It’s Eurovision season! We love to talk about what we can learn about language from this international song contest, but even we didn’t realise that there was so much to learn. Language choice, language policy, language and gender and metaphor — and all of this has been packed into a unit at Umeå University: Linguistics and the Eurovision Song Contest. Paulette van der Voet and Solveig Bollig are heading up the course, and they’re here to tell us all about it… and nerd out with Hedvig besides.

Timestamps

Cold open: 0:00

Intros: 0:39

News: 7:39

Related or Not: 26:41

Interview with Paulette and Solveig: 38:53

Words of the Week: 1:30:08

Comment from John: 1:49:18

The Reads: 1:53:53

Outtakes: 2:02:25

Listen to this episode

Patreon supporters

Thanks to all our patrons! Here are our patrons at the Supporter level.

This time we alphabetised them based on what their name would autocorrect to, if they could only autocorrect to the names of animals for some reason. Which animal name is closest to yours? We used the standard Wagner-Fischer algorithm for Levenshtein distance.

- Alyssa & Ariaflame: alpaca

- Aldo, Amy, Manu, Andy B: ant

- Canny Archer: anteater

- Nasrin: baboon

- Rodger: badger

- Kathy: bat

- Rene: bee

- Nikoli: bison

- Rachel & James: camel

- Colleen & Whitney: chicken

- O Tim & Elias: clam

- LordMortis: cormorant

- Chris W: crow

- Diego: deer

- Tadhg: dog

- Andy from Logophilius: dolphin

- Sydney: donkey

- Jack: duck

- Steele: eel

- Termy: emu

- Margareth: ferret

- Faux Frenchie: finch

- Keith: fish

- Laura: gaur

- Ignacio: gnat

- Kristofer: hamster

- Sonic Snejhog: hedgehog

- Kevin & Helen: heron

- Lyssa & Ayesha: hyena

- Luis: ibis

- Linguistic C̷̛̤̰̳͉̺͕̋̚̚͠h̸͈̪̤͇̥͛͂a̶̡̢̛͕̰͈͗͋̐̚o̷̟̹͈̞̔̊͆͑͒̃s̵̍̒̊̈́̚̚ͅ: kingfisher

- Joanna: koala

- Larry: lark

- Fiona: lion

- Chris L: loris

- gramaryen: marten

- Molly Dee: mole

- PharaohKatt: parrot

- Felicity: pelican

- Mignon: pigeon

- Tony: pony

- Rach: rail

- sam: ram

- J0HNTR0Y: stingray

- Stan: swan

- Amir: tapir

- Meredith: termite

- Nigel: tiger

- Wolfdog: wolf

And our newest patrons:

- At the Listener level: Narushi and Marty

- At the Friend level: Verena

- And our newest free members: Sascha, TwiksLinguistiks, Melissa, Laura, Sabrina, Matthew, and Vee

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

Democracy Sausage

https://democracysausage.org/federal_election_2025/

Trump signs executive order enforcing truck drivers must be proficient in English

https://abc7.com/post/trump-truck-drivers-president-signs-new-executive-order-enforcing-motor-proficient-english/16276745/

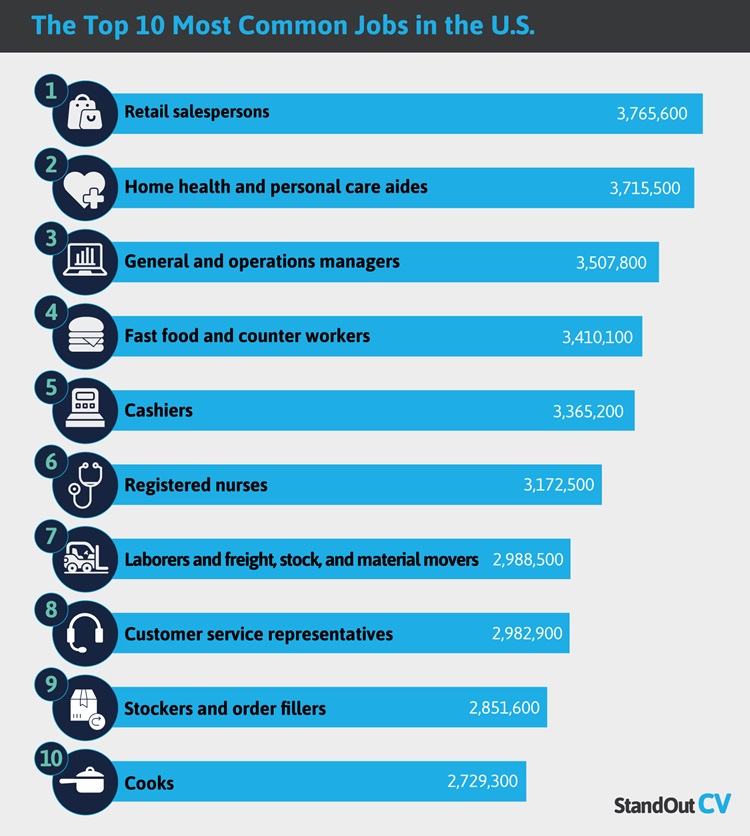

Most Common Jobs in America (November 2023)

https://standout-cv.com/usa/stats-usa/most-common-jobs-in-america

Children’s reading and writing develop better when they are trained in handwriting

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/04/250430142559.htm

The impact of handwriting and typing practice in children’s letter and word learning: Implications for literacy development

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2025.106195

The kerning on the pope’s tomb is a travesty

https://www.fastcompany.com/91324550/kerning-on-pope-francis-tomb-is-a-travesty

[$$] leprosy | The Oxford Companion to the Bible

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780195046458.001.0001/acref-9780195046458-e-0428?rskey=iEeb5y&result=428

10 Top Slang NYC Words from Yerrr to Brick (from 2 years ago)

https://nyartlife.com/the-10-top-slang-words-in-new-york-city/

Scientists Say They’ve Discovered a New Color—an ‘Unprecedented’ Hue Only Ever Seen by Five People

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/scientists-say-theyve-discovered-a-new-color-an-unprecedented-hue-only-ever-seen-by-five-people-180986473/

The Perils of Audience Capture

https://www.gurwinder.blog/p/the-perils-of-audience-capture

🎁 You’re Being Alienated From Your Own Attention by Chris Hayes | The Atlantic

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2025/01/attention-valuable-resource/681221/

God Spared Him Because Flock Raised $8 Million, Roberts Says

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-04-02-mn-1975-story.html

An Animated Demo of the Wagner-Fischer Algorithm for Sequence Alignment

https://calc.hypotheses.org/3265

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

DANIEL: Sorry, I’ve got to do pronunciation. Umeå is the name of the university.

HEDVIG: Umeå.

DANIEL: Umeå.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Umeå.

HEDVIG: If you want to sound a bit more local, you could even say Ume University. Daniel, if you want to come across as a bit like…

DANIEL: I would never presume.

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

Hello and welcome to Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. My name is Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. It’s Ben Ainslie. Ben, we’re recording this on the election day for Australia. And Laura on our Discord has mentioned democracy sausage. Ben, did you have a democracy sausage today and maybe explain?

BEN: My local polling place, which is to say primary school, because that’s overwhelmingly where it happens in Australia, had run out of democracy sizzle sausages by the time that I got there. But I, as a clutch backup play, I swung past a Bunnings to feel like I got my sausage. Yeah. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah, okay.

HEDVIG: Nice.

DANIEL: So, do we know…? Hedvig, should we explain what democracy sausage is?

HEDVIG: Yes.

BEN: Basically, it’s just sausage. It’s a hot dog. There’s really no sort of grander explanation than that. It is a sausage in a very cheap bun, usually with some fried onions and then your choice of condiments that you have applied to it. And it is available to you after you vote. And it’s usually run by the school parents and carers association. So, the money goes to the school, and they buy new gym equipment or something like that.

DANIEL: But it does contribute to a festive atmosphere. Voting in Australia, it happens on a Saturday. It’s compulsory, so everybody has to do it. So, you see everybody.

BEN: There are very few things that I’m proud of as an Australian, but the way we do elections is a thing that I am incredibly proud of.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Yep.

BEN: We fucking rule at voting. [LAUGHS] It’s so good, we’ve got preferential voting. It’s always on a Saturday. It’s all like… Yeah, no, we smash voting in Australia.

HEDVIG: Yeah. You’re pretty good at it.

BEN: We were lucky, I think. We did it last. That’s the reality. It’s like after everyone had fucked up and we had realized globally that, like, “Wow, first [UNINTELLIGIBLE 00:02:32] voting, fucking terrible.” And so, when Australia started doing it, we were like, “Well, what if we fixed all those mistakes?”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] We did. We did.

HEDVIG: No, it is very good.

BEN: Yeah. We’re very lucky in Australia. So, yeah, it was election day, which is always, I don’t know, call me a little bit twee, but there’s always a little bit of a vague civic like pride that comes on voting day. Having said that, I am on record as being like voting is not the best form of democracy and we should definitely move to democratic lotteries. But failing that, Australia does this pretty well.

HEDVIG: Democratic lottery?

BEN: No, we won’t, we won’t, we won’t. You’ll get me going for ages. At the end, remind me and I’ll explain.

DANIEL: And Hedvig Skirgård. Hedvig, I’ve got a question for you. What kind of democracy food would you like to see?

HEDVIG: Oh, so it has to be…

DANIEL: Democracy ravioli.

HEDVIG: It has to be cheap to produce, and it has to be easy to distribute, and it can’t be like a full meal. It has to be like a hot dog, a taco, like a…

BEN: It has to be on the go, like it can’t be a sit-down thing.

DANIEL: These are self-imposed constraints. [LAUGHS]

BEN: No, they’re not. They are constraints of the reality of the situation.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Yeah. And they technically don’t need to be savory. They could actually be sweet.

DANIEL: Yep.

HEDVIG: So, like a donut could be something. I do like…

DANIEL: Democracy donuts.

BEN: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: I’m a big fan of cinnamon rolls. I have one every weekend at a cafe I go to.

DANIEL: Oh.

HEDVIG: I think they’re quite easy to make. They can even be a little bit warm, but they don’t have to be. Easy.

BEN: Hedvig Skirgård, when you next find yourself in the same geographical location as me, let me make for you my cinnamon rolls, because I am.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah?

BEN: I’m going to say…

DANIEL: Ah, I’ve had these.

BEN: They’re better than nearly every bakery I’ve ever been to, including the ones that are “famous” for their cinnamon scrolls. Whenever I try them, I’m like, “mine’s better than this.”

DANIEL: Yep. Well, I would like to see some democracy fries with a side of liberty ketchup.

BEN: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: That’s what I want. But I like Hedvig’s idea a lot better. A fixture of our show has been Hedvig’s annual update of the Eurovision Song Contest, which we always love because there’s a surprising amount that you can learn about language from Eurovision. But even we were surprised at how much about language you could learn from Eurovision. We were surprised that you could get an entire university unit out of it. And we’re saying that because someone has. Right, Hedvig?

HEDVIG: Yes. So, we talked to two of the three course conveners at Umeå University who run the… I think the title of the course is Eurovision and Linguistics, or Eurovision and Languages. I forget the exact title.

DANIEL: It’s called Linguistics and the Eurovision Song Contest.

HEDVIG: Linguistics and Eurovision Song Contest. And we talked to Solveig and Paulette and they were so nice and it was so fun also for me to just… I would throw out a little trivia fact and I was like, “Was that Georgia?” And they’d be like, “Yes, it was.” And I was like, [LAUGHER] “Someone else knows what I’m talking about, and I am correct?”

DANIEL: Yes.

BEN: There is a uniquely fun feeling to find people as tragically into, or even more tragically into the thing you’re tragically into than you. There is a deep validation that happens when you’re just like, aah.

DANIEL: It’s true.

HEDVIG: I should say also that I like Eurovision and I like the way that they’ve done it. I like it as a lens to understand other things. So, when you watch Eurovision, you get a sense of how the different countries are portraying themselves. That’s very interesting to me. I kind of care less about the stage performance and… I don’t know, I care about it as a cultural spectacle and a way to understand politics and identity in Europe.

BEN: You approach Eurovision how I approach pro wrestling, which is to say, I don’t actually like it very much, but it’s fascinating.

HEDVIG: Yes, exactly. Which is why I also like… I mean, there are some years where I’ve been like, “I’m not sure I want to watch it. There’s a bad vibe this year,” as some previous years have been, for example. So, yeah, Eurovision nerds come in different flavors, but it was really fun to talk to them. And I don’t know what exact parts Daniel has cut because Solveig and Paulette and I sometimes [BEN LAUGHS] weird off a little bit, so we’ll see what he’s cut up.

DANIEL: Kept it all. Kept it all. Yep. So, we’ll be airing that chat with Paulette van der Voet and Solveig Bollig from Umeå University. Our latest episode was with Dr Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna about their book, The AI Con, where they document the current AI hype cycle that we’re living in. But our episode before that was a live episode for LingFest 25. We piled everybody in a room, voted on tough English usage questions. You can watch that and/or listen to that. If you wanted to be invited to bonus episodes and live episodes or just support the show, you can do that by becoming a patron. You can help us share the message of linguistic science and become part of a community of nerdy people who like language. Just head on over to patreon.com/becauselangpod.

BEN: Hey, Daniel, before we get into Eurovision, should we not check in with what’s going on in the world of linguistics?

DANIEL: Yes. This one was suggested by the Deliquescent Future on BluSky, also by Diego and Aristemo on our Discord. We’ve got a lot of people suggesting the story, which is kind of a shame because it’s about Trump and we do have a Trump band in effect, because it’s exhausting.

BEN: A Trumbargo.

DANIEL: A [LAUGHS] Trumbargo. We don’t want to talk about it all the time, but when it’s about language and when it’s kind of important, we sometimes will jump in. Like when the president made English the official language of the USA, we thought, “This is notable. We should talk about it.” So, the Deliquescent Future says, “Did you catch the executive order requiring truck drivers in the US to be fluent in English ‘sufficiently to converse with the general public’…

HEDVIG: Interesting

DANIEL: …to be enforced against currently licensed commercial drivers by unspecified measures.” Did we? Well, no, we did not. And so, that’s the story.

HEDVIG: Thank you, guys, for bringing it to us. I think it’s really interesting because… So, truck drivers is actually quite a common job in the US. I saw this map of the US states and what the most common job is. We can get into all the details of what counts as the same and different job. But truck driver is… a lot of people are truck drivers.

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: And a lot of people are foreign immigrants who work as truck drivers because they can drive a car and they can do the thing, but they might not necessarily speak English or for that matter, Spanish. I actually had a supervisor, a linguistics professor, who was interested in this because there’s been like a bit of rumors that there’s like a trucker pidgin.

DANIEL: Oh, right.

HEDVIG: That because there are so many different people speaking different languages and they sometimes need to get on those little sets and be like, “Hey, there’s a big boulder on this road,” and you go on the radio and you tell all the other ones so that they can safely navigate the roads and whatever. So, truck drivers often talk to each other on this radio. Maybe now, it’s all Bluetooth, Wi-fi, satellite, I don’t know.

DANIEL: Is that a CB radio? Is that what it is?

BEN: Yeah. Breaker, breaker.

DANIEL: 1/9.

HEDVIG: Something like that. But it makes a lot of sense that even if you work for different companies and stuff, you might want to be collegial and be like, “Hey, this is happening,” or like, “I’m behind you, but don’t worry,” or whatever.

BEN: I think even on a much simpler level, truck drivers just talk to each other as well, because it’s a boring job where you spend a lot of time just with not a lot to do.

HEDVIG: Right. This is why my mom, she went hitchhiking around the US in the 1970s, said that truck drivers are really good because they’re bored out of their minds and they’re going really far, and they’re like, “Sure, I’ll take you to Nevada.” And you can do that safely or unsafely, I don’t know if it’s possible to do. But anyway, there’s this idea that because a lot of them don’t speak the same languages, that they would have developed certain shorthand communication for common things to say.

BEN: Yeah, like Creole or something.

HEDVIG: Exactly. And that this could be understood as a pidgin in the same way that we talk about trade pidgins or war pidgins or colonization pidgins…

DANIEL: Or even space pidgins.

HEDVIG: But it’s sort of hard to get data on this. So, there were some people saying maybe this is happening. And there were some people in trucker forums online talking a little bit about the shorthand. But to my knowledge, no one’s done a research project on this. But if they’re all forced to have a high level of English, then yeah, they wouldn’t need this.

DANIEL: Well, here’s the background. This is kind of a revival of an old rule from 90 years ago. That’s right, July 1937. The rule was that truckers had to, A, be able to read road signs, B, communicate with law enforcement, and C, interact with employers and customers in English.

HEDVIG: I can see that.

DANIEL: Some reasonable things.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Up until the Obama years, there were loads and loads of infractions drawn up. A lot of people were also placed under a situation called out of service, which means you’re done. You’re not able to work in this business. In the Obama years, enforcement became deprioritized, and so those infractions stopped. But now, this is a revival of that. And it’s an executive order, which is not the same as a law. But executive orders do send signals, and people who are in positions of power will take that as a signal that if they wish to abuse the law or use the law very zealously, there will be no consequences for that.

And I was thinking, why trucking? But I think you’ve answered that question for me. This is a place where maybe a lot of people who don’t speak English work, and it’s a lot of people, is a sizable work group. And this is a chance to enable people in positions of power to fire people who are either English learners or not great at English or just simply not hire them.

HEDVIG: I think the question that’s important here is if there is an actual danger to road safety. Because if there is, I can understand wanting a solution, right?

DANIEL: Right. Well, I did do some looking up on that, and it seems that even in cases where there have been big accidents or bad accidents, the problem hasn’t been language. Language didn’t cause the problem, usually. It was lack of training or other things that can get you in trouble if you’re in the trucking industry, just from my lookups. Now, it’s not clear how this is going to be enforced. And my fear is because, of course, the Trump administration has a thirst for the worst, it’s probably going to take the form of arbitrary hassling of people who aren’t in the in group. But for people who are in the in group, they’ll be fine and won’t be affected by it at all. And the reason this is happening, I think, is because Trump is just that guy who hates having to press 1 for English on phones if he ever did have to. Once again, it’s rules for thee and not for me, rules that protect the in group, but punish the out group. That’s what I think is going on here.

HEDVIG: So, if immigrant truckers might not have jobs, they would need to be replaced by American-born English-speaking truckers who want those jobs. And what sometimes happens when immigrants are kicked out of certain fields is that some developed nations find that their own don’t want to do it. [CHUCKLES] So, this happens with like fruit picking, for example, where it’s like, “Okay, then we have no one to pick our avocados,” so it’ll be interesting to see how many… And I mean, it’s also possible that a lot of the immigrant truck drivers actually might meet this requirement. Even if they don’t speak English fluently, they could maybe meet these requirements. We’ll see. We’ll see what happens.

DANIEL: It’s anybody’s guess how much trucking will even happen once the coming economic slowdown happens. The tariff-induced slowdown.

BEN: Yeah, maybe all of the jobs that are lost are sort of like pretty much exactly how many fewer will be needed because the economy has shrunk.

HEDVIG: And also, when we talked to Carmen Fought, she also brought up that a lot of people who move to the US and who don’t speak English very well want to learn English. So, she talked about them doing these volunteer training sessions with people. So, people would travel far, but often they have a 9-to-5 job and a family. And they don’t have the resources, they can’t pay for the courses. They don’t have enough time. So, if this means that trucking companies are going to give classes in English to these truckers, that… I mean, I don’t know if that’s going to happen.

DANIEL: Oh, that’s a nice idea. Let’s find out if that’s what happens.

HEDVIG: We’ll see what happens.

DANIEL: Well, thanks to the Deliquescent Future and to Diego and Aristemo for bringing that story up to us. Here’s a question. When it comes to learning, what’s better, typing or actual writing?

BEN: Well, we have three educators on this show. So, I would imagine that we are all familiar with the evidence for this.

DANIEL: Well, spell it out because I’m a little fuzzy.

HEDVIG: I’m not.

DANIEL: Go for it.

HEDVIG: No, I don’t know the… I’m the one… I’m saying I don’t know a lot about… I’m bad at handwriting.

BEN: So, look, I might be about to eat a whole bunch of crow, but let’s see.

HEDVIG: Yup, let’s go.

DANIEL: Just tell me what you know.

BEN: My understanding is that there is substantial evidence to suggest that things like retention are significantly improved if you incorporate a substantial handwriting component to your learning process…

DANIEL: Really?

BEN: …or to put in a much simpler way, when you write stuff by hand, you do a better job at retaining it and remembering it.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: Why is that, do you think?

BEN: I suspect it’s because it’s slower and it operates at a speed that… This is not evidence based at all. This is just my supposition. I’ve always guessed or presupposed that it’s to do with the fact that you have to go quite slow when you write. Even people who write quickly, the fastest typers are much, much faster than the fastest writers unless you’re doing some weird journalism shorthand or something like that.

HEDVIG: Shorthand, yeah.

BEN: And I think for that reason, and because you are engaging not only the psychological process of like, “I want to spell words on a page,” you’re also doing like the mechanical and dexterous manipulation. Now, I understand that with a keyboard you’re doing that too, but I think… I don’t know, there’s just something about writing that hits different. For me, typing on a keyboard can exist sort of a little bit faster than conscious thought, whereas writing absolutely can’t, right? Like, writing happens slower than conscious thought.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. I mean, when you’re typing stuff on a keyboard, it’s the same motion, just in a different place, doot, doot, doot. But when you’re writing different letters. That’s a suite…

BEN: Yeah, exactly.

DANIEL: …of different movements. Mm. Well, this is some work from Dr Gorka Ibaibarriaga of Universidad del País Vasco in San Sebastián, Spain, and a team. This was published in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. They were working with 5- and 6-year-olds because they felt like that was kind of a critical time for writing. And they got the young ones to use the Georgian and Armenian alphabets, which they hadn’t seen before. And they would have to remember letters, sounds, pairings, and made-up words. And to practice, some of the kids used a keyboard and others had to actually write. And it turns out that, Ben, as you say, the kids that did better in the tests were the kids who had to physically write to practice. The team says, “Our work confirms that the graphomotor function is essential in memorizing letters and word structures.” So, it seems that doing the task with your body helps a lot.

HEDVIG: Do you think it also has to do with the breaking down of the character? So, for example, I’ve been doing like Duolingo Japanese and Mandarin lately, and it makes you practice the signs. And I also did Mandarin in high school, so I remember a bit of that. And it’s like, “Oh, well, it’s first this little dot and then there’s this line and then this one.” And you become intimately familiar with the internal structure in a way that when you type it, you do it all at once. Am I making sense?

DANIEL: It totally makes sense to me because I had the same experience. I had to learn Cyrillic handwriting, and I just did it for a long time and I can still remember it even though there’s so much Russian that I’ve forgotten, I spent so much time on Cyrillic handwriting, but I kind of surprised myself by still remembering automatically how it goes.

HEDVIG: Why did you learn Cyrillic?

DANIEL: I minored in Russian…

HEDVIG: You did?

DANIEL: …for my undergraduate.

HEDVIG: Oh, cool.

DANIEL: I did. Yeah.

BEN: I remember this. Yeah, I knew this…

DANIEL: Didn’t you know that about me?

BEN: …interesting little factoid and fact about Daniel.

HEDVIG: That’s cool.

DANIEL: Yeah. So, if you want to learn, if you want to be able to memorize, try getting in there and writing the characters instead… Well, now this is with different writing systeMs If you’re learning a language and you have to do a different writing system, try grabbing a pencil, not just typing.

BEN: I know I’m ever more drifting into this space of being like a… Not only a crotchety person but like a person who is like eschewing a lot of modern things.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: But there is, I think… going slow and finding ways to go slow is a thing that I think will be increasingly important for us as a society as our world gets ever faster and more sort of complicated and AI and blah, blah, blah, blah. And writing by hand is just a really effective break on stuff. You can’t go fast if you’re doing some sort of task where you have to write stuff out by hand. I don’t know. I’m looking for ways to slow down. And that seems like one of the good ones.

DANIEL: That is. Thanks. Let’s go on to our last news story. Pope Francis died recently, and people have noticed something about his tomb. It’s covered by a slab of marble on which is simply inscribed the name, Franciscvs. The U on the end of -us is a V, which is very cool, very classical.

BEN: Well, that’s just like all European architecture.

HEDVIG: [CROSSTALK]

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s like Roman.

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: But how to put this? It’s the kerning.

BEN: Oh, Daniel, are we doing font nerd stories? That what’s happening here? [LAUGHTER] I just need to share with everyone listening. We do this remotely, but we can see each other. And Daniel just had the cheekiest fucking grin when I asked that question. [LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Another fun tidbit about Daniel, besides the fact that he apparently knows a bit of Russian and Cyrillic, is that he’s designed fonts, which I knew about in theory, and then a year ago, I was using an app to do a thing, and one of Daniel’s fonts came up as an option, and I was like, “Ooh.”

DANIEL: Was it the Daniel font?

BEN: Was it the Daniel font?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: That was me.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: But, Ben, you might notice when kerning is really bad, and by kerning, I’m referring to…

BEN: [CROSSTALK] for being a font dork, but there is, unfortunately… what is actually happening here is I am not at peace with a side of myself which is also a closeted font dork.

DANIEL: You are trying to destroy that side of yourself.

BEN: Yes. Exactly.

DANIEL: Yes, I know.

BEN: So, please tell me about what font crimes have been writ large upon the marble slab atop Pope Francis’s corpse?

DANIEL: So, kerning refers to the space between letters in a word. If you put the same exact amount of space between all the letters in a line, it will sometimes look wrong.

BEN: Mm-hmm.

DANIEL: For example, the word, wave. If you have an equal amount of space between all the letters, it will look wrong because the W and the A need to be a little closer together to look right, and the A and the V need to be a little closer together so there’s not this massive hallway of space between them, this diagonal. You need to look at, not actual space, but visual space.

BEN: I hate to say it, but it’s about the vibes, man. It’s one of those things of if you do it…

DANIEL: It’s bad.

BEN: …exactly right, the vibes are all off. And then, if you just gussy it up and you get the vibes right, it feels like everything’s equal and it’s not…

DANIEL: Yep, that’s true.

HEDVIG: Or if you have what’s called a monospace font, where each character has the same exact space, people will think it’s programming because it’s popular…

BEN: Yes. Yeah. Yeah.

HEDVIG: …in a lot of programming UIs. So sometimes, when you see someone who just wants to say, “This is code,” they’ll use a monospace font.

DANIEL: I do that in my notes for my lectures. It’s true.

BEN: So, Daniel, what has happened to the tomb?

DANIEL: Oh, it’s not good. The word, Franciscvs, the F and the R just look like they are more widely spaced than the other letters and that poor A is absolutely stranded out there on its own.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: It’s done in Times New Roman, which is an unusual choice, but it’s very nice. It’s very understated, but somebody has clear… There’s an illustration in the story for this in Fast Company link in the show notes for this episode. But if you look at the illustration that somebody has made, you can see they’ve just placed equal space between every letter and it looks very, very wrong, which is unfortunate. I mean, if it were my slab, I would frigging get up…

BEN: Literally turning in the ground.

DANIEL: …unleash holy hell.

BECCA: Yeah. Yeah.

DANIEL: I would.

BEN: No, look, it does look, looking at the… I’m looking at the image now. It does look for listeners essentially, like there was a person called Anciscvs and they had some sort of job that was like a doctor, but like a fraktur. Because it just looks like F-R-anciscvs.

DANIEL: It’s Brother Anciscvs. Fr Anciscvs.

HEDVIG: In the interest of having not everyone agree, but also in my true opinion, I am looking at the thing and I’m going to tell you, dear listeners, it’s fine.

BEN: It’s not. She’s wrong.

DANIEL: Okay, tell them…

HEDVIG: It’s not that bad.

BEN: She’s dead wrong.

HEDVIG: It’s not that bad.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] This tells us about Hedvig and not about so much about the [CROSSTALK]

BEN: You can look at that F-R and you can say, “That looks like it’s part of the rest of the word,” really? I don’t believe you, madam.

HEDVIG: I just… Yeah, it’s fine.

DANIEL: Aengryballs on our Discord said, “I hope they redo it. At least turn the stone over and do it properly on the other side.” [LAUGHTER]

BEN: That’s fun, though. I kind of almost do wish they’d do that because that’s the sort of stuff that like a thousand years from now when they excavate something, because we find that, right? We find evidence of like, “Oh, I fucked that up. Here, I’ll flip it over and I’ll do it better on the top side.”

DANIEL: Yeah, just flip it over.

BEN: That’s great. That’s like a really fun humanistic thing for the aliens to find when they’re uncovering the evidence of our civilization.

DANIEL: That’s it. The aliens will say, “Oh, there must have been someone named Franciscvs.” And then, they’ll turn it over and see the fucked-up version. And they’ll be like, “Oh, yeah, fair. That’s shit.”

BEN: Or we can see that they had the capacity for rational thought at least.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Excuse me.

DANIEL: And some design sense.

HEDVIG: Or there’ll be Hedvig aliens who will be like, “Oh, they wrote the same thing on both sides. Slight differences. I wonder why they did that. Do they want the Pope to see his own name?” [LAUGHTER]

BEN: You’re right. You’re right. A space faring interstellar civilization is not going to have any attention to detail. They’re just going to be like, “Oh, these are basically the same.”

HEDVIG: Fucking fonts. Okay, sorry. [LAUGHTER]

BEN: This is so good. At the beginning of this story, I ceded my ground as like the hater of font dorkery. And Hedvig clearly was just like, “Hold my fucking beer. This is going to be amazing.”

HEDVIG: You must find.

BEN: “I’m coming in hard.”

DANIEL: And now, it’s time for Related or Not.

[LATEST RELATED OR NOT THEME]

DANIEL: Thanks very much to Hugh for our Related or Not jingle. All right, this one comes from Tigertronia on our Discord, who says, “Here’s a silly one. Rug and rugged.”

BEN: Ooh.

DANIEL: “I said, ‘Some of those rugs are pretty robust, I’ve got to say.’ But then, Aristemo added, “Wait, what about rag and ragged? All four related?” So, there’s your four, rug, rugged, rag and ragged. Some related, some not. What do you reckon?

HEDVIG: Rugged is more positive than ragged, right?

BEN: Yes.

HEDVIG: Rugged is like Aragorn, Strider in Lord of the Rings is rugged. Ragged is, you are also unwell and dirty and smelly and you’re not doing great.

BEN: I’m going to go… I’m putting my flag in the sand straight away and saying, rag and ragged are dead related. Ragged is just like, you are so shit. You are like made of rags kind of thing.

DANIEL: Made of rags. Yep. I could see that. That’s my guess too. But what about rug and rugged?

BEN: Rug and rugged. I’m thinking the age of those two words is going to be wildly different. I think rug potentially will be very, very old. And I think rugged is going to be a much more contemporary word, and therefore they will be unrelated.

DANIEL: Mkay. My flag in the sand is I can see rug and rugged, and I can see rag and ragged, but I’m not seeing a crossover.

BEN: Okay, okay.

HEDVIG: Okay. So, this is hard one. Who was it that sent this in?

DANIEL: It was Tigertronia.

HEDVIG: Okay. Very good job.

DANIEL: On our Related or Not channel. Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: I’m trying to do my usual sneaky move, thinking about other languages. [BEN LAUGHS]

DANIEL: That’s a good idea.

BEN: Way to be a polyglot.

DANIEL: Go Norse. Always good… You’re the only one who can help us.

HEDVIG: Right. Well, the back, like back of your body part, the back, where the pain lives. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: The nape.

BEN: [SINGING] Someone’s in their 30s.

HEDVIG: Yay.

DANIEL: The hackles. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: I may or may not have gotten a sort of massage thing for Christmas by my husband.

BEN: Oh, you got one of the guns? One of the [ONOMATOPOEIA]

HEDVIG: No, I got one that you put like here and you pull it and it does, like… Anyway.

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: Anyway. Okay. So, a lot of Germanic languages. Norwegian, Swedish, German at least back is [UNINTELLIGIBLE 00:29:29] or rygg.

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: And you wear rags on your back.

BEN: You’re going all fours.

HEDVIG: Yeah, I’m thinking… I’m going to go all four. And that there’s some sort of thing like a transitivity or perfectiveness or something that does the vowel shift, because that sometimes happens with fall and fell. Like, I fall, I felled you. They’re very similar, and the difference is like whether you do it to someone else as a transitive or a causative or perfective or something like that. So…

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: …I don’t know. I’m just going to say all related. Rag, ragged, rug, rugged, all the same origin.

BEN: If she takes this out, I think she’s earned the W on this one. This is a pretty good play.

DANIEL: Then, I found out that rugged used to mean back in the 1300s, having a rough, hairy, or shaggy surface originally of animals.

BEN: Oh, shit. Oh, dear.

HEDVIG: [GASPS]

DANIEL: They’re all four related.

BEN: Oh, well done.

HEDVIG: Yes.

BEN: Well done.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] They’re all probably related. All from Proto-Germanic, rawwa, meaning something like a shaggy tuft or a coarse coverlet or something like that. Also rough, likely related.

HEDVIG: Right.

BEN: Really? That’s interesting.

DANIEL: Thanks to Tigertronia and to Aristemo for that one. That was great. Next one’s from Michael, who wrote in and said, “Hello, my dear podcasters, big fan of your show, though just a lurker, till now. I have a suggestion for related or not. This might be an obvious one you’ve already covered,” we haven’t. “Here it is. Attic, the part of a building below the roof versus Attic related to Athens.”

HEDVIG: Oh, Attic Greek. Yes.

DANIEL: Yes.

HEDVIG: Right. I have to say I struggle with the word “attic” because I need to remember which one is which, because you have these attic and cellar and…

DANIEL: Oh, that’s interesting.

HEDVIG: I have to remember [CROSSTALK].

DANIEL: I never had that trouble.

BEN: I never heard the second sense before right now. So, yeah, to be of or related to Athens.

HEDVIG: I think they’re spelled exactly the same, A-T-T-I-C.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: So, what do you reckon? I thought I will recuse myself because I know this one.

BEN: Which would suggest that it is related if Daniel knows it. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Maybe.

HEDVIG: Or that it’s a common thing people think, and he knows that it’s not.

BEN: Yeah, true, true, true.

DANIEL: Yes.

BEN: I’m going to go with not related because they seem just, like very… oh, unless, unless…

DANIEL: Unless they had them. Unless they had a lot of them back there.

BEN: No, no, no. What I’m thinking is Greek architecture, classical architecture has that real squat triangle at the top of all of the pantheons and that sort of thing. And attics…

DANIEL: The frieze.

BEN: The frieze. And the attic kind of has that shape, like it’s under the roof of the. Ooh. It’s a stretch though. I’m going to go not related.

DANIEL: It does.

BEN: Not related.

DANIEL: It does. Okay, Hedvig, are you going to pull out the second one?

HEDVIG: Attic and attic. The Greek thing and the thing… I live in an attic flat. That’s why I have a diagonal roof behind me.

DANIEL: Yes, you do.

HEDVIG: I think they’re going to be related. They’re spelled too similarly.

BEN: Meaning the same? Like, they have [CROSSTALK] [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: The same. Which isn’t always a clue, but the longer they are, the more it’s a clue, usually.

DANIEL: Yeah. You can get away with rug and rag being different.

HEDVIG: Yeah, I think it’s one of those Corinthian, Dorian architecture terms that we get from Ancient Greek, and therefore, they are related somehow.

BEN: Ah.

DANIEL: Mm. Okay, well, Hedvig is on the right track once again because there are attic columns all over the place. The meaning jumped from the column to a triangular facade that the column supported, and then it jumped to the space up there.

HEDVIG: Ooh.

BEN: So, I actually had… I had the exact right answer. I just didn’t back myself.

DANIEL: It was in your hands. But they are totally related. And Hedvig wins the second one.

HEDVIG: Wow.

DANIEL: Michael continues “Your collective combo of erudition and seemingly effortless banter.” Oh, effortless, he says.

BEN: [LAUGHS] Until that is after Daniel has had his editing ways with the show.

HEDVIG: Also, I’ll have you know, I love recording process with you, and I love all of you, but sometimes when you make me get up very early in the morning. I’ll record podcasts and I’ll be very effortlessly bantery, and then I go lie down for two hours, actually. [LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Same. Michael says, “Your seemingly effortless banter, no doubt the result of tremendous effort and experience and editing is beyond compare. Thank you so much for your tireless advancement of language nerdom.” Michael, you say tireless, I’m kind of tired.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: There’s tire. Tire exists.

DANIEL: Okay, I’m giving you this next one. This next one comes from me because I wondered. The word is so. So means a lot of things. So means to such an extent. It was so big. It’s a conjunction. I was finished, so I left. And it means in addition, as in also. Are they the same so?

BEN: Oh, okay. So, we’re not even talking about putting plants in the ground or putting fabric together. We’re just talking about the same spelling.

DANIEL: S-O, that’s all.

HEDVIG: And then you have the even so and just so, which are arguably variants of the three categories you described earlier, maybe?

DANIEL: Something like that.

HEDVIG: This is where it gets hard, because it’s a short one, isn’t it? It’s just two sounds.

DANIEL: So, the first one is. The first one is to such an extent, so big. The conjunction, “I was finished, so I left,” shows a result. And then also, in addition.

BEN: I going to go with all related. Because it feels like one of those times where we’ve just kind of lazily used one word just to do a lot of heavy lifting.

DANIEL: That’s what we do with efficient units, but Hedvig is not sure.

BEN: Yeah, she seems pensive.

HEDVIG: No, I’m doing the. I’m doing my…

BEN: I’ve got to check on a cat, one sec.

HEDVIG: I’m doing my checking other languages. So, both German and Swedish have very similar extents, of something that looks very similar. But that could just mean that those things existed in like Proto-Germanic or they borrowed from each other or something. It’s not necessarily… So, [UNINTELLIGIBLE 00:36:19] I drank a lot of water, so I have to go to the toilet. Yeah, it’s some sort of prepositional, locational thing that means like “to the extent of” or something like that is my theory.

DANIEL: Yep. Okay. So, what do you reckon?

HEDVIG: Yeah, all related.

DANIEL: Do you think they’re the same?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay. You’re both correct. They are all related. Now, here’s the unifying sense. When you say that something is so big, you’re saying it’s big in such a way. That’s how it is. The so as in the result, “I was finished, so I left,” it’s sort of like you’re saying I was finished and things being in such a way as that, I left. Now, Etymonline also points out that these come from an Old English word, swa. In fact, sometimes we even see swa-swa, [UNINTELLIGIBLE 00:37:12], like as. So, this was a word that grew into so, but it was frequently strengthened by eall, all

BEN: Eall?

HEDVIG: Yeah, also.

DANIEL: Which is all. And so, also is sort of like “all being in that way” and it is contained in compounds.

BEN: I never realized how hard it would be to explain a word to my mind, as simple as so to a non-English speaker.

HEDVIG: Mm-hmm. It’s hard.

BEN: Like I’m hearing Daniel try and do it and I love you, Daniel. You do a great job. But even you were kind of floundering a little bit.

HEDVIG: Yeah, it’s hard.

BEN: it’s not an easy word to explain at all.

DANIEL: I worked on that explanation all afternoon. [LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Really? Yeah. No, that’s a good… I can tell. The smaller they are, the more frequent they are, the more vague, abstract their meaning, the harder it gets. Ask anyone to explain… There’s a bunch of German terms like mal and doch and a bunch of other ones that like…

DANIEL: Doch is great.

HEDVIG: You just have to be exposed to it a lot, [UNINTELLIGIBLE 00:38:10] very vaguely, right?

BEN: It’s another vibe check situation.

DANIEL: Yeah, it’s a vibe check. You mentioned this, Hedvig. If we made a big list of all the words in English from most common to least common, at the bottom, we would have a bunch of really long words with specific meanings like microphone and antipathy. Whereas at the top of the list we have all these tiny words that just don’t mean anything until you start putting them next to other words. Amazing. Well, that’s it. So, this was one of those where they were all related, every single thing. Congratulations to Hedvig, but you both did a great job. Thanks to everybody who’s giving us these ideas. If you’d like to donate a jingle to us, you can go ahead and send that, hello@becauselanguage.com. We’re loving the ones we’ve gotten. And thank you to Hugh for yours.

[MUSIC]

[INTERVIEW BEGINS]

DANIEL: We’re talking to Paulette van der Voet and Solveig Bollig of the Umeå Universitet in Umeå, Sweden. They are heading up a university class about language called in English, Linguistics and the Eurovision Song Contest. Hello, Paulette and Solveig. Great to see you.

SOLVEIG: Great to be here. Thank you for the invite.

HEDVIG: Yes. So, how happy are you that you… This is the first semester you’re offering this course, is that right?

Solveig and Paulette: No, it’s the second one.

HEDVIG: Oh, second.

DANIEL: Oh, that’s the time when you go through and fix all the problems.

HEDVIG: Are you…? The intake for the students was before Kaj 1, right? So, okay, okay.

DANIEL: Sorry, the Kaj?

HEDVIG: Are you feeling the Kaj…?

DANIEL: Sorry. So, you’ve got to… I’m the noob here. You’ve got to help me.

HEDVIG: All right. What usually happens on this show is that Daniel says a bunch of stuff about like Americans. He’s like attorney general and 401k and like tri-state area or something. And I have to be the European to be like, “I don’t know what those things are.” So now, I get to do the other thing.

DANIEL: I’m the audience surrogate now.

HEDVIG: So, the Eurovision Song Contest is an annual contest in which different countries compete in who has the best song.

DANIEL: I knew that.

HEDVIG: And you vote and there are juries and it’s all very complex. And it’s run by the European Broadcasting Association. I think I’ve got that right. And in every country, the broadcaster who is a member of that association gets to pick how they select their representative. And in some countries, it’s all done in like backrooMs Like, the BBC selects for UK. And it’s just a bunch of people, they go into a room and they pick someone, more or less. Whereas in Sweden we like to do it as big as we can. So, we have…

PAULETTE: Yes.

HEDVIG: …first a preselection filter by some jury specialist. And then, we have four contests and then everyone who gets first on that one goes to the final. And everyone who goes second goes to another contest called Second Chance before the final.

DANIEL: Cool.

HEDVIG: All in all, you have six weekends of the spring, late winter, spring, who are just like Eurovision mania.

DANIEL: That sounds amazing.

HEDVIG: Some people think it’s amazing. Some people think it’s over the top. There are different opinions.

PAULETTE: But it can be both.

HEDVIG: It didn’t used to be this big, but this year the contest was won by a group from Finland. So, in Finland, the east parts of Finland and also south and the island between Finland and Sweden, there are people who speak Swedish natively in their communities. They speak what we sometimes call Eastern Swedish dialects. And I would call them a music comedy group from Eastern Swedish speaking dialect, entered into the Swedish contest and ended up winning.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: So, I think they’re Finnish citizens. I don’t know if they’re also Swedish citizens. I’m not actually sure.

SOLVEIG: No, they’re just Finnish citizens.

HEDVIG: Yeah, but they do speak Swedish natively and I think they speak Finnish with like a Swedish version of Finnish as well. Anyway, it’s very exciting because we’re coming up on the next Eurovision contest. If Sweden wins this one, then we have the most wins ever.

DANIEL: Oh, exciting.

HEDVIG: And it’d be really exciting. I personally think it would be really fun if that was with the group, Kaj, because they feel humorous and lighthearted and not this kind of like serious pop, whatever Måns Zelmerlöw was doing this year. You guys are nodding. Okay, so we’re on board. Anyway, the thing, Daniel, that you have to understand is that Kaj is like… So other European countries are understanding this as well, it’s very exciting. And they’re going to compete in Swedish. They’re not going to make an English version of their song for the big contest. And that’s unusual.

DANIEL: For some reason, that sounds like it means something, but I guess it’s time to bring in Paulette and Solveig. So, what’s your… [HEDVIG LAUGHS] Where are you? Are you both just like massive Eurovision nerds like Hedvig is?

SOLVEIG: We all were separately big Eurovision fans and then we all started our PhDs together and started to watch Eurovision Song Contest together. And obviously, if you put a bunch of linguists in one room watching Eurovision together, it’s all we talk about, the language choices, multilingualism. So, we always thought that we should do something with that. And we kind of ended up designing an entire course around that.

PAULETTE: And we thought that the department would never accept it as a course. [DANIEL LAUGHS] We thought we would get a no somewhere in the system, but we didn’t get a no anywhere. And we went ahead and we taught it for the first time last summer.

HEDVIG: I think it’s a brilliant idea. And also, I know that a lot of university departments… How to say this. So, like at the Stockholm University, there’s a summer course on dinosaurs that looks like it’s very airy and fun and it gets a lot of students, but it’s actually a serious paleontology course, but it gets a very high student involvement. And I think using something that looks very poppy and trendy, you can actually use it as a great focal lens to actually talk about things.

I understand one segment of the course is, for example, about language policy, which is really interesting to explore through Eurovision. So, I think it’s very smart. And I’m not surprised that Umeå University approved of this because I think it’s like a smash hit.

PAULETTE: I mean, we have also great national examples. Linnaeus University had a couple of courses, for example, with vampire focus, and it was basically just Gothic literature, but it was sold as something different. I mean, it’s so great to catch students with something so special and so popular and then just kind of get in some actual content.

DANIEL: The problem is evaluation.

HEDVIG: But it’s a serious course. It’s this credits and exams and evaluation and everything like that, right? They have to read papers. They have to pay attention during class. You’re not just showing up to a room and playing YouTube clips of your favorite Eurovision winners.

PAULETTE: No. We were a bit concerned. We thought that some students would think that’s exactly what we’re doing, but everybody was on board with our vision, and we got a lot of really, really interesting final exaMs So, we are very happy with how it turned out.

DANIEL: Wow. But you don’t want to flunk Eurovision. That would be too terrible. [LAUGHTER] Let’s take a look at the linguistic areas that your unit touches on, because there’s a lot going on here. Where do you want to start? What area stands out to both of you?

PAULETTE: Maybe the first module. Your module, Solveig?

SOLVEIG: Yeah. So, my module is mostly on basic linguistic concepts. So, we have a big part on language versus dialect, prestige and so forth just to make sure that everybody who may not be all too familiar with linguistic concepts is on board.

DANIEL: Let’s go right there. Tell me about prestige in language as it shows up in Eurovision. What goes on? What’s an example you might use?

SOLVEIG: I mean, then we’re already in language choices. What languages are presented as Eurovision and which are maybe not so common? Then, we can go back to Kaj. Swedish hasn’t really been all that popular, especially among Swedish-speaking public. So now, we have Swedish back on the menu. But Swedish hasn’t really been all that big of a prestige language in the Eurovision contest at all. And I also think it hasn’t really been a prestigious language among Swedish speakers.

DANIEL: Why not?

SOLVEIG: I think the associations for Swedish is it’s a bit too cute. It’s a bit too funny for a serious competition. It doesn’t sound all that serious. And I know that non-Swedish speakers might disagree with that, [DANIEL LAUGHS] but I think the associations from Swedish speakers are a lot in that line. Like, if you want to compete seriously, it can’t be in Swedish.

PAULETTE: And when you want to win.

HEDVIG: Exactly. That’s the problem. I don’t know, Daniel, if you understand this, but, like the Swedish contest is so much geared towards winning Eurovision to the degree that people will vote tactically, so they’ll like put their vote on not who they think is the best in the final, but who they think that the rest of Europe will vote for.

DANIEL: Oh.

HEDVIG: And this means that very often the person who comes like second is actually the one that people actually enjoy and they’ll get the most streams on Spotify or whatever, but the person who wins is like the bland thing that we think most Europeans will accept.

DANIEL: Disappointing.

HEDVIG: It is. I find it very disappointing. I think that’s also why people have not been wanting to put forward entries in Swedish, because they think, “Well, Serbians and Spanish people are not going to vote for a Swedish act,” which is a bad way of thinking about it, because some of the things that do the well is like the campy, funny, local, regional stuff, right?

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Like, what’s the Ukrainian woman called? [SINGING] Ein, zwei, drei, dancing doo, doo, doo.

PAULETTE: Verka Serduchka.

HEDVIG: Thank you. That’s like some of the best Eurovision you’ll ever see. And that’s like, how many languages in that song? At least two, if not three?

PAULETTE: Yeah, I think it also has to do… I mean, Sweden is the third largest exporter for popular music. So, I also think Sweden views the Eurovision Song Contest as some kind of card for the rest of the world to see what we can do. So, I don’t necessarily think that Sweden wants to be present in the Eurovision Song Contest as representing the country but rather representing the music industry in Sweden.

HEDVIG: Oh, okay, so it’s like Max Martin industry we’re representing, rather than… Mm.

SOLVEIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: In that case, which languages are considered the high prestige languages? Paulette, what’s your assessment?

PAULETTE: For a long time, it has been English, and especially if we look here in Sweden, as soon as they were allowed to participate in English, they did participate in English. They were one of the… I think they were the first country that participated in another language than one of the national languages. Because when Eurovision started, they were like no language rules. And it took some time before the countries figured out that there were no language rules. And when Sweden did, they did it very successful. And since then, as long as they have been able to participate in English, they have more or less been participating in English. It’s even so that songs that have been like winning the national selection in Sweden in Swedish have been translated into English for the Eurovision stage. So, this is very new.

But on the same time, there is like kind of a border in Europe between Northern and Southern Europe, where Northern Europe, English has a lot of prestige to participate with a song in English at the Eurovision Song Contest while in Southern Europe we see that the national languages have a lot of prestige.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. Okay.

SOLVEIG: The Romance languages, for example, speakers of those languages are more likely to compete in their national languages. Same goes for Southern Balkan region. So, there are specific regions that are more likely to compete in their own languages. But then obviously, we also see a bit more general trends apart from English. French is a relatively high prestige language, as well as Italian. For a while, a couple of countries were also participating with partly in Russian or partly in German, but that hasn’t been really all that visible in the last couple of years for understandable reasons. So, we also see a bit of a shift of what is considered prestigious or not.

DANIEL: Spanish is the party language.

HEDVIG: Can I ask? Should we discuss…

HEDVIG: Daniel, you’ve got me. That was exactly what I was going to say. We’ve advanced before in this podcast the theory that sometimes countries where Spanish is not an official language will sing a song in Spanish, because Spanish is the party language. And if you’re doing like a party song with like a rapid beat and you have a lot of dancers on stage, you sing in Spanish even if you are like… who was it that did it? It was one of the Balkan nations that did it recently.

SOLVEIG: It was Romania a couple years ago that…

HEDVIG: Yes, it was Romania.

DANIEL: Great to have these two. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: So, do you agree with our Spanish as the party language theory?

SOLVEIG: I think it’s a party language, but it’s also very much tied to specific music genres. If you’re competing with an Americanized country song, you’re not going to sing in your national language. And I think the same also goes for party songs or Latinized songs. Then, you’re more likely to compete in Spanish or a Romance language.

DANIEL: It reminds me a bit of what happens in… Someone described the situation India when it comes to official languages or the languages that get used. If we make it Hindi, then Telugu speakers get mad and other speakers. If we make it this language, others speak… So, English might not be most people’s favorite or the language that most people feel comfortable in, but it’s considered to be an acceptable middle of the road choice. Is that kind of a situation in Eurovision if you’re going for broad appeal?

PAULETTE: We can also see that English songs have been doing very well among the juries for a long time. And the jury vote has been very important in the beginning of Eurovision, and it has been changing. The public vote has become more and more important and more and more present at the contest. And we see also that there is a difference between… The jury vote is often going to songs in English, while the public vote is often going to songs in other languages than English. So, we also see that happening.

HEDVIG: Mmm. And can I ask, since you’re two Eurovision experts, like, what is the reason for the jury vote? Is it just because we think the masses have poor taste and they need to be reined in?

SOLVEIG: I mean, in the beginning it was simply a practical choice. Like, in the 1950s and 1960s, you can’t just ask the public what they think and conduct that in a timely manner. That’s just not possible. But in most juries, it’s music industry professionals, it’s people from the individual broadcasting services. So, they obviously also have a kind of vested interest in what becomes popular.

HEDVIG: Sure.

SOLVEIG: Personally, I don’t really think that the jury does all too much. I think that has also been a contentious point the last couple of years, that there is a really big difference between what the jury wants and what the public wants. And I think the public doesn’t view the jury votes too favorably right now.

HEDVIG: No, yeah, it does feel… I understand what you said, like the Eurovision Song Contest has been going on since 1965?

SOLVEIG: 1956, Yeah.

HEDVIG: Oh, swap around the numbers, 1956. And of course, you couldn’t call in or click on an app and have everyone do it within certain amount of hours, but you can do it now.

SOLVEIG: Yes, we already see a change there. Like, the semifinals rely on purely the public votes right now. That’s a change that has been made in 2023, I believe. So, we do see a change in the voting system, and I think it’s probably only going to be a matter of time that we are just not having these jury votes. But at the same time, it’s a great show to have the national spokesperson announcing the jury votes. It’s a part of the thing that makes Eurovision, Eurovision. I think in that case, we would have to find another solution for that, because I do think that most people still want to have that kind of suspense of having a spokesperson announcing the points.

DANIEL: You mentioned that Russian has been a language that has been selected by many singers, but for understandable reasons, as you say, this is no longer so. And it sounds like geopolitical tensions have an impact on the languages that people use for their songs. Are there any other examples that you can think of or that people have brought up?

SOLVEIG: One big example is, of course, Ukraine. Ukraine had a streak where they basically just sent English-speaking… English songs. And since the Krim invasion in 2014, there haven’t been any songs purely in English. There have been a couple of songs with English and Ukrainian lyrics. But, I mean, that’s also a big, big, big thing to publicly show your national identity, especially if that national identity is being questioned.

The same goes for the Balkan regions. The ex-Yugoslavian states have been more likely statistically to participate in their own language, simply because you kind of have to show that you have a language, that you have a singular national identity. So, there definitely are geopolitical trends and there are geopolitical forces that kind of play into the language choices.

HEDVIG: Yeah, for sure. So, when you talk about the language policy part of your course, do you also discuss language policies outside of Eurovision in the countries in general? So, for a while, for example, it was only the case that you could participate in Eurovision with a language that was an official language in your country. And not all countries have official languages or have something… Different kinds like minority, minority or sign languages are in a weird category sometimes. So, in your course, do you talk about that as well?

SOLVEIG: We do. Obviously, we do have a focus on Sweden. So, we’re talking a bit about the Swedish minority languages. But we also have a second module which is purely multilingualism and minority languages that Paulette has been teaching.

PAULETTE: Yes.

DANIEL: Oh, well, then let’s talk about that for a second. What’s going on with minority languages? They’ve been on the rise, haven’t they?

PAULETTE: They have always been present at the Eurovision Song Contest. Like, there is often one song with like either parts in a minoritized language or completely in a minoritized language. And we have seen that for many years. Sometimes, it’s just like a couple of words. We have had Norway in the 1980s participating with a song with the title in North Sami, but the rest of the song was in Norwegian or English… In Norwegian, I think, yes. And so, we always have had a presence of minoritized languages, and I would really like to see them more at the Eurovision stage than what we see them now. But it’s not that it’s getting more, it’s not increasing. That’s not something that we see.

DANIEL: Do they win though?

PAULETTE: I can’t… Jamala had parts in Crimea.

SOLVEIG: In Krimtataren, yeah. And I mean, Norway a couple of years ago, with parts in North Sami, they did pretty well. They didn’t win, but I think they ended up second place. So, they come up close but winning? Yeah.

HEDVIG: So, on the international stage, singing or having a reference to a minority language or culture, is that another way of representing your country, if you understand what I mean? So, like, there are not Sami speakers in so many different European countries. So, Norway, by having some Sami in their entry, are sort of saying, “Oh, this is a part of being Norway as we have this as well.” Is that sort of how it works on that stage? Because people in, like, I don’t know, Montenegro won’t know Norwegian or Sami, [LAUGHS] so it’ll be equally foreign to them.

PAULETTE: So I think that when it comes to the song that I mentioned from the 1980s that Norway sent, Sámiid ædnan, that was a bit more special because the 1980s has been a very important period in Norwegian and Sami history when it comes to the Sami getting a voice and a place in the nation state of Norway with huge protests amongst others. So, it had a certain political load that time. Well, nowadays, when we look at like more recent contributions, the one that Solveig mentioned, I think that it has almost like a feel of a kind of exotification to show like, “This is also us and we’re also fronting this.”

SOLVEIG: We’re more different. Yeah.

DANIEL: The question I wanted to ask was, are the majority languages steamrollering the minority languages? Are they crowding them out or do you feel like they’re giving them a chance to shine? What’s your view?

SOLVEIG: Probably a bit of both. We do see different attitudes in different countries. We also see differing attitudes depending on what year we’re looking at. Italy, for example, they always send or try to send the winner of Sanremo Song Festival. And they recently had a change in the guidelines and the rules. So, the song has to be in Italian with a cover song in either Italian or English also performed at the festival. And previously, they allowed for dialects as well. And now, they have a guideline that says it’s not supposed to change the general Italian character of the song, which I have no idea what that’s supposed to mean in the context. I’m going to assume that they try to further a unified Italian national identity…

DANIEL: Mm, okay.

SOLVEIG: …but I find this change really weird, and I don’t really know what to make of it. So, I do think that it really depends on which year, which country, there’s differing opinions basically in every year and in every country.

PAULETTE: And we should also maybe say that the EBU, they have at this moment, no language rule. You can participate in whatever language you will. We have even seen constructed languages at the Eurovision stage. But yes.

HEDVIG: Netherlands, Iceland, who else?

PAULETTE: Belgium.

HEDVIG: Belgium, right.

PAULETTE: Two times.

HEDVIG: This is so fun. I’m usually the only one who knows. [LAUGHTER] I’m enjoying this.

DANIEL: Which conlangs were used? I don’t even know.

PAULETTE: Belgium had, for example, completely made-up language and I think the Netherlands as well. And the idea when Belgium for the first time participated with constructed language, the idea was normally that it’s either the Flemish broadcaster, so from the Dutch-speaking part or from the French-speaking part, sending it alternating years. And the idea was then, like, we sent this year a song in neither of our national languages. So, there are a lot of different motivations behind it.

DANIEL: Okay.

PAULETTE: And the EBU doesn’t have a language rule right now, but the broadcasters in the different countries selecting the songs, they might have language rules. For example, Italy, what Solveig mentioned. But for example, there are also countries, for example, Netherlands, they don’t have a language rule. It’s completely free choice of language. So, it depends a lot on countries, or not even on countries, but on the broadcasting unions participating what they are sending.

SOLVEIG: As with here, the Swedish broadcaster, for example, they say that they aim to have 30% Swedish-speaking entries in the national selection process. I mean, 30% is not a lot if you compare it to, for example, Italy where it is mandatory in Italian, or Iceland where all but the final have to be in Icelandic. So, it’s a big difference depending on the country and the broadcasting service.

HEDVIG: I think what’s really interesting talking about the Eurovision language policies of things is that Eurovision I think becomes a very nice mirror or like way of viewing how nation states are building their national ideology and identity. So, by allowing more different languages or something, you’re saying something like, “Oh, we’re…” I don’t know, “Either we’re so secure that we’re so monocultural that we don’t mind if someone does something different,” or, “We’re trying to build a multinational multiethnic state. So, we would love to have different representatives.”

And it’s hard to remember, I think this is going back very far, but Germany and Italy… so, the big five are Spain, France, UK, Germany, and Italy. And they get to participate regardless of how good their contributions do in the first filter, which is sort of why they tend to send maybe not the best entries [LAUGHTER] because they don’t have much selection process. But Germany and Italy I think stands out a little bit among them as… how to say, they’re kind of the youngest countries in that group. Do you know what I mean? Like, Italy only unified in like, what is it, 1850? And Germany is barely a coherent country now. It’s just a bunch of prince city states that sort of stuck together. And then, some of them became like Switzerland and oh, god, all my German friends are going to listen to this, but I think they know what I mean. [LAUGHTER]

And also, Italy also speaks a language that has a high prestige, but it’s not spoken very much outside of Italy. Like, French is spoken in West Africa and Quebec. And Spanish is spoken all over the world, but Italian isn’t. So, maybe they feel, I don’t know, a bit more fragile about their cultural identity outwards and that’s why they’re enforcing these rules that has to be Italian. Does that make any sense?

SOLVEIG: Yeah. I mean, our Italian colleague also suggests that it might also be just a recent change due to the political climate in Italy right now, that it is very nationalized right now, that it is supposed to be a unified Italian strong state, and that can be true as well.

If we look at German, for example, I think it’s really telling that Austria has participated with several different dialects and Germany has not. Germany has only participated with standard German songs. So, I also think that might be an indicator that, “No, we don’t really need the diversity within Germany right now. We are barely unified as it is.” So, I do think that there are certain identity-building characteristics to be found, yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah, I’m not a specialist on German language by any means, but just living here, I think that Germans are quite sensitive about… They seem to be quite keen on removing some dialects. I live in Saxony and the Saxon variety of German is famous for being the worst one. Actually, I learned an interesting thing. An Austrian friend of mine, apparently in children’s cartoons the villains are often speaking Saxon German.

DANIEL: Oh, there’s a choice.

HEDVIG: And he grew up with this… Yeah. And he grew up with these cartoons and he said that he didn’t know until he moved to Saxony that it was a real dialect that people spoke. He thought it was just what villains spoke on TV, which says something about how they’re treating… I don’t even know what that would be in Swedish. I think it would probably be Stockholm dialect for villains, just picking on the capital is a popular thing to do. But yeah, I’m not surprised to hear that the German entries, if they are even in German, are in like standard High German or whatever. Okay, bit shame.

DANIEL: Let’s move on to gender and how that’s performed because language is a proxy for a lot of things about ourselves, national identity, but also gender. What have you noticed in how this is showing up?

SOLVEIG: What we can see is that songs about either sexual identity or gender identity tend to be in English simply because they appeal to a different subset of the public. I don’t think songs like that would be all too popular within a language just because it is just a subset of the entire European public that is supposed to be talked to.

HEDVIG: Mm. So, like the Austrian entry, Phoenix, was in English.

SOLVEIG: Yeah. Or like Switzerland’s winning contribution last year, Nemo, The Code, with nonbinary identity is also in English. And that’s something we do see that they tend to be in English or songs about questioning one’s identity or very universal topics, grief, identity finding, they do tend to be in English because they are so universal and they are meant to appeal, yeah, to a broader public.

HEDVIG: Right. So, you sing in your not English language, [CHUCKLES] lack of a better word. When you want to say something about your country, your culture, or a part of your country or part of your culture.

PAULETTE: Or more about traditional love.

HEDVIG: Yes. And even if you want to say something like, what’s that with the Polish entry with the butter?

SOLVEIG: Oh, yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Butter?

HEDVIG: Yeah. Or the Grammys, they…

DANIEL: Butter, you said?

PAULETTE: They were churning butter on stage. And it was fun. Everyone enjoyed that.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Oh, yeah, okay. I understand that gesture. Yes.

PAULETTE: Right. Or like if you have a bunch of babushkas on stage, if you want to appeal to like an older version, like something like pre-, I don’t know, 1950s of your countries using in your national language. But if you want to talk about gender or war, well, the Crimean Tatar one was partially.

SOLVEIG: Yeah, but I mean, the setting, the context, the setting, the stage was in English. So, I do think if you want to talk about difficult topics such as war, for example, English is a good medium. It’s just more understandable for a broader public.

HEDVIG: Do you think that sort of steamrolls the… I don’t know. So, from a broader perspective, for example, I’ve been thinking about this, and again, I’m not a specialist on this, but, for example, in lots of different countries, there are like different kinds of gender identities or sexualities that don’t map one-to-one onto like a sort of actual Anglo-American understandings. Like the term, queer or trans or bi or something, there might be like another sort of kind of identity that’s a bit similar but doesn’t map one to one. But then, as a lot of English cultures spread around the world and talking about these topics, sometimes maybe that eradicates that kind of divers… Do you guys know what I mean?

SOLVEIG: Yeah, I understand. I mean, obviously it’s also hard to map if you don’t really understand the language or the specific cultural context. So, I wouldn’t want to really say one way or the other, but I do think… I mean, people do have the choice to sing in another language if they really want to or if the broadcasting member allows for it. So, I think it’s probably more of a question of how the broadcasting union sees it, if that is something that is supposed to be expressed in English or in a national language, for example.

HEDVIG: So, if you sing in your national language about something that concerns your country, if someone doesn’t understand you, they minimally understand that you’re representing your country by the choice of language. So, in a sense, they kind of get a little bit of the meaning of the song just from the choice of language. But whereas if you want to talk about grief or love or sexuality or identity, you don’t think you can communicate that well enough if you don’t speak English.

PAULETTE: Or you want to approach like a larger public with it, and you want to appeal to a larger public with it, and you think that public that you can appeal with it is outside of your country.

HEDVIG: Yeah. Yeah, there’s a minority of people who are not straight in all countries, and there are few people maybe in your country, but if you add them all up across the countries, there’s more of them, but they’re all from different countries. So, what do you choose? English. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah. Okay. I’m sort of seeing how this works. The choice of language is a tricky topic. What are you signaling? Who are you trying to appeal to? What’s the topic? What’s the audience? Mm, you also have a section in your unit about metaphors. And, of course, metaphors tell us a lot about what we’re trying to communicate. Of course, metaphors of love, very common. What do we notice from the lyrics? What have your students pointed out?

SOLVEIG: Our colleague is not too impressed with Conchita Wurst, Rise Like a Phoenix anymore. I think she has read 15 essays with the same topic.

DANIEL: Oh, no.

PAULETTE: And students were completely free to choose any song they wanted to write about.

HEDVIG: Maybe next time they’ll not allow that song.

SOLVEIG: That was her thinking as well. Yeah.

HEDVIG: Fair enough. [LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Well, then give me an original one, one that was off the beaten track.

SOLVEIG: Off the beaten track.

DANIEL: What do you teach when it’s metaphor time?

PAULETTE: I think we can think a lot about Israel in the past years with a lot of metaphors about the war going on. Then, we can also see that metaphors are often used to convey a political message. Well, Eurovision, one of the rules that the EBU has is that it has to be an apolitical contest. So, to hide the political messages, we can often see that metaphors are used.

DANIEL: Okay, that makes sense. What’s an example?

SOLVEIG: Last year, for example, there was a huge controversy about Israel’s entry because it was originally called October Rain, clearly referencing the Hamas attacks in October. And they had to rename the song and called it Hurricane but basically left the entire meaning as it was. So, it was still understandable, if you looked at the lyrics, that it clearly was associated to the political situation in Israel and Palestine.

HEDVIG: But you can do something… So, there was one of the Balkan countries that tried to participate with a song called We Don’t Want to Put In or something, which is a pun on Putin.

DANIEL: Putin, yes.

HEDVIG: Who was it? Was it Georgia?

SOLVEIG: It was Georgia in 2009. Yeah. [LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: [UNINTELLIGIBLE 01:17:20] And that one, I think, was disqualified because they were like, “This is too obviously political.”