We all have freedom of expression, but what are its limits — social and legal? And how have governments tried to curtail it? We’re talking through the implications of free speech with Dennis Baron. He’s the author of You Can’t Always Say What You Want: The Paradox of Free Speech.

Listen to this episode

Patreon supporters

Huge thanks to all our great patrons! Your support means a lot to us. Special thanks to:

- Iztin

- Termy

- Elías

- Matt

- Whitney

- Helen

- Jack

- PharaohKatt

- LordMortis

- gramaryen

- Larry

- Kristofer

- Andy B

- James

- Nigel

- Meredith

- Kate

- Nasrin

- Joanna

- Ayesha

- Moe

- Steele

- Margareth

- Manú

- Rodger

- Rhian

- Colleen

- Ignacio

- Sonic Snejhog

- Kevin

- Jeff

- Andy from Logophilius

- Stan

- Kathy

- Rach

- Felicity

- Amir

- Canny Archer

- O Tim

- Alyssa

- Chris

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

A 2,100-year-old bronze hand found in Navarra uses words in the Basque languages

https://www.tellerreport.com/news/2022-11-14-a-2-100-year-old-bronze-hand-found-in-navarra-uses-words-in-the-basque-language.SkgVrbh1Ls.html

Researchers claim to have found earliest document written in Basque 2,100 years ago

https://english.elpais.com/culture/2022-11-14/researchers-claim-to-have-found-earliest-document-written-in-basque-2100-years-ago.html

Hand of Irulegi: ancient bronze artefact could help trace origins of Basque language

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/15/hand-of-irulegi-ancient-spanish-artefact-rewrites-history-of-basque-language

Old Italic alphabets | Omniglot

https://omniglot.com/writing/olditalic.htm

[PDF] Lyle Campbell: Language Isolates and Their History, or, What’s Weird, Anyway?

http://www2.hawaii.edu/~lylecamp/CAMPBELL%20BLS%20isolates.pdf

Hedvig’s blog post!

The “Other Languages” in Ethnologue & Glottolog- isolates, contact languages, sign languages etc

http://humans-who-read-grammars.blogspot.com/2015/11/the-other-languages-in-ethnologue.html

Fant 2000 år gammel runestein i Hole : – Dette er en verdensnyhet

https://www.nrk.no/kultur/fant-2000-ar-gammel-runestein-i-hole-1.16256351

https://mobile.twitter.com/RichardDawkins/status/1608122253153107968

How Did Richard Dawkins Undermine Transgender People?

https://aninjusticemag.com/bad-faith-tweets-about-gender-identity-and-race-b38dcfe1a2e7

https://mobile.twitter.com/TabitaSurge/status/1609112931614199810

David Crystal: On the 800-word myth

http://david-crystal.blogspot.com/2010/01/on-800-word-myth.html

1000 Most Common Words In English

https://gonaturalenglish.com/1000-most-common-words-in-the-english-language/

(There are better lists, but this one isn’t terrible for illustrative purposes.)

Pronoun fines and jail time for librarians: Republicans target LGBTQ+ rights with new laws

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/23/republicans-target-lgbtq-rights-new-laws

Florida rejects 54 math books, claiming critical race theory appeared in some

https://www.npr.org/2022/04/18/1093277449/florida-mathematics-textbooks

DeSantis accused textbooks of ‘indoctrination.’ Here’s what he meant.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/05/09/florida-banned-textbooks-math-desantis/

Dennis Baron – You Can’t Always Say What You Want: The Paradox of Free Speech

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/you-cant-always-say-what-you-want/3E5EB1542D914FD2ADF86130B75B884D

Dennis Baron: Does the First Amendment mean “You can’t make me say your pronouns”?

https://blogs.illinois.edu/view/25/1559663297

Challenging “Compelled Speech” Objections: Respectful Forms of Address in Canadian Courts

https://www.slaw.ca/2021/12/14/challenging-compelled-speech-objections-respectful-forms-of-address-in-canadian-courts/

Respecting pronouns is a professional responsibility

https://www.nationalmagazine.ca/en-ca/articles/law/opinion/2021/respecting-pronouns-is-a-professional-responsibili

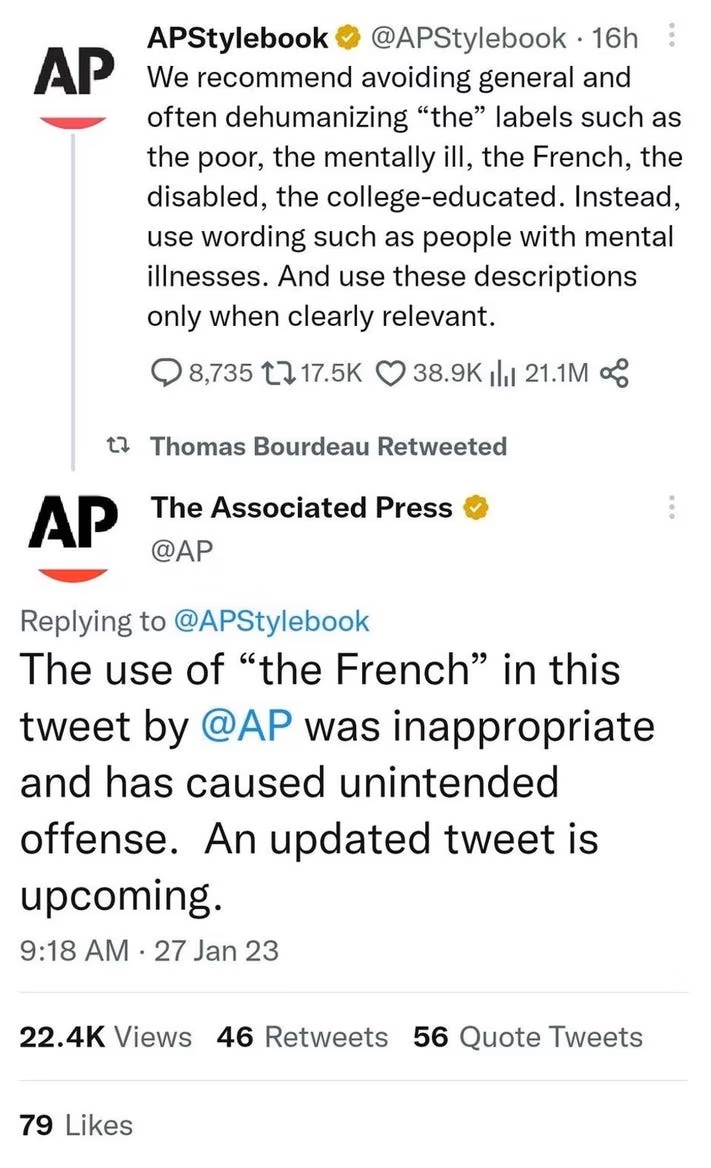

Don’t say ‘the French’ as it’s offensive, AP says

https://www.politico.eu/article/using-labels-the-french-offensive-ap-associated-press-stylebook/amp/

The French Want to Remain the French

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/27/world/europe/ap-stylebook-the-french.html

The philosophy of slowmaxxing

https://thegauntlet.ca/2022/08/25/the-philosophy-of-slowmaxxing/

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

Daniel: Did I lose you guys? Are you still there?

Hedvig: I’m still here.

Daniel: Sorry.

Ben: How about you?

Daniel: I can’t hear you both anymore. Hang on.

Hedvig: I’m making thumbs up on Zoom to signal to him that I can hear him. I can hear him. Can you hear me?

Ben: I can hear you.

Daniel: Yeah, I’m not hearing anything. Super weird.

Hedvig: [in a singing tone] Can you hear me? I can hear you. This is the song of the millennial.

[laughter]

Ben: Oh, my back hurts. I slept funny on my neck.

[Because Language theme playing]

Daniel: Hello, and welcome to Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. I’m Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. He says what he means, and he says it mean. It’s Ben Ainslie.

Ben: I like it. I endorse this introduction.

Daniel: Thank you.

Ben: At least as far as the feedback from some fans goes.

Daniel: She says what she means and sometimes she doesn’t say the thing because you can never get in trouble for not saying the thing. But sometimes, she beats herself up afterwards for wishing she… Oh, sorry. No, that’s me. [laughs]

Hedvig: No, no, no. That is also me.

Daniel: [laughs] Should I keep going? I can keep going. I feel like we’re on the same vibe on this one.

Hedvig: Yeah.

Daniel: It’s Hedvig Skirgård.

Hedvig: Sometimes, colleagues of mine are like, “Oh, I also wish I could do a podcast. I’ll do that later on in my career when I feel more secure and where I don’t feel worried about what people would think about what I say.” I’m like, “Oh.”

Daniel: Should I be worried about that? [crosstalk]

Hedvig: No, I have that.

Ben: “Was that the hack I was supposed to use? Whoops.” Joke’s on your colleague. There is no security coming down the pipe for any academics anymore.

Hedvig: Yeah.

Daniel: No, it’s just one of those things that you just do well. The reason I’m talking about saying what you mean is because later on in this episode, we’re going to be having a chat with Dr Dennis Baron. He’s written a new book, You Can’t Always Say What You Want: The Paradox of Free Speech.

Ben: Ooh, that is interesting.

Daniel: It’s the free speech episode. We’ve been avoiding it. We were sort of dancing around it for a while.

Ben: Yeah. I’m really interested to hear what this guy has to say.

Daniel: Since Dennis and I spoke, I noticed that Staurban Plancker was on Twitter — not because I can see him, because he’s blocked me — but he was just beside himself because somebody’s book got rejected from publication, denying a writer their constitutional right to have a book published, which is just censorship, apparently.

Ben: Or just capitalism.

Daniel: Oh, yeah.

[laughter]

Ben: Just like, “Your thing sucks. Sorry.”

Daniel: The free market has spoken. Anyway, a lot of people say that they’re free speech absolutists, and by that they mean that, they think everybody should be able to say anything.

Ben: Good news.

Daniel: What?

Ben: They’re right.

Hedvig: That you can.

Daniel: They are?

Hedvig: Essentially.

Ben: Yeah, absolutely. They are describing the reality that we currently exist in. Completely.

Daniel: Sorry, I forgot an important bit. Without consequences.

Hedvig: On Twitter.

Ben: Okay, cool.

Daniel: Without anybody saying anything mean about you or…

Ben: I want to be able to say the most awful, hateful, vitriolic nonsense in the world, but no one can say it back.

Daniel: [laughs] In my chat with Dennis Baron, we see that this has never been the case in the history of the world. There have always been consequences for speaking, limitations on expression, sometimes for good reasons, sometimes bad. And we talk about them all. So, stay tuned for that.

Hedvig: Very cool.

Ben: Neato. Before we dig into that good stuff, shall we find out what’s going on in the world of linguistics in the week gone past?

Daniel: Well, I do have a plug. Should I do the plug first?

Ben: I suppose.

Daniel: Okay. Our latest bonus episode was a mailbag in which we laid down the data, Ben’s data about ee-ither, ei-ther, nee-ither, nei-ther.

Ben: [laughs]

Hedvig: My favorite thing we’ve ever done.

Ben: That was actually incredibly… That is definitely the hardest I have ever laughed in one of our episodes.

Daniel: It was.

Ben: The corpus of my ee-ithers, ei-thers, nee-ithers, nei-thers is just rapid fire.

Daniel: Well, it’s all out there on our website for Episode 69. Even if you can’t listen because it’s a patron episode, you can still download… Anybody can download the data and find out why does he say either or neither. We also found in that episode that there’s a bias toward the first half of the alphabet in lists of names and cities and things like that. We speculated on why that might be.

Ben: Giving rise to another bonus piece of content.

Daniel: Do you mean the bit about Hedvig talking to Steve about how Benford’s law could be a thing?

Ben: Hedvig in that episode for those who did not listen to the last episode or could not listen to the last episode, I’m going to say a little bit hung up one of the aspects of the math in one of our discussions, which is totally fine and normal. Like, I get hung up on different aspects of all sorts of things in our discussions.

Daniel: Incredulous.

Ben: But then, we basically threw down the gauntlet for her to engage her very math familiar husband at a PhD level on this topic. For a laugh, we were like, “Oh, by the way, you should record it.” And then, she was like, “Bet.” And did it [crosstalk] listen to it.

Hedvig: Yeah. Also, it was like passing a bug because I told Steve, “Do you know about Benford’s law?” He’s like, “I vaguely heard about it.” And then, he spent a long time researching it. And then he wrote a little Python script and generated data and made plots for us.

Ben: [laughs]

Daniel: Cool.

Hedvig: And then, he made like a whole plan. I was like, “Oh, I think this is going to be a short chat.” We talked for over 50 minutes and multiple times. I had to be like, “Babe, I think we need…” but we were both really interested, and I had to put on my Ben hat to be audience length dumb.

Ben: Dumb? Yeah, you just had to be dumb. That’s all. That’s my hat. It’s a dumb hat.

Hedvig: Because the truth is, in our household, when we don’t record math for podcast, we frequently talk about math for just hours.

Daniel: And you hadn’t ever mentioned Benford’s law? That’s so fascinating.

Hedvig: No.

Daniel: It was that poser Zipf. He was taking up all the oxygen in the room.

Ben: Yeah, bloody Zipf, get out of here. Wannabe dilettante.

Daniel: All right, here’s the thing. If you become a patron, here’s what you get. You get bonus episodes. You get our yearly mail out, which is winging its way to your mailboxussy.

Hedvig: Oh, god.

Daniel: You get extra bits like the Benford’s law bit with Hedvig and Steve. And then you get live shows. And then, I forgot, you get access to our Discord server, which is full of great people having fun.

Ben: It’s neat.

Hedvig: Thank you.

Ben: It’s a really good place to hang out. If you, like me, are of an age or older where you can remember sitting around in IRC channels or on Usenet boards or just random forums for niche interests, it’s basically that. It’s pretty great.

Daniel: Hmm. Well, if you’re a patron, we give you so much. We give you all we got. Become a patron and get all those things, patreon.com/becauselangpod. All right, I’m ready.

Hedvig: [crosstalk] -view.

Ben: Hey, Daniel.

Daniel: Yup?

Ben: What the bloody hell has been going on in the world of linguistics in the last couple of weeks?

Daniel: This story was suggested to us by Ignacio. A piece of bronze in the shape of a hand was discovered about a year ago in Northern Spain, and there’s been a bit of deciphering going on. We think we know one thing that it says.

Hedvig: Wait.

Daniel: That’s pretty cool.

Hedvig: The hand says things.

Ben: [laughs]

Daniel: The hand speaks the truth. It’s an oracle and it can tell the future. So, that’s really…[crosstalk]

Ben: Sign language, obviously.

Daniel: But it only does it in Basque. Oh.

Ben: Okay. My question is, so the bronze hand has some script on it, I’m assuming. This is the thing that we’re actually reading. And the script is in Basque.

Daniel: It may be the oldest example of Proto-Basque.

Ben: Okay. That was going to be my follow up question, because if it’s like, “Oh, the script was Basque and we can read a word.” I’m like, “I’m pretty sure people know more than one word of Basque out there.” [chuckles] There’s a whole population of people who know thousands of words.

Daniel: Why couldn’t they read the other four words? I’m going to get into that, but let’s first of all set the stage. There was once a Basque settlement located on Mount Irulegi, and it had been there for centuries. But around 70 or 80 BCE, there was a war for control of the area, because that was an important area for whoever wanted to control Rome. They unfortunately backed the wrong horse in this conflict, and the winners burnt the settlement to the ground. But what that did was it preserved bits of the houses and artifacts, because all that stuff was stuck under a big old layer of adobe and charcoal.

Last year, researchers found this bronze hand. It’s called the Hand of Irulegi and it has characters in a kind of Iberian script. It looks a lot like Latin, but it’s earlier than Latin and it has some unfamiliar characters in it.

Hedvig: So, it’s 2100 years old?

Daniel: About 2000 years… 2100 years old. Yes, that’s about right.

Hedvig: Okay.

Daniel: We used to think that Basque, the Basque language, Euskara, was not a written language. We thought that maybe the Romans had given them the alphabet and then they started writing from there because all we had was a few coins. We didn’t have anything good. Now we can see that they did use writing. They used a kind of script that is pre-Latin.

Ben: It’s pretty recognizable though. I’m looking at this picture in our show notes and I can see an S and an N and an H and a T. I don’t know if they mean those things necessarily, but the letters are very recognizable.

Daniel: Let me just get there. Yes, you’re right. You know what? You look at the N and that looks kind of like a jaggy N. What else? S looks like an S. E looks like an upside down backwards F.

Hedvig: H, T, D, N, X. I see a lot of things.

Ben: There are some funny ones though. There’s like a weird lollipop symbol and a butterfly looking thing and a few other weird ones. But yeah, I’m seeing more similarity here than when I see Cyrillic script, for example.

Daniel: Exactly. That’s because the Iberian scripts were kind of a precursor. In fact, there were some of the earliest alphabetic systems in the world, by which I mean the symbols represent sounds and the sounds represent both consonants and vowels. Now, the word that they can figure out was sorioneku. That was what that’s supposed to say. Which sounds a lot like the modern Basque word, zorioneko, which means good luck or good omen.

Hedvig: It sounds a lot like it. Yeah.

Ben: Cool. [crosstalk]

Daniel: It really does. I’m surprised that it’s changed so little. That’s really, really weird to me.

Hedvig: It happens sometimes.

Daniel: The other words have changed a lot, which is why we’re not able to read them, but we think we have a few ideas. One of them seems to be [unintelligible 00:10:54], which means a negation marker somewhere. The words have dots between them, which is how you know where the spaces are. But the other four words, hmm, not sure.

Ben: Is it a case of… Can I posit a little Ben Ainslie homebrew based on nothing theory? Everyone’s favorite.

Hedvig: Mm-hmm.

Daniel: Why not?

Ben: Is there a word for word ‘fossils’ in a given language that stay fossilized because they get used in a kind of vaguely ceremonial sense? The obvious one I would go to is something like cheers or prost or skol or something where even if the meaning as such doesn’t really necessarily get bogged down that act, that act, that thing just keeps getting done, it keeps getting done.

Hedvig: Yeah, that has to be done in that way.

Ben: So, wishing someone good fortune might just be like the way that you say, “you’re welcome” or something, I don’t know. Because it always gets used that way, it never really changes that much. Is that a thing? Because it seems to me, “of good fortune” or “good luck” or something is a very strong contender for something people say ritualistically to each other.

Daniel: What do you think, Hedvig?

Hedvig: I think that we think that things that people say a lot tend to get phonologically worn down. But I was thinking that there’s maybe something for Ben there if something is ritualistically very important, maybe not something you say a lot but something you say in church or something.

Ben: Yeah, like at a wedding or a funeral or something like that.

Hedvig: Yeah. If the words are excessively important, then maybe people slow down. I don’t know.

Daniel: We’ve talked about ultra conservative words, words that are for example, on the Swadesh list, there is a list of maybe 200 or 100 words that are thought to not change very much even though they do. Things like blood and “woman and man and children and family words and things like that. I’m not sure if that’s really nothing on the Swadesh list is really ceremonial.

Hedvig: No, but the Swedish list is more like things that are unlikely to be borrowed.

Daniel: Ah, yes.

Hedvig: Which is not really the same as the ultraconservative.

Ben: Could they have just got it wrong? Is this just a case of a word now accidentally sounds and looks a lot like a word from back then and they’re not actually connected?

Hedvig: But 2000 years ago is not ages ago.

Daniel: Yeah, and it’s a very long word. I mean the other thing that ties it in is that it’s normal for this hand to have good luck written on it because it was probably nailed up to the top of a doorway with the fingers down as a way of wishing success upon the house. That would be a totally normal thing for this hand to have on them.

Ben: True.

Hedvig: No, it very probably means that thing. But about the script, I was going to ask. Daniel keeps saying pre-Latin but 2100 years ago Latin did exist and the precursor to what we called the Latin alphabet also existed, probably even for Latin. And this is Mediterranean. Don’t we think that like Phoenicians blah, blah… It’s a whole Mediterranean thing. They’re all inventing this alphabet. It’s little bit maybe unclear who did it first and how it spread, but they could very well be related to Latin.

Daniel: That’s right. So, let’s delve a bit into that. The way it’s usually represented and the way that I’ve taught it is you’ve got the Phoenician alphabet then Greek comes from that, then old italic, like the kind of script that we see on the hand, and then Latin. And the Italic scripts are kind of represented as the precursor to Latin script. But Hedvig is right. They were all kicking around at kind of the same time. What’s important here is that formerly we thought that the Basque borrowed their script from Latin. This shows that they probably didn’t touch the Latin characters at all, they were probably using an old Italic script.

Hedvig: Fair enough.

Ben: Like one of the sources that Latin got it from. [chuckles]

Hedvig: Yeah.

Daniel: Kind of.

Hedvig: And Mediterranean is just like a big lake hay.

Ben: I don’t know. [chuckles]

Daniel: It’s kind of big.

Ben: [crosstalk] -trying to cross it. Probably don’t see it that way, yes.

Daniel: It’s pretty big. It’s thought that this hand, if we can do more work on it, figure out what the other characters are, it may help us to trace the origins of the Basque language.

Ben: That’s really cool. Can I finish off with one funky little Basque-related question?

Daniel: Okay.

Ben: Again, non-linguist Ben asking dummy question. Basque, I know, is a language isolate, which means it has got no familial relationship to any other languages. Not unlike… what are some other ones? Like the Ainu language of the [crosstalk] of Japan.

Daniel: Japanese.

Ben: Japanese, really?

Daniel: Japanese, Korean.

Hedvig: Let’s take some easy… Burushaski, there are other ones. Yeah. There’s about 100 to 200 of them. I made a blog post once trying to count them.

Daniel: I can tell you right now that I’m not going to be telling Hedvig which ones are the language isolates. I totally defer to you, Hedvig.

Hedvig: It’s just that Japanese, Korean people argue so much.

Ben: Hold on, we didn’t even get to my question yet. My question is, isolates exist in the world. They’re super neat and cool as a concept. This is language just exists and then doesn’t have anything to do with other languages. Is there any research, any data that suggests that language isolates suffer word change slower?

Daniel: I don’t think they do.

Ben: Like, would this word be unchanged in Basque, at least in some part because Basque is a language isolate?

Hedvig: No. One way to think about isolates that’s important to keep in mind is that you can also think of them as the only surviving member of their family.

Ben: Aah, okay.

Hedvig: There’s no reason to think that there didn’t used to exist Basque’s relatives, maybe all around the Iberian Peninsula and in France in something at one point, and circumstances such as the Roman invasion and whatever wiped out all the other ones.

Daniel: It’s just the Basque one.

Ben: I got to be honest, this is a real mind blow moment for me. [chuckles] For my entire 11-year history on this podcast, I have genuinely thought that language isolates were Marvel monsters that just got created in a lab and just existed by themselves, like no relation to anything else. [laughs]

Hedvig: Well, yeah, we don’t know this, but just out of… if we pick the…

Ben: But realistically when you think about it, of course they would have family members. They’re just not around anymore.

Hedvig: There are also tiny… lot of language families in the world that have very few languages in them. Like maybe two, three, four, five.

Ben: I know Finnish and Hungarian and Estonian are one language group, and there’s no other members and stuff, right?

Hedvig: No, they’re in Uralic and they have a bunch of neighbors in the Russian Federation, like Semitic languages.

Ben: Okay.

Hedvig: This is also where people are like, “Ooh. Are there deeper families that are larger that we can pull these isolates into?” Blah, blah, blah. But if you think about it, humans have had language for like 100,000, 200,000 years, one of them, [chuckles] probably. The population has been pretty low for a long time. But we spread out all over the world and the 7000 languages that exist today, and the, let’s say 200, 400 language families, depending on who I want to pick a fight with today, there’s no reason to think that there weren’t more in the past, that there weren’t more languages that died out and more language families.

Ben: That’s really cool.

Daniel: Cool.

Ben: Sorry, I digressed just then, but we need to move on. Sorry.

Daniel: Let’s move on to another story. This one was suggested by Birek O Fromage, and it is about runes and a new runestone discovered, which pushes back, this is happening a lot lately, the history of runes in Norwegian languages.

Ben: Can I ask a question straight out of the gate?

Daniel: Yes, please.

Ben: Does a rune refer to a particular character from a particular script or is it a word that we give to a bunch of different characters from a bunch of different languages? If so, what makes something a rune as opposed to a letter or like something else?

Hedvig: A rune is usually referring to members of a certain set of alphabets. In the north of Europe, there are different runic alphabets.

Ben: Okay.

Hedvig: They’re related, and they look a bit similar and they’re usually used to… but just like any other alphabet, you can technically write French in runes. There’s no reason. It’s an alphabet, right?

Ben: Gotcha. Yeah.

Hedvig: It’s not a language. That is as far as I know. There are some that are more well known, like the Futhark.

Daniel: And it’s called Futhark because the first characters are F-U-theta, that kind of thing.

Hedvig: Yeah.

Ben: Oh, it’s like a QWERTY keyboard.

Hedvig: Yes, exactly. It’s like saying that the Latin alphabet is called, like, ABCDEF.

Ben: ABC.

Daniel: Well, it is, because it’s alpha and beta.

Ben: Oh, true.

Hedvig: Also, you say like, “Do you know your ABCs?”

Daniel: Yeah, exactly. Do you know your Futhark?

Ben: More runes have been found for one of these languages or several of these languages?

Daniel: This one’s Norwegian, but I’m going to defer to Hedvig on this one.

Hedvig: No, Daniel has read it. I’m reading it in Norwegian right now. It is so funny because it is like reading troll language.

[laughter]

Hedvig: I don’t think they would mind.

Ben: [laughs] [crosstalk] -ruthless to the other Nords. Honestly, you guys are always so mean.

Daniel: They’re always on each other.

Ben: [laughs]

Hedvig: Different languages conserve different words. They have picked a bunch of archaic words that we didn’t pick. So, when I read it, it sounds old fashioned, but it’s just…[crosstalk]

Daniel: Wow, that’s interesting.

Ben: It sounds like Gimli in the minds of more…[crosstalk]

Hedvig: Yeah.

Daniel: Do you think Swedish would sound the same to Norwegians?

Hedvig: Probably. We picked other things that are archaic. Germans think I’m funny sometimes, so it’s all good.

Ben: Hedvig, you read in troll language, and Daniel, you explain.

Daniel: Okay, what I’m doing is I’m reading the tweet storm from Krister Vasshus, who is a PhD candidate at the Norwegian Language Collections. Here are some of the facts. It’s found on top of a grave. It seems that the skeletal remains of the grave are carbon-14 dated to 25 to 120 CE. But that might not be the same time that the stone was put there. The inscription says Idiberug. The “Idi” means deed and the “berug” means descendant. It could be a family name. Somebody carved F-U-thorn on the side. So, that could have been Futhark. So, this could have been practice. This could have been somebody just…

Hedvig: It’s also fun to think that it is FU.

[chuckles]

Ben: A person called Thorn. Exactly what I thought. Fuck you, Thorn. Fuck you.

[chuckles]

Hedvig: I know it’s not. It’s just funny. You said it, Daniel. You said it so plainly, I was like, “Does he hear that he says what he says?”

Daniel: Okay, some of the interesting things, I was looking at a video by rune expert Jackson Crawford, and he points out that one of the characters is that the S has not three jaggies, but four. It’s like a jaggy pattern. It’s got four jaggies instead of the usual three. He thinks that might because this is part of a creative period. Everyone was having fun with language. They were playing around.

Ben: Well, that happened for English, right? I remember if you read books from 200, 300 years ago, man, stuff was fast and loose. They were doing all sorts of crazy nonsense.

Hedvig: I think we need to get back there.

Daniel: Mm. Yes, please. What this means is that this pushes back the… this isn’t the beginning of runic writing, but it might be around the middle of runic writing, but it’s pushing back the middle a bit. Do we know about where it came from? Because it doesn’t look like Latin script. Some people like to argue that it was borrowed from Latin script, but other people say no, it’s not at all. What do you know, Hedvig?

Hedvig: I thought it was influenced by Latin script as well. I mean, honestly, all over Europe, you get these… I’m not saying that it says… for example, the Norse god pantheon, some of it is suspiciously similar to Roman gods. But then everyone has a fertility goddess, so maybe that’s just like you got to have one.

Daniel: That’s like a combination of borrowing and convergent evolution.

Hedvig: Yeah, maybe I see it as borrowing, even though it’s just like, you got to have one, so we all do. I don’t know where the runic alphabet came from. I thought it was some Mediterranean import, yeah.

Daniel: Okay. Well, I’m really excited that we’re still finding out things, that we’re still discovering things, we’re still finding super old writing. It’s not all been done. For two of these discoveries to come out in the same three-week period, it makes me feel really happy.

Ben: It’s really neat. I like to imagine someone in… some archaeologist/linguist in a cave on a remote, windswept island somewhere looking at some stuff on a wall and being like, “Hold on, hold on. That shit doesn’t look like the shit I know about.” And just being really, really excited.

Hedvig: Yeah. It says here that the people who discovered it in Norway, Steinar Solheim, became målløs, which means speechless [crosstalk] when they realized.

Daniel: It must just be such a moment.

Ben: Exactly. So few times in my life, in the just the humdrum, boring normalcy of my life, am I ever rendered speeches or literally yelling for joy or something like that. It must be such an emotionally potent moment. Good for them.

Hedvig: Do you want to hear me try and read the Norwegian and do my best Norwegian?

Daniel: Sure.

Ben: [laughs] Only if you do it quickly.

Hedvig: Okay. [reading in Norwegian] Jeg ble veldig overrasket. Du stopper nesten å puste og blir litt målløs når du forstår hva du står overfor her.

Ben: Now say all of that in Swedish.

Hedvig: Jeg ble veldig overrasket. Du stopper nesten å puste og blir litt målløs når du forstår hva du står overfor her.

Ben: To be honest, the only difference I could pick up is that you were doing a dwarf voice for the first one.

Daniel: [laughs]

Hedvig: No, I was doing Norwegian.

Ben: [laughs]

Hedvig: It was my best Norwegian.

Ben: [unintelligible [00:25:19]

Hedvig: That’s because that’s their language.

Ben: [laughs]

Daniel: And what does it mean in English?

Hedvig: “I was very surprised. One almost stops breathing and becomes specious when you understand what you are standing in front of.”

Ben: Wow, that is nice. That is really, really cool.

Daniel: I love getting close to that.

Hedvig: Yeah.

Daniel: Let’s wrap it up with a recent tweet by Richard Dawkins on Twitter. Here’s the tweet.

Ben: Boo.

Hedvig: Okay.

Daniel: It’s fun to dig into some bad linguistics every once in a while.

Ben: I know he came up with meme as a concept, but still, what a yucky man.

Hedvig: Maybe not all of our listeners know, but Richard Dawkins sometimes says things that are very uncalled for, is maybe the way.

Daniel: Yes, he does.

Ben: Do you know what? Here’s what I’ll say on Richard Dawkins. He kind of set the template for a thousand people after him of a really smart person who had some really interesting things to say about their area of expertise, being given a microphone and then just going drunk with power and saying a bunch of stupid shit time and time and time again. I feel that just has happened heaps more times since then.

Daniel: A few more times. I’m not even sure that he’s that good a biologist. He’s been going hard on this whole, “Oh, gender is just XX and XY, which is really dumb biology anyway.

Ben: That’s not how it plays out at all.

Daniel: Now, it’s time for some dumb linguistics for Richard Dawkins on Twitter. He says, “A lexicographer estimated that the average 19th century peasant used a vocabulary of 250 words, an educated person 5000, and Shakespeare, 27000-ish, though that last number is disputed. Does that figure of 250 make Origin of language seem less mysterious?”

Ben: Okay, so we need to unpack this. Origin of language is like a famous book. Is that right?

Daniel: I think he didn’t have enough room to write the origin of language. Here’s the idea. Language would have been hard to come up with for early humans. I mean, only humans have done it. Other animals haven’t done it, so it must be kind of hard. But if it only takes 250 words and people in the 1800s were walking around with only 250 words, then maybe it’s not so hard for a language to start after all. That brings down the complexity of the task.

Ben: I pity the poor lexicographer that this guy has quoted. Do we believe this figure?

Hedvig: No, we don’t.

Daniel: We don’t.

Ben: Okay, good.

Hedvig: People dug in, and it seems like this number comes from hearsay. It was like a priest or something who said, “I think that the villagers in my town, where I’m a priest, have about this many words.”

Ben: [laughs] If someone was to ask me how many flowers are in the downstairs garden at your apartment building, I just like glanced out and I’m like, “I don’t know, about 30?”

Daniel: [chuckles] I found this tweet from Tabitha McIntosh on Twitter @TabithaSurge. She says, ” I checked the source trail on this buffoonishly stupid statement. It’s from Friedrich Max Müller in 1866 citing Rev A. D’Orsey, who, in 1861, cited ‘some dude.'” And here’s the money quote. “A country Clergyman informed me, that he believed the labourers in his parish had not 300 words in their vocabulary.” A recent article in the Quarterly extended statements to the great mass of our rural population. He’s like, “I reckon my parishioners are so dumb, they don’t know 300 words between them.” Now, Richard Dawkins, hundreds of years later, is citing this.

Ben: It’s an unnamed random… not even clergyman, like middle rank clergyman is the source. [laughs]

Hedvig: Has been sent down to some parish that he’s not enjoying, and it’s maybe already then… you’re using hyperbole being like, “Oh my god, they don’t even know 250 words. Am I right?” I don’t know if he believes this. Also, we’re comparing… and where people are like, “Oh, Shakespeare, whatever.” Shakespeare’s plays… humans, I fully support the idea that you don’t need that many words to get by on a day-to-day basis. If you count the number of unique words that I say to Steve every day when we don’t talk about maths, it’s probably not that high. But if I’m writing like a book, writing like a play, it’s probably different. Argh.

Ben: Yeah.

Hedvig: This whole thing makes me upset.

Daniel: [laughs] It’s okay.

Hedvig: I just think that Dawkins, he’s shielding it in this, “I’m just asking questions. What do you think about this?” Which is at least better than being like meh, but argh, argh.

Ben: I like that there’s a couple of really key dog whistles here as well. There’s a sniff of Western sieve supremacy because he’s name dropped fucking Shakespeare. There’s a sniff of great man theory of history because it’s just like, “Ah, the average person was barely human.” Just dropping a couple of just super out-of-fashion social approaches to basically every part of human existence.

Daniel: Even so, 250. Anybody thinking for a few minutes should realize that 250 is laughably small.

Ben: That’s like a three-year-old, right?

Daniel: Actually, a three-year-old would be much higher than that. I took a look at the top 1000 words. This is one account of the top thousand words in English. If we only take the top 250 words and exclude all the others, here are some of the words that you’d be without. Four, the number four. Head, black, long, little, house, and yes. Which then gives us the question how many words does a person today know and has that changed since 1800?

Hedvig: We have writing now and much larger societies, so we are bound to have…

Ben: Shit got real complex, yeah.

Hedvig: I don’t know if that makes us better.

Ben: No. [crosstalk]

Hedvig: We just have more shit. And also, like, grammar and phenology…

Ben: Instead of rubbing fucking bison into cave walls, I’m just walking around the fucking Ishimura trying not to die from space aliens.

[chuckles]

Hedvig: Yeah, but also, we’re talking number of words. What is a word? What is a phrase?

Daniel: [laughs]

Ben: No, no, no.

Daniel: You’re absolutely right. What is that?

Ben: I am putting a firm full stop after the “what is a word” impulse. [crosstalk]

Daniel: That’s a wonderful… it’s a super good point. We won’t have time for it today.

Hedvig: That’s okay.

Daniel: I’m just putting it out there.

Ben: [laughs] Hedvig’s like, “It’s fine, I’ll wait.”

Daniel: I’m just asking questions. I think that the number of words hasn’t changed that much that a person would know from 1800 to now. We’ve forgotten a bunch of words, but we’ve also gained new words. I don’t think it’s changed that much. The linguist, David Crystal, has estimated that most people would have an active vocabulary of around 50,000 words. Maybe a really well-educated person somewhere around 75,000 to 100,000 active vocabulary. Again, leaving aside the debate over what counts as a word. And the passive vocabulary, the words that you can recognize even though you wouldn’t use them yourself, probably a third. Again, more than that. So, 250, laughably small. Most people know many, many more words, and that’s the name of that tune.

[interview begins]

I’m speaking with Dr. Dennis Baron, Professor at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He’s the author of What’s Your Pronoun?, The English-Only Question, that’s right, I’m pulling out the deep cuts. And most recently, You Can’t Always Say What You Want: The Paradox of Free Speech. Dennis, thanks for coming on the show and talking to me today.

Dennis: It’s great to be here, Dan.

Daniel: The subtitle of the book is The Paradox of Free Speech. What is the paradox you’re referring to exactly?

Dennis: Well, it is basically that we’re free to say anything we want to anybody we want, but there are always limits. There are limits that we apply to ourselves. There are limits that are imposed on us sometimes by the law, sometimes by organizations that we belong to, sometimes by friends and family. So, paradoxes, yeah, we’re free to say what we want, but sometimes, we don’t even realize that we are monitoring what we say and tailoring it to fit the expectations of the people we’re talking to, avoiding certain taboos or breaking them, knowing perhaps that we have to face the consequences for any language transgressions. Like, family might have a no swearing rule for the children, which the parents don’t necessarily observe. And you know how effective that is. Even if they have what they call a swear jar, where you have to put a nickel in or a quarter in every time you say a forbidden word but then kids grow up and they’re still swearing. So, policing language in that sense doesn’t really seem to work very well.

Daniel: Suppose not. I’ve seen people freak out about the idea of self-censorship. “Oh, no. You’re imposing a set of conditions that are making me self-censor.” I just think that’s a good thing. Sometimes, not saying the thing, it’s a good thing.

Dennis: It’s a natural thing that happens, a social phenomenon. Language is both legal and social in terms of the restrictions and freedoms that we exercise, and sometimes we’re not entirely aware of the social limitations. Certainly, most of us never bump up against the legal ramifications either. How often have you been pulled over by an officer of the law and written up for swearing or swearing in public? In many states in the US, it is still illegal. I don’t know what the situation is in Australia, but certainly in the United Kingdom, it’s illegal to swear on the streets in public. There’s even a guidance on the police website in their frequently asked questions about swearing, and it says, “Yeah, swearing is illegal in public,” but you’re not likely to be penalized for it unless you do it in front of a police officer.

Daniel: Well, that’s kind of a problem, because what happens is somebody will have a run-in with the police, and then if they do swear, because maybe they belong to a community that is more sweary, what happens is the people who get called up for this kind of thing are more likely than not to be Aboriginal people.

Dennis: Right. Sure.

Daniel: It hits them harder. We’ve seen a number of cases like that. I haven’t had any legal ramifications for language. I’ve had some social ones. In the book, you pivot away from the social repercussions of language, and you focus on the legal, and that’s natural because freedom of speech, freedom of expression. Is it okay if I say freedom of expression? Because I don’t just want to focus on speech. I want to focus on sign language.

Dennis: Absolutely. Signing, writing, any form of communication. I do try to indicate in the book that when I say speech, it also includes signing, writing. It’s shorthand, but freedom of expression, the right to express yourself and to access information. And what goes along with that is the right not to be forced to say something or to write something or to sign something that you don’t believe in. So, it works two ways. It’s like you’re free to say what you want, and the government is really not supposed to impose restrictions on that. The government is also not supposed to force you to say things that violate some deeply held belief.

Daniel: Mm. Okay.

Dennis: Like the earth is flat, not to end a sentence with a preposition.

Daniel: [chuckles] Got you. Now, freedom of expression is written into the US Constitution, but in other countries, it’s not. In Australia, we like freedom of speech, we think it’s pretty cool, but it’s not one of the things in our constitution. I think the USA has a lot of unique issues when it comes to this topic. Can you make the case for me that this issue is relevant for non-Americans as well?

Dennis: Sure. Even though it may not be inscribed in… Does Australia have a written constitution? I reveal my ignorance here. Or is it an oral tradition like the British Constitution?

Daniel: It does have a constitution.

Dennis: Yeah. I believe Canada does, and I assume perhaps New Zealand.

Daniel: I’ve never read it.

Dennis: Never read it. Okay. It’s like the terms of service that you don’t read, you just click to agree.

Daniel: Scroll to the bottom.

Dennis: Scroll to the bottom. The whole concept of free speech and government interference with speech is pretty universal. And even though the US is an outlier among liberal democracies in terms of having free speech inscribed in its constitution, England and the EU take a more balanced approach to say, “Basically you have free speech but certain kinds of speech, hate speech, discriminatory speech also can be seen as violations of the law and can be penalized by the government, by fines, by…”I suppose, ultimately imprisonment but I’m not sure. There is a more balanced approach to the freedom to communicate and the freedom to be safe from harmful communication. It’s a concern there too. It’s framed differently in terms of the legal system.

But on the ground, in vivo, as you go through life communicating, you face the same kinds of problems. What kind of speech is okay? What kind of speech is frowned on? What kind of speech is going to get you trolled on the internet? What kind of speech is going to have your friends desert you, your parents correct you, your teachers mark you down, your boss fire you for saying something or writing something or communicating something that they disapprove of?

Daniel: When I went to the dear old Brigham Young University, there were professors who were always in trouble because they took a line against the church party line or the university party line. So, there were always debates and discussions and issues surrounding freedom of speech. I always felt a very strong kinship toward them and toward the freedom of speech angle, because the idea that freedom of speech is generally good, that people who try to repress freedom of speech are not on the right side, why is it good? Can we just get down to bedrock? Why is freedom of speech a good thing?

Dennis: [laughs] Why would it be a bad thing? What’s wrong with…? As justice of the Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis said in, I think, it was 1927, “The freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think. Why should there be restrictions on that?” We’re free to say whatever we want. We are not free to avoid the consequences of the speech. That’s where the social and legal systems come into play because you utter something, you write something, and your audience, whoever it is, whether it’s a targeted audience, I’m speaking to you specifically, or it’s a general audience, or it’s a passerby on the street, they are free to criticize you, to accept and congratulate you for saying what you said, to penalize you, to correct you, to laugh at you. And the worst thing of all, for somebody like me, who’s a writer, to ignore you, to ignore what you say. Oh, my god, that’s the worst thing.

Daniel: That’s a wonderful thing, the right to ignore somebody because I say this person is… I’ve met people who say, “You should never ignore anyone because everybody is deserving of your time.” No, they’re not. I have to make choices. There are so many people. Not everyone’s deserving of my attention.

Dennis: Absolutely. Somebody says, “Look out for that cliff.” Okay, maybe they deserve a little more attention, but if you’re in the middle of the desert, maybe you can ignore them.

Daniel: Yeah. Maybe not everyone deserves a spot on the stage of a university.

Dennis: Absolutely. Freedom of expression doesn’t guarantee you a platform to express. That’s something that you have to negotiate. You have to be invited. You have to take your speech turn. Even in a normal conversation, there’s this kind of turn-taking mechanism that applies, and people who violate the turn-taking mechanism are subject to responses from the other people in the conversation. They can ignore them. They can say, “Hey, I’m not done. Don’t interrupt.” Or, they can say, “Okay.” They can just accept your interruption and move on. So, it gets complicated, but yeah.

Daniel: I’ve got a list. Because from my wild and woolly days of everybody say everything free speech boosterism, I now have a more nuanced view, and I do have a list of kinds of speech that I would like to have banned or controlled. Can I just tell you what those are?

Dennis: Yes. So, if you’re the boss of the world, what would you ban?

Daniel: I’m the boss of the world. Hate speech. When I say hate speech, I mean expression that encourages violence against a group of people. The reason why I want to ban that and make that illegal is not just that it might result in violent behavior against them, but also that I think it makes people not want to identify as that group of people that you are vilifying or encouraging violence against. Then, that has a chilling effect on their free speech. I would rather have their free speech than hateful violent communication encouraging violence against a group of people. What do you think? Sound good?

Dennis: Sounds good to me. But let me think like a lawyer for a second.

Daniel: Which you are not.

Dennis: I am not a lawyer. I do not play a lawyer on TV.

Daniel: [chuckles] No.

Dennis: Or on the radio or on podcast.

Daniel: Or on podcast.

Dennis: Okay. How do you define free speech? Look, there’s whole bunches, whole categories of speech in the US, that are not covered by the free speech guarantee of our Constitution. Threats are not protected speech. Obscene speech has always been viewed as outside the protections of the First Amendment in the United States. The question is, how do you define a threat? How do you define obscenity? The legal system has not been very good at establishing guidelines so that you know in advance or even after the fact, whether you’ve crossed the line, whether you have said something that is obscene. One person’s obscenity is another person’s lyric.

Daniel: Precisely.

Dennis: So, how do you define it? How do you know when someone has threatened somebody else? Is it an objective observer, if there is such a thing, who gets to judge you? Is it the person who receives the ostensible threat? Well, what if they are just generally paranoid, and think of everything as a threat? What if the threat maker says in their defense, “Hey, I was just kidding”?

Daniel: Yeah, they’re really credible. That changes the game.

Dennis: “I didn’t mean it literally. I’m just joshing around.”

Daniel: Yeah.

Dennis: Are they gaslighting you? Are they for real? Yeah. Sometimes, people make a joke, and it falls flat. Sometimes, people disguise a threat as a joke, as a means of self-protection so you can’t say I threatened you. “I was just kidding. [chuckles]”

Daniel: What about slurs? Do slurs count as hate speech?

Dennis: They could. You get to define it. You mean like a racial or ethnic or religious slur?

Daniel: Yeah, that kind of thing.

Dennis: That kind of thing. Sure. You can sweep them into the category of hate speech pretty easily, I think, even if it’s a single word. Why not? If you’re attaching a label or calling somebody a name, fighting words are a kind of thing that justify a negative reaction to what you say. The question is when you establish a category like hate speech, and obviously that is the case in UK law, I’m not sure what the situation is in Australia, and I think Canadian law tries to define various kinds of hate speech, they usually narrow it down to speech against someone for, say, sexist or sexual orientation or gender status or gender identification. Those sorts of things that you narrow it down to a category that makes it little bit more easy to define in legal terms, in terms of setting boundaries and letting the public know what kinds of speech is being discouraged. But even there, there are edges where it’s not so clear how hateful this is or what if you’d have a negative term and you use it in an ingroup to flip it to something positive? There’s that kind of issue as well. An outsider can’t say that to me or about me, but I can say it to my fellow members of this particular racial or religious group or ethnic group. That happens all the time.

Daniel: Mm. Okay, so the hate speech category isn’t that simple. We’ve already touched on my second category, which is threats, harassment, doxing.

Dennis: Those are, in terms of American law, and I imagine in terms of legal systems elsewhere as well, the threats are not protected in any way. The question then is establishing what counts as a threat.

Daniel: Got it.

Dennis: In the US criminal law, you have to have intent. You have to have… sometimes it’s called criminal intent, sometimes it’s called mens rea. It’s basically you have to be able to formulate a notion of right and wrong and that you intend something to be harmful rather than benign. You have to also utter something, and not being forced to do it by somebody else, somebody’s not holding a gun to your head physically or metaphorically forcing you to make the threat. You’re not talking in your sleep.

Daniel: Interesting.

Dennis: You understand the meaning of the words. In other words, if you don’t speak a language and somebody hands you a card with words in that language and says, “Read those words,” and those words are threatening in that language, but you don’t know that because you don’t speak the language, that absolves you. You’re not making a threat legally in terms of American law because you don’t know what the meaning of the words actually is.

Daniel: Speech acts are complicated.

Dennis: But I’ll give you an example from the book. The earliest recorded prosecution for threatening a president… Now, threatening or making fun of the president is like a national pastime in the US. I think making fun of the leader is a national pastime anywhere there is a leader. I don’t know, it was 1798, 1799 around then, John Adams was the second president of the United States, passed a sedition law saying it was illegal to criticize the government for anything. This is a clear violation of the First Amendment. People challenged it as a violation, but they were afraid to do so in public because that would be criticizing the government. People were arrested and fined for criticizing the government. Most of them were newspaper publishers that belonged to the opposite political party from Adams.

Daniel: Setting the stage. Wow.

Dennis: Anyway, speaking of setting the stage, John Adams travels from Philadelphia to his home in Massachusetts, passing through New Jersey, and he’s doing it to avoid… I think, it was an outbreak of yellow fever or something in the capital. So, he’s going home to ride out the threat from the disease. His carriage passes through a small town in New Jersey and the residents know he’s coming. In honor of the president, as the carriage passes through town, they fire a 21-gun salute or something or some cannons. They’re firing blanks. They’re just saluting the president.

This guy is standing outside a tavern, and somebody says, “Oh, they’re firing the guns at John Adams to hail this passage.” The guy says, “For all I care, they might as well be firing through his arse.” The tavern keeper is standing next to him because they’re all outside watching the carriage go by. And he says, “That, sir, is sedition.” The guy gets arrested and tried for threatening the life of the president even though Adams had no idea that any of this was going on. He’s just sitting in his carriage trying to get home before disease strikes. The cannons are firing blanks. Even if they fired at the president, nothing would have happened. The guy is just the local drunk, basically just saying something snarky that occurs to him as the authority figure arrives. But he is arrested, tried, convicted, fined, and he sees this as a no-win case. He pays the fine and gets on with his life. But was that a threat?

Daniel: [scoffs] I think not.

Dennis: The prosecutor thought it was. The guy who turned him in thought it was. And he’s turning in a patron. This guy’s going to buy less booze from him if he’s in jail, but this is against his own interest. The prosecutor thought he was, the judge thought he was. The guy finally decided it’s easier to just plead guilty and get on with things. Besides, by that point, Jefferson had become president and the sedition law was allowed to expire.

Daniel: [chuckles] Let’s go to my last category that I would like to not ban, but I would like to control. I think control happens in different ways. Disinformation which is, I think, harmful to the dynamic of gathering information and making informed choices. Like, we have this idea that free speech is good because we exchange ideas and the good ideas float to the top as people believe them. But disinformation from bad actors inverts that equation. Disinformation is an incredibly useful strategy. I mean, lies are incredibly advantageous. They’re easy to make. They’re quick to make. They can get out there. People already believe them. So, I think I would try to control disinformation.

Dennis: Okay, so you want to ban lies. You want to make lying illegal.

Daniel: [laughs] I can’t make lying illegal. I would go to jail. But disinformation is a little different? How would I find define that?

Dennis: It’s different from lying. Okay, so it is more…

Daniel: I don’t think I would like to legally sanction it, but I think I would like there to be good ways for social networks, hint-hint, to control, to do fact checking. And I know-

Dennis: Right. For sure.

Daniel: -a lot of people hate fact checking.

Dennis: Well, a lot of people hate fact checking and when publishers stop fact checking, a lot of stuff slips into edited material that should not be there. It’s [unintelligible 00:56:20], they’re honest mistakes… I’ve made mistakes in my writing. I’m sure if it hadn’t been for fact checker in the editorial process, that would have been embarrassing at best, problematic, sometimes leading to the exact opposite interpretation of what I had intended. So, fact checking is certainly important. How do you fact check? How do you check anything on something like social media where you’re dealing with millions and millions of posts a day internationally in multiple languages? Humans can’t do this.

Daniel: Well, this is why it’s so hard. I mean, nothing scales.

Dennis: Nothing scales. And algorithms aren’t very good at doing this. They cannot detect sarcasm or humor. They can’t differentiate between legitimate criticism and disinformation. All this came to the surface with the start of COVID where all kinds of disinformation starts appearing in a context where it’s hard to get almost any kind of reliable information, and eventually you start seeing the science and medical community weighing in. But even there, there’s a certain amount of disagreement and then people jump on some scientific report that suggests something’s not as effective as it should be, and then they amplify that.

Daniel: And then, it gets picked up by a social community that makes it a part of their identity. And then, you just can’t ever get out.

Dennis: Right. People get crazy. What are you going to do? You want to outlaw that? Outlaw crazy speech?

Daniel: No, I don’t know. I don’t outlaw it. I don’t think we can outlaw it.

Dennis: [laughs]

Daniel: I think maybe we could do better at picking up on it, maybe somehow.

Dennis: Where would we be as commentators about language if everything was so buttoned down and regulated. We’d have to say, “Well, these controls are ridiculous.”

Daniel: Yeah. They might go too far. Okay, we’ll tell you what.

Dennis: You’re destroying the data.

Daniel: I’ll work on that one.

Dennis: [laughs] Look, we all have speech that we hate. We all have speech that we would like to ban if were the boss of the world. I asked my students this every semester. I’d say, “What’s the one thing that you would change about the English language, if you were the boss of the world?” Invariably, there were three things that would come up. Too much swearing.

Daniel: Oh, please.

Dennis: This is from 18- to 21-year-olds.

Daniel: Prudes.

Dennis: Right. Too much swearing. And I say, “Do you swear?” They say, “Yeah, I do, but it’s too much.”

Daniel: [laughs]

Dennis: “I know it’s wrong because I can’t stop myself. So, there should be a law against it.” Okay, so there’s that. They would reform English spelling.

Daniel: Yeah, good luck.

Dennis: They would reform English spelling. English spelling is crazy. They’re playing right into my hands because we got a whole unit on spelling reformers and how ineffective those movements have been since the 13th century. The third thing is that they object to fillers. They object to people who say “you know” all the time.

Daniel: Those things are great, or “like.”

Dennis: Or “like” or “um” or “er” or “stuff like that.” We talk about the importance of fillers in discourse and how they are basically placeholders to tell everybody else, you’re not through talking. “I’m just throwing the sound in here to let you know that I’m not giving up my speech turn, but I’m trying to formulate the next idea,” a little more precisely or something like that.

Daniel: To help you remember things that other people say.

Dennis: Yeah, they’re all natural parts of free speech function, but these are the things that my undergraduate students would invariably seize on, those three things swearing, spelling, and fillers as if they were the boss of English. And then, they have to come up with a way of banning this stuff. I didn’t let them off the hook. “What’s your mechanism going to be? Are you going to do it through the education system? Are you going to do it through the legal system? Are you going to exert social pressure?” It’s a great teaching tool because they would start thinking about what are the forces that control language that are external to the speaker? We like to think that we have free will, and of course we do, but in the context of a social setting where there are all kinds of hidden restrictions that we don’t even realize the laid lines, the categories and so on that we unconsciously guide our locutions.

Daniel: Okay, well, then I won’t try to ban disinformation legally, but I will try to… I think I like education. I know it doesn’t work.

Dennis: Yeah.

Daniel: But I’ll try it.

Dennis: It works a little. There is a role for education. [laughs] Longtime educators who don’t believe in formal education like me, but who realize that it keeps the lights on.

Daniel: Okay, you’re very optimistic, I’ll give you that.

Dennis: [laughs]

Daniel: Now that we’ve gotten through my things that I don’t like, let’s take a look at the people who actually have been in charge. What have they tried to ban or control? We’ve already talked about one, and that’s obscenity. I guess that’s difficult because we don’t really know what obscenity is, but it involves judgment. You know it when you see it. It involves judgment, but everything involves judgment. So, that’s not a problem.

Dennis: Right.

Daniel: I noticed in your book that you have banning different languages entirely other than English. What was up with that?

Dennis: Oh, well, this is nothing new in the world of language regulation, but in terms of US history, certainly the idea of what should be… United States has not declared an official language ever. There have been moves to do so throughout its 200 plus year existence. A majority of states in the US have declared official languages. The state I live in, the state of Illinois, declared in… was it 1923, that American-

Daniel: Not English.

Dennis: -was going to be its official… not English.

Daniel: [laughs]

Dennis: You’ve got to put it in a kind of historical context.

Daniel: Talk American.

Dennis: This is part of the American reaction against World War I. It was a kind of shock to the American system to get involved in that kind of international conflict. In fact, the US didn’t enter the war for the first three years, two and a half years of the war. We didn’t enter until 1917, and by 1919, it was pretty much over. But it was an amazing shock, and the pressure for the US to remain neutral before the war was very strong. Opposition to the war in the US was reasonably strong. The US passed a second sedition act in 1918, banning interference with the war effort, and several hundred people were arrested and fined for doing things like calling President Woodrow Wilson a bad name.

Daniel: Oh, yeah, okay.

Dennis: Some drunken guy in the middle of nowhere Montana, says, “Oh, Wilson is a drunken bum. He’s a stooge of the capitalists. I would go to Washington and blow the whole place up.” He gets thrown in jail for sedition, for encouraging opposition to the war. The only people who heard him were ten other drunks in the tavern, and he was several hundred miles from the nearest army base. So, certainly could not influence the troops to not cooperate into war effort. But they threw him in jail, as if he were an actual spy or somebody who was trying to shut down a munitions plant or blow up a recruiting office or anything like that.

So, in reaction to that harrowing international war experience, after the war, America retreated into its shell to a great extent. They wouldn’t give Wilson permission to join the League of Nations, for example, because that was too international. They’re all quoting George Washington’s admonition to avoid foreign entanglements.

So, as a kind of failed message to the British, a coalition of ethnic politicians, basically Irish and Jewish politicians in Chicago, pushed through this law, making American the official language. The Irish politicians didn’t like the UK policy on Ireland, and the Jewish politicians didn’t like the policy on Palestine. So, this was a message to the Brits. Between 1923-24 and 1969, American was the official language of the state of Illinois. In 1969, the legislature changed it back to English being the official language of the state of Illinois on the grounds that there was no such language as American. For that whole time period, schools still taught English. They didn’t teach American. Everybody spoke English. They didn’t speak American.

Anyway, the concomitant idea was that if you spoke a foreign language, a non-English language, a non-American language, you were somehow unpatriotic. That surfaced during World War I as well. In 1918, the governor of the state of Iowa, a guy named William Harding, banned the use of foreign languages anywhere in the state in public.

Daniel: Wow.

Dennis: By in public, he meant on the street, on public transportation, streams and streetcars, basically, at public meetings, in schools, in churches.

Daniel: What, even Latin?

Dennis: I don’t think there were very many mosques or synagogues, but there were churches in Iowa. And yeah, he was kind of silent on the Latin mass thing because this was before Vatican too. So, the Catholic mass was in Latin in 1918, but it was basically an attack on the German Lutheran and German Catholic churches in the state, which also ran private schools in German. Somebody asked him, “Well, why don’t you just ban German? Why are you banning all languages?” He told them with a straight face, “The Germans are very sneaky. They’ve learned to spy in every language, and so I have to ban all those languages.” And nobody thought to ask him, “That means they can spy in English, right?”

Daniel: [chuckles] So ban English. [laughs]

Dennis: Yeah.

Daniel: History does not record his response.

Dennis: Yeah. Government officials are not required to study logic, I guess.

Daniel: We were talking once a long time ago to Michael Gordin, who wrote Scientific Babel, and he recounts how that action and others like it across the US during that time was enough to knock German out of its spot as a language of science. And it just isn’t.

Dennis: For sure. As a language of science, it also is the language that was before 1917. 25% of American high school students studying a foreign language studied German in their school.

Daniel: And after?

Dennis: And after the war, that plummeted to single digits.

Daniel: Wow.

Dennis: Foreign language in general in the US, foreign language study never recovered from the pro English sentiment that generated around World War I, and there were voluntary bans on German music, on German food. The producers of the National Sauerkraut Association petitioned to have the name of the food changed to Liberty Cabbage.

Daniel: [laughs] Not Freedom Cabbage, surely.

Dennis: Not Freedom Cabbage. The Freedom Fries came later in reaction to-

Daniel: Goodness gracious.

Dennis: -to anti-French feeling around the Gulf War not that long ago. This whole thing, this was going on in Germany, too. There was anti-English and anti-French movements in Germany during World War I. Foreign language signs were banned in Berlin, cafes had to change their names from French names to German names.

Daniel: There was a lot of assimilation going on.

Dennis: National conflict always targets language as a symbolic gesture. You see that with the Russia-Ukraine conflict, where attitudes toward Ukrainian and toward Russian… It’s silly to talk about language when the bombs are going off. But in effect, you change how you refer to Kiev or Kyiv, and does that affect the chicken dish? It chicken kyiv instead of chicken kyiv? It impacts the fate of teachers of those languages in the schools and all sorts of language stuff going on with that. In lots of post-Soviet Europe, you see language issues suddenly coming to the fore. Banning foreign languages in the Czech Republic, for example, or in the Slovak Republic, all kinds of language conflicts. What do you do with the Russian teachers once you establish your own independence? Do they have to retrain as teachers of Lithuanian, or do they have to go back to Moscow, or what do they do? It becomes an issue.

Daniel: Yeah. I noticed also in the book that it wasn’t just different languages that were targeted, but so-called bad English, I noticed this thing from the Better American Speech Committee. Do you mind if I just read some of this?

Dennis: Oh, please, go ahead.

Daniel: “I promised that students had to recite or take…” It said, “I love my country’s language. I promise that I will not dishonor my country’s speech by leaving off the last syllables of words,” mm-hmm. “That I will say a good American yes and no in place of an Indian grunt ‘um-hum’ and ‘nup-um’ or a foreign ‘ya’ yeah or ‘yeh’ and ‘nope.’ Didn’t know those were foreign. How about that? There’s more.

Dennis: It’s part of the Americanization movement that was also flourishing before and during World War I and after it because the US was dealing with waves of European immigration from the mid-19th century on, but huge waves between the 1890s, 1880s, 1890s into the 19-teens. The idea was that schools became one of the focal points for Americanizing the children of immigrants, making sure they spoke English. This Americanization committee, this American Language Committee of the Chicago Woman’s Club at the time started what came to be known as Better American Speech Week. It became a national phenomenon for a few years.

And it was a two-pronged program. One was to get immigrant children to perfect their English. Many of them came with no English. My mother was born on the lower side of Manhattan in 1911. Her first language was Yiddish. She did not learn to speak English till she got to kindergarten. She basically learned it from interacting with other children who spoke English. This was a common immigrant experience. Her parents had immigrated, but she was born in the US but still, her heritage language was her native language until she started school. So, the schools were teaching English to children who were born here to foreign born parents… born in the US to foreign born parents, and they were also trying to improve the English of those who spoke English as their first language. So, what comes into play then are class issues as well as ethnic issues. Trying to get everybody to speak proper English was basically a kind of upper middle class idea of what standard English ought to be.

Daniel: Audience, we are doing lots and lots of air quotes during this section like “improve” and “better English.”

Dennis: Yeah, exactly. One of the things that interested me, I knew my mother when she grew up, became a schoolteacher. I noticed as a child, when my mother would get together with her schoolteacher friends, that they all sounded funny-

Daniel: Really?

Dennis: -to me, and they sounded like my schoolteachers as well, and they didn’t sound like ordinary people. There was a kind of schoolteacher accent among the New York City schoolteachers. Then later on, after I studied language in college and in graduate school and the social pressures applied to immigrants, I realized that New York City was one of the places that established in order to become a teacher, you had to pass a speech test.

Daniel: Oh, really?

Dennis: Not only did you have to have a college degree and a major in certain courses and how to teach courses and things like that, but you have to go before a group of live examiners and speak, do a little oration. If you had any trace of a foreign accent or you had something foreign in your name and that you were identifiably from some immigrant group, Irish or Italian or German or Jewish or whatever, that was a strike against you. In order to pass the test, the candidates had to develop this kind of hypercorrect pronunciation.

Daniel: Yeah. Gross.

Dennis: So, the teachers from my mother’s generation who had to take that speech test to get their teaching license, all spoke with this amazingly precise kind of English which they used in conversation, not just in a teaching moment, but as part of their daily interaction. To me, it sounded weird, but then I understood why that happened. The state of California did that, kind of required a speech test too, in order to keep Asian students out of the teaching corps. It was used to try to eliminate certain kinds of groups from the teaching profession, the idea being that somehow you are going to subvert the kids if you were allowed to be yourself.

Daniel: It’s an old story, isn’t it? It just happens over and over again.

Dennis: We still are trying to control our teachers. We still are basically operating on the assumption that the teacher knows nothing, and the teacher can be told what to do, told which books not to teach and which topics to avoid and all of that kind of stuff that deprofessionalizes what really is an important profession.

Daniel: That brings us right up to the present day where we’re talking about the authoritarian right trying to ban certain books that portray LGBTQ people positively, trying to ban what they call “critical race theory,” which is an academic pursuit, but not something that teachers consciously teach in high schools. It’s just any acknowledgment that racism exists, basically. It involves removing books from libraries. Schools and teachers are under enormous pressure right now.

Dennis: In the name of free speech, they’re banning speech. To protect the free speech of students and parents, ostensibly, they are banning books, they are banning topics for discussion. We are back to teaching that the earth is flat, and the dinosaurs did not exist.

Daniel: This also goes to… I just picked up this Guardian article by Gloria Oladipo. The article is called Pronoun fines, this is your area, and jail time for librarians: Republicans target LGBTQ+ rights with new laws. And I’ll just read a section here. This is North Dakota. “One bill, rejected on Friday, mandated people affiliated with schools or institutions receiving public funding having to pay a $1,500 fine for using gender pronouns other than those assigned at birth for themselves or others.” And that effort failed but this is what they’re trying to do.

Dennis: Absolutely. If you can’t teach about pronouns in school, where are you going to teach about pronouns?

Daniel: Teach grammar. Not pronouns or something.

Dennis: Grammar schools were called grammar schools because they taught grammar. Go figure. Go figure, North Dakota. You know what? I was surprised when I read that story that they actually didn’t pass the bill because those are the kinds of bills that are being passed. What was the opposition? I’m glad it didn’t pass.

Daniel: It’s a good thing.

Dennis: It’s an example of how crazy legislators can get. I mean, they’re reflecting a general attitude. People are buying into this. It’s not like they came out of nowhere. They feel empowered to do this because they feel there’s enough public support for banning pronouns.

Daniel: By which we mean, what, singular “they”?

Dennis: By which we mean…

Daniel: Neopronouns?

Dennis: The pronoun has become a symbol for wokeness rather than a placeholder for a noun.

Daniel: Well, that makes sense though because pronouns stand in for things. So, I guess when you’re demagoguing pronouns, you’re demagoguing people.

Dennis: That’s absolutely true. Of course, that is the history of pronouns. The history of pronouns is one of including and excluding.

Daniel: Right, inclusively and exclusively, but also who we bring into society and who we keep out.

Dennis: Exactly.

Daniel: The book is You Can’t Always Say What You Want: The Paradox of Free Speech by Dennis Baron, Professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. It’s available from Cambridge University Press. Dennis, how can people find out where you are and find out what you’re doing?

Dennis: You can follow me @DrGrammar on Twitter and follow me on Facebook. I haven’t been blogging very much lately, but I do blog at the Web of Language, so you can check that space out too. I will be picking up some themes from the book to blog about over the next few weeks.

Daniel: The Web of Language is really worthwhile. I have assigned bits of that to my students on many occasions. Thanks for hanging out with me and talking about the book. This was really fun.

Dennis: Thank you, Daniel. And it’s always good to talk.

[interview concludes]

Daniel: It’s time for Words of the Week. The Word of the Week this time is “the.”

Ben: What?

Daniel: The. Three little letters. It’s the most common word in English, and it’s been in the news.

Ben: How has “the” been in the news?

Hedvig: Yeah.

Daniel: In times past, we’ve mentioned why you don’t probably want to use “the” with groups of people.

Ben: Yeah, because “the” would sound super racist.

Daniel: Yeah. Well, yes. Like when a right-wing political figure referred to “the” blacks.

Ben: [shivers] Such shivers.

Daniel: Why is that gross? Why does that give you the shivers?

Ben: Well, because it collectivizes and objectivizes a group of people.

Daniel: Right. Okay.