause in there. “What this is…?

DANIEL: “What this is, a disaster”

BEN: A disaster. Yeah, you’re right. It doesn’t work. It doesn’t work.

HEDVIG: Wait. So, instead of a kung fu sentence, it could be just like Daniel is saying that the first thing is the whole nominal phrase. “What this is” is the whole noun phrase?

DANIEL: That’s right. That’s a noun phrase all by itself.

HEDVIG: “What this is, is a disaster.” You can still do a break in between there, but that could just be a break between a noun phrase and the next phrase.

DANIEL: Yeah, it doesn’t work if I drop one IS. “What this is, a disaster.” I’m missing a verb. You need one.

BEN: You’re right. Now, you’ve convinced me. That makes this not a kung fu movie sentence is because in a kung fu movie, if you don’t do the double hit, it still works. It doesn’t look very good.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s right.

BEN: Whereas this, it doesn’t work. It breaks.

DANIEL: Okay. Now, once we get these kind of sentences, like, “What this is, is a disaster,” then we could start doing similar sentences and we start seeing things like, “What I mean is, is that we like pickled beets.” Now, that’s a little bit different, because here the subject is “what I mean.” It doesn’t need an “is,” but we do it anyway.

BEN: So, maybe that’s a kung fu.

DANIEL: Now, that’s a kung fu sentence. If we don’t do that, if we don’t add a double IS, sometimes it seems weird. I’m reading a Slate article by Alyssa Pelish. Patrick McConvell at ANU, a linguist, and Laura Michaelis-Cummings found experimentally that if you don’t have that extra IS, it sounds kind of weird. Like, if you don’t have a break, it sounds awkward. And so, maybe — they think — that double IS was a workaround that allowed speakers to avoid that odd sound.

HEDVIG: Right.

DANIEL: The link that Prunted Drinkulo added from the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project — link on our website — says double IS well attested in contemporary American English as well as in Australian and New Zealand English. Anne Curzan’s analysis of The Corpus of Contemporary American English suggests that this construction first appeared in the second half of the 20th century. So, it’s pretty new, but it just allows us to do that extra kung fu hit and makes it seem good.

HEDVIG: Wow.

BEN: I dig it.

DANIEL: But it also sounds like not all double ISes are equal. Right? Some are this construction, and some are other things, some are retakes or something else.

DANIEL: Some are kung fu and some are not kung fu. That’s right.

HEDVIG: They had some sentences here. So, “the problem is, is that you’re always late,” and then one that’s supposed to be bad is, “The question is, is do we have enough time?”

DANIEL: They’re both kung fu sentences.

HEDVIG: Right.

DANIEL: They’re both doing the thing.

HEDVIG: “John is is happy.”

DANIEL: Yeah, that doesn’t work.

HEDVIG: That one’s bad. Right?

DANIEL: Right.

HEDVIG: “The thing is, is going to fall apart.”

DANIEL: The thing is… that’s weird, because it’s got two ISes.

HEDVIG: That’s weird, right?

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s odd. That doesn’t strike me as right at all. I would say, “The thing is, is that thing is going to fall apart.”

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: But I needed to have a special subject in that second clause. Oh, that’s really weird.

HEDVIG: Yeah, but there are some things in this thing that they’ve marked as not right that I think are right. Anyway, it’s right for a variation, apparently. [GIGGLES]

DANIEL: I guess so. We see, THE THING IS, THE QUESTION IS, THE PROBLEM IS. We’ve also seen some weird things like THE REASON BEING, “The reason being is that,” and that makes me think that there’s a being called the Reason Being. “I am the reason being. Hello, I am in this sentence.”

BEN: [LAUGHS] Okay.

DANIEL: There’s also one from 1985. “I made the point once before, is that we have to work on this committee.” So, what I think is happening is that the IS… What I think is happening is, is [LAUGHTER] that the extra IS is functioning like a clause marker. So, “What I think is,” and there’s your clause that’s functioning as a noun phrase, and then IS. I’m waiting for a triple copula. “What the problem is is, is that we haven’t got an idea.”

BEN: Oh, I could see that happening.

DANIEL: That’d be good. I’m waiting for that. Thank you to Prunted Drinkulo for that question. And our last one from Jello for Marcello on Twitter. Jello for Marcello says, “I’ve just noticed to’ve — T-O-apostrophe-V-E, to’ve — as an exclusively spoken contraction as in a ‘list of books I pretend to’ve read.’ Are there any other contractions that appear in speech but just look plain wrong in writing?”

BEN: Oh.

HEDVIG: Plain wrong in writing. Look plain wrong in writing, Jello from Marcello.

DANIEL: Just looks plain wrong.

HEDVIG: That is a problem…

BEN: No, what I think Jello from Marcello…

HEDVIG: …in your head and not with the written. You can make anything feel okay in written if you just put your mind to it.

BEN: Okay. Okay.

DANIEL: It’s true!

BEN: Yes, all right, you radical exceptionist. Exceptivist.

DANIEL: You buckaroo usage expert.

HEDVIG: You are capable of so much.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But, but. But. But.

DANIEL: No, let her go. Let her go. I’m into this.

BEN: Let’s just… I understand that what Jello for Marcello probably meant, not from a prescriptivist “This is bad and we shouldn’t see it.” More just…

HEDVIG: No, I know.

BEN: I think he is being a descriptivist. He’s just phrased it in a funny way.

HEDVIG: I know.

BEN: I’ve also never seen T-O-apostrophe-V-E written down ever before. Ever.

HEDVIG: But now you have…

DANIEL: No.

HEDVIG: …and you love it.

BEN: No! Only because he’s asked… Come on!

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: But now, you have and you love it. Ben, I’m telling you.

BEN: I am with you. Hey, you’re speaking to the person who thinks days of the week should not be capitalised and has been uncapitalising them in all of his shit, and people always give it back and be like, “You haven’t capitalised days of the week.” I’m like, “Because they’re days of the fuckin week! They happen every seven days! We don’t need capitals.” Anyway, point being, what I’m trying to get across here is, I think Jello for Marcello understands that yeah, cool, we could start writing it down, but we don’t and we haven’t been, despite the fact that we’ve said TO’VE of for a really long time probably, but we have written it down for a bunch of other things. I get that. He’s just observed the fact that this thing has missed out on being written down a lot, whereas other things get written down a lot. Are there other things that have also been missed out on being written down a lot?

HEDVIG: So many things! And I think what we’re seeing now with the internet is an explosion of so much more things that occur in spoken language getting transferred to written language, [AGREEMENT NOISES] because people are doing private DM chats and things that… Writing used to be like novels and letters.

BEN: Yeah, it’s true. And you had to look smart, even to your friends.

HEDVIG: Even before that, for the longest period of time, probably most writing was royal decrees and accounting.

BEN: And tax. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: In Latin.

HEDVIG: Yeah, written language has a different domain than spoken, and as those domains are changing, we’re using it more for intimate, informal conversations, we’re going to see more things like this. And Jello for Marcello noted a very fun one that I really like, and I’ve seen other ones. There was one I saw recently…

DANIEL: Yeah. What’s one you’ve seen? Let’s hear it.

BEN: Or heard?

HEDVIG: SHOULD’VE. That one I’ve seen.

BEN: Oh, I’ve seen SHOULD’VE before. Yeah.

DANIEL: I think I’ve seen SHOULD’VE. That’s not terribly uncommon. I haven’t seen THESE’LL, THESE-apostrophe-LL.

BEN: Oh, that’s a fun one.

DANIEL: Anything with these and those, “Oh, you got a headache? These’ll help.” Or, “Flared trousers? Those’ve been out of fashion for a long time.”

BEN: Or those’ll?

DANIEL: Or those’ll.

BEN: Those’ll? I like those’ll.

DANIEL: Those’ll help you.

BEN: Oh, those’ll help. Yeah, get them down.

HEDVIG: I saw a fun one, which I’m not even sure how to pronounce, which is a contraction of there and are. THERE’RE.

DANIEL: There’re.

HEDVIG: There’re. I saw that in Britain.

DANIEL: There’re a few things. Yeah, that’s good.

HEDVIG: There’re a few things.

BEN: For a second, my brain just broke. It literally to the back flip and broke…

HEDVIG: Yeah, I know.

BEN: …because I thought you were talking about there as in T-H-E-Y-apostrophe-R-E. And I’m like, “That very much exists!”

DANIEL: There’s already two of those.

HEDVIG: Yeah, yeah.

BEN: I thought you were saying THEY ARE. And I’m like, “No, what? What is happening?” But you were taking about… Yeah, yeah, I get it.

HEDVIG: No, no, THERE ARE. “There’re many horses in the field.”

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: “There’re many horses in the field.”

DANIEL: The ones that I like are the ones we don’t use anymore. Like ‘TIS. That’s fun.

BEN: ‘Tis is a good one.

DANIEL: ‘Tis true.

HEDVIG: I do use that one. I like it for when people say like, “Thank you for doing that.” And I say, “‘Tis my job.”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

BEN: That’s a good one. That’s quirky. My very favorite and it’s super antiquated and it’s so, so niche is in Australia… Sorry, not just in Australia. In Western Australia, where Daniel and I live…

HEDVIG: Yes.

BEN: …we, as West Australians, conceive of everybody else in Australia as what, Daniel?

DANIEL: Wha… what, Eastern Staters? What?

BEN: Exactly. Thank you very much.

HEDVIG: Oh, you do?

BEN: Exactly.

DANIEL: I guess so.

BEN: Thank you. Because Hedvig has also lived in Australia, so she has just played out a thing that happens to people from West Australia all the time. You go over to an Eastern state or any state other than WA, which is just everything east of us, which is all of them, and you say, “Oh, yeah, it’s good to be in the Eastern states.” And people are just like, “What?”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] I didn’t even know that we said that. That’s just how I mentally conceive of them, as Eastern Staters.

BEN: Eastern Staters, right?

DANIEL: Yeah.

BEN: Okay. So, all of that was preamble, right? How good is this because there used to be a different word for it that was only used by people from WA a hundred years ago. It’s my favorite bespoke contraction.

DANIEL: I feel excited.

BEN: T’othersiders.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Really?

HEDVIG: Oh.

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: Oh, my gosh. T’othersiders. Was this common?

BEN: People from the other side, t’othersiders.

DANIEL: Oh, my goodness. Let’s bring it back. We’ve got to bring it back!

BEN: Yes. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: That’s so good.

BEN: As with the secessionist movement!

DANIEL: No!

BEN: Get these t’othersiders out!

DANIEL: But that’s a Word of the Week. Oh, man.

BEN: From circa 1901.

DANIEL: Gosh.

HEDVIG: Which, sometimes I call Australians and New Zealanders…

BEN: Antipodeans?

HEDVIG: Yes, antipodeans, which literally means opposite to…

BEN: The other side.

HEDVIG: Yeah, but it’s feet, like you’re walking…

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: Oh, yeah. Walking around on the other side of the earth.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Antipodean.

HEDVIG: I said that recently to a Kiwi and she was like, “What?” I said, “You know how antipodeans do blah, blah, blah?” And she was like, “Okay. Didn’t know we were, like, one group.” I was like, “Oh, no, you are.”

BEN: It’s relatively antiquated, antipodeans. It’s the thing that my grandparents would immediately recognise.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: But it’s a good term because very often, Australia and New Zealand share a lot of cultural…

BEN: I agree. Yeah, 100%.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: In the same way that you would say that about Americans, and often what people mean by that is white people from North America, right?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Not exclusively. And certainly, people would then maybe clarify that they’re Canadian instead of American, but they share a lot more than they don’t. Let’s put it that way.

HEDVIG: I was reminded recently that you can say US Americans.

BEN: Say what?

HEDVIG: US Americans.

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: I’ve seen USAians.

BEN: USAians? Oh, I like that.

DANIEL: I’ve seen that one.

BEN: I also recently learned — that’s not the word I’m looking for; I remember being surprised when I learned — that for the French, linguistically, they very comfortably refer to anyone from North or South America as Americans. They see it as like a whole new world bloc, essentially. The Americas, and people from there are Americans.

DANIEL: When I went to Mexico, they said, “Hey, we’re Americans.”

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: These are Mexican people.

HEDVIG: I have this variation too. I have both of those senses, which is why I like US Americans, because they’re more specific.

BEN: But we should also acknowledge calling the whole lot of that shit after some Italian doofus, probably not a great practice.

DANIEL: Well, thanks, Jello for Marcello, for that question.

BEN: That also reminds me, Jello for Marcello. I’m not sure if you have and to all of our listeners, I recently saw a truly delightful film called Marcel the Shell With Shoes On, which, if you have not seen, is tremendous and quirky and fun. This is just a completely apropos to nothing… apropos, apra… Apropos?

HEDVIG: Apropos.

BEN: Apropos to nothing at all other than the fact that Jello for Marcello’s name reminded me of this. If you get a chance to, go and see Marcel the Shell With Shoes On. You will not regret it.

HEDVIG: Is it safe for children? Because it sounds like it is.

BEN: I took my eight-year-old son. He liked it. I do not think other children would necessarily. It’s quite weird. It is a documentary about a tiny seashell that is sentient who lives in a house by himself. That is the movie.

DANIEL: Okay, cool.

HEDVIG: I like it.

DANIEL: Cool. That’s a Mailbag. Remember, if you have any questions for us, just get them to us all the regular ways, and we will feature them on an upcoming Mailbag. Now for some comments. From Marty, GRAUPEL. Remember graupel?

BEN: I don’t remember graupel.

HEDVIG: Snow.

DANIEL: Oh, it’s that snow stuff that’s kinda crunchy and slushy and icy and cold. Marty says, “The kind of snow you talked about in Words of the Week episode 73, which you called graupel sounds very much like what skiers in the US refer to as corn snow.”

BEN: Ohhhhh, I understand what graupel is now!

DANIEL: You’ve heard that term?

HEDVIG: Yeah. Well, I grew up, like, skiing and snowboarding in Colorado. So, I know exactly what… It’s like that hard, nasty, kind of big, icy stuff.

DANIEL: Yes, that’s graupel and it’s corn snow. What other…

BEN: Okay. Cool. I got you. And then, when you get to a patch of it and you’re on an edge, it’s like [CRUNCHY ONOMATOPOEIA SOUNDS], [DANIEL LAUGHS] and then you get out of it and you’re like, “All right, cool. I’m skiing and this is great.”

HEDVIG: And it’s only the top.

BEN: Often. Yeah.

HEDVIG: Oh, now I know!

BEN: Like, underneath there’s, like, good snow. Yeah. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Okay. Okay. What other great snow terms have you run across, Ben? Do you have any favorites? I mean, obviously, powder.

BEN: I think powder, but I deeply love that California surf dude linguistic traditions have gone up the mountain. So, powder isn’t powder. It’s ~pow, bro~.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] It’s pow?

HEDVIG: Oh, smashing the pow, man.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

BEN: That’s probably my favourite.

DANIEL: Wow. Skiers, they have so many words for snow. So amazing.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Okay. This one’s from aengryballs. “Hi, I’m listening to your bit on the number of holes in a straw.”

BEN: TWO!!! Sorry.

DANIEL: You know, I actually found your logic, Ben, quite persuasive, because you pinch the bottom of it. How many holes have you got now, dumbass?

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: I subtracted one. Now, what do you got?

BEN: I can’t even remember making that argument, but it’s a really good one! I’m glad I made it.

DANIEL: “I’m listening to your bit on the number of holes in a straw, and I think it would have been interesting to mention the field of topology in maths.”

BEN: What is topology in maths?

HEDVIG: Topology is objects and their relationship.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: Surfaces.

HEDVIG: For example, how much you can simplify an object. So, humans are tubes.

BEN: Okay. I getcha.

DANIEL: As we said.

HEDVIG: Right. That’s the feature… Topology might be interested in how to tie a knot.

BEN: Okay, got you.

DANIEL: Aengryballs continues, — [WHISPERS] I just like this — “I don’t particularly believe popular definitions need to align with scientific definitions, but in this case, I think math’s consensus on the topic is compelling.” Vsauce has a brilliant video on the topic and there will be a link on our website, but I will just summarise. A straw has two openings, but topologically it’s one hole, just like a donut has one hole. You wouldn’t say a donut has two holes. And a straw is basically just a long donut. It’s isomorphic to a donut there.

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: And to a human.

BEN: I will accept that in a topological sense, insofar as humans are tubes, I can concede that a straw is one hole. Which is to say, I guess if you squint real hard.

DANIEL: And garlic is a grass, right?

BEN: Yeah. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: I think the difference is that, I think for Ben, the longer the distances between the two openings, the more they are like two holes.

BEN: Correct.

DANIEL: Right? So, you would say like a donut has one hole and a straw has two.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: Also, because you can bend the straw and then you can’t see through it. And therefore, Ben’s little stupid brain…

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: …is like, “Oh, it’s two holes”

DANIEL: Naïve brain.

BEN: No, that little snippet, that has to come back.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

BEN: Ben’s little stupid brain. We need to isolate that sound, that needs to make an appearance all the time.

DANIEL: But of course…

BEN: There needs to be a button, like in a bad breakfast radio show. Every time I say something fucking dumb, it’s like, “Ben’s little stupid brain.”

DANIEL: But of course, we recognise that the way people perceive an object like a hole or a straw can differ from the way that a topologist might and that’s okay too. Franco via email, “Hi, there. When I finally got to listen to your Speechie episode with PharaohKatt, I was thrilled to hear you discuss this sentence” — which Franco gave us — “She gave her dog biscuits.” And how many sentences can you read that as? How many meanings can that have? We said that there were three on the show. She gave her own dog some biscuits. She gave her, that girl’s dog some biscuits. She gave her, some girl, dog biscuits.

BEN: Dog biscuits. Yes.

DANIEL: Franco says, “I’m sorry to tell you, however, that your analysis fell short of what my American 13-year-old students came with, and they didn’t even know that the word BISCUITS has different cultural meanings.” So, let’s not even go there.

BEN: Oh, yeah, true.

DANIEL: Let me see if I can explain what they came up with. That girl gave her own dog a treat, dog biscuits. That was our number one sentence. That girl gave another girl’s dog a treat, dog biscuits. That was our number two. That girl gave another girl treats for her dog. That was our number three sentence. But then, here are the two that we didn’t think of. That girl gave… gave away her dog biscuits. She gave them.

HEDVIG: No, you need to have AWAY there…

DANIEL: She gave her dog biscuits. What happened to her biscuits? She gave them.

HEDVIG: Away!

DANIEL: I know we’re missing an argument, but you can still say, “She gave her dog biscuits.”

HEDVIG: If you have a sentence beforehand that explains… You need to have a sentence beforehand, or the word AWAY.

BEN: Yeah, that’s fair. That’s fair.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Can I do it with intonation? I’m going to try to do it…

BEN: I’m also a teacher of teenagers, so I am super willing to give them a gimme on this one because I think it’s quite inventive.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah. For sure. Oh, no. These are smart kids.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: 13, you said? Fucking hell.

BEN: And what’s number five?

DANIEL: The five one was that the SHE and the HER are not the same person. So, she gave her dog biscuits. [WHISPERS] AWAY!

BEN: [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: This is Franco again. “Daniel said three to five. So, I guess he nailed it. I suppose if you consider the culturally different meanings of biscuits, it could be 10.”

BEN: Yeah, that’s true. That’s 100% true. You could easily get another four or five just out of biscuits being scones or cookies.

DANIEL: Yep. Yep yep yep. Well, thanks, Franco, for a fun puzzle. It’s been fun to see you on Discord. It’s been fun to see aengryballs as well and everybody. Thanks to everyone who gave us questions for this episode. Thanks to Dustin of Sandman Stories, who still recommends us to everyone. Thanks to the team at SpeechDocs, who transcribes all the words. And most of all, our patrons who give us so much support and make it possible to keep the show going. We love you all. Mwah.

[ENDING THEME]

BEN: If you like the show, here’s what you can do. You can send us all of your ideas and feedback, especially for an episode like this, the Mailbag episode which, low key, tends to end up being, like, our favorite episodes and I think a lot of other people’s favorite episodes as well. And it’s entirely built off cool, interesting listener suggestions, like entirely. It’s really great. Do more labour for us. We love it. You can do that labour for us by following us. We are @becauselangpod in all of the social places. You can also leave us a message on SpeakPipe, like you can talk a message at us. You can find that link on our website. You can send us an email if you are, I don’t know, the crypt keeper, hello@becauselanguage.com. And you can also just do that really cool community-minded thing of just telling someone to listen to us. I do it all the time. When… as in, I don’t recommend my own podcast all the time, because that would be bizarrely conceited of me.

DANIEL: That’s my job.

BEN: But when people are like, “Hey, Ben, what cool podcasts are there to listen to?”, I just rattle off a bunch of the cool, interesting ones I’ve been listening to. Maybe you can do that for us, to your mates.

DANIEL: Another thing you can do is become a patron. You’ll get bonus episodes. You’ll hang out with us on Discord. Obviously, you know this because you already are patrons, but if you’re not, then please come and join up. You’ll also be making it possible for us to transcribe our episodes. The good people at SpeechDocs are doing that for us so that you can read and search our shows.

BEN: Today’s word for SpeechDocs is Rama Lama Ding Dong!

DANIEL: A big shoutout to our top patrons, Iztin, Termy, Elías, Matt, Whitney, Helen, Jack, PharaohKatt, LordMortis, gramaryen, Larry, Kristofer, Andy, James, Nigel, Meredith, Kate, Nasrin, Joanna, Ayesha, Steele, Margareth, Manú, Rodger, Rhian, Colleen, Ignacio, Sonic Snejhog, Kevin, Jeff. Three breaths. Andy from Logophilius, Stan, Kathy, Rach, Cheyenne, Felicity, Amir, Canny Archer, O Tim, Alyssa, Chris, Laurie. Sorry we missed you last episode, Laurie. You’re in this. New this time, aengryballs. And our newest patrons at the listener level, Jo and Franco. Thanks to all of our great patrons.

HEDVIG: Our theme music has been written and performed by Drew Krapljanov, who’s a member of Ryan Beano and of Didion’s Bible. Thanks for listening. We’ll catch you next time. Because Language.

BEN: This is the bit where you once again just put a little loop. Maybe you can do some cool sound effects of like, “Ben’s stupid little brain.”

DANIEL: [BEATBOXES]

BEN: [IN A SINGING TONE] Ben’s stupid little brain. Ben’s stupid little brain.

HEDVIG: I’m so happy that this is your reaction. It makes my life so much easier knowing that this is how you respond to insults.

BEN: [LAUGHS] Oh.

HEDVIG: That’s great.

BEN: How have we gotten to this part of our relationship where you have not realised that my defense mechanism is this?

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Yeah yeah yeah. No, that is true.

BEN: This is how I cope with difficult things!

HEDVIG: And it is also something you share with most of your cultural brethren of the continent you live on.

DANIEL: But also, because we know that Ben is actually brilliant, and even though he’s not a linguist…

BEN: Ah, no. Don’t undercut it.

DANIEL: …he comes with all of the things.

BEN: No, no. No.

DANIEL: My respect for Ben’s tiny brain is immense.

BEN: Don’t neutralise my defense mechanism. It’s when you pat an echidna head to bum. It’s like, “No, these spikes are supposed to be stabbing you.”

DANIEL: No, but you see, this is how… because I cracked your code, I know your real Achilles heel. Is praise.

[BOOP]

BEN: [LAUGHS] Yeah. I don’t know, I have existential angst around, like shame and guilt and stuff like that, but personal safety, zero concern.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Oh, okay.

BEN: Absolute none.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: I was definitely the person where people were like, “Hey, look, a massive up-high thing over water. We should jump off that.” And my brain was immediately like, “Well, that is an excellent idea. Let’s immediately do that.”

DANIEL: Yeah. [LAUGHS] It comes with certain advantages. You get great stories.

BEN: Yep! If you survive, yeah. It’s like one of those things of, like, my entire psychology and perspective on life is essentially survivorship bias, just writ large.

DANIEL: Yes. Well, if you survive, then you get great stories. If you don’t survive, then everybody else gets a great story.

BEN: Yeah, I suppose that’s true. Yeah, oh, don’t we love those delightful dinner party sojourns where a person’s like, “Who wants to hear the time my friend died in front of me? [LAUGHTER] It’s such a gas.”

DANIEL: “You do have the most excellent vignettes.”

BEN: “Oh, Ben, your gruesome tableaus of death, dismemberment, and destruction surely are the very best.”

DANIEL: “Most amusing, Ben.”

HEDVIG: Just going to get a cardigan. I’ll be right back.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Okay. That’s the bit you snip out. It’s just all of that and then Hedvig just very, very unsubtly being like, “Fuck you guys.”

DANIEL: But you know what I’ll do? I’ll cut in about three seconds of silence before that.

BEN: I think she left a good amount. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL and BEN: She knew what she was doing.

[BOOP]

HEDVIG: It’s just funny, sometimes… for example, I do code, you refer to like, “Oh, I’m going to rename the files manually instead of doing it via script.” But you’re not doing it with your hands. You’re doing it with your keyboard.

BEN: Well, that’s the same, isn’t it?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: But you’re using your hands on your keyboard.

BEN: Okay. So, for instance, in a manual car — right? — you use your hands in a way that you would not in an automatic. Is that not a similar principle?

DANIEL: It’s true.

HEDVIG: Yeah. It’s just like less aided by something else.

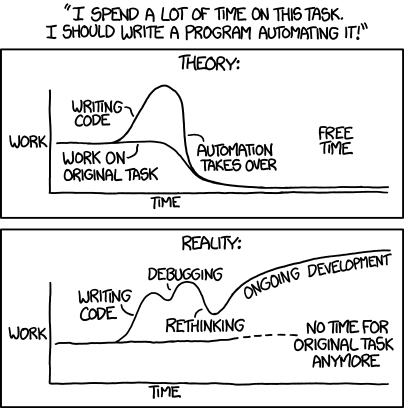

BEN: Yeah. What I also really love is, it also just completely glosses over, certainly in my experience, the amount of time you take writing the script to do the thing nearly always equates to, or eclipses, the amount of time you save by automating. [LAUGHS]