First words and last words get a lot of attention. But how did words get to have such a place of prominence? What would we see if we focused on interaction instead? A new book looks at words, gestures, and silence at the beginning and end of life. Daniel has a chat with the author of Bye Bye I Love You, Dr Michael Erard.

Timestamps

- Cold open: 0:00

- Intros: 1:05

- News: 6:59

- Related or Not: 35;54

- Interview with Michael Erard: 47:56

- Words of the Week: 1:33:32

- Comment: 1:45:46

- The Reads: 1:49:43

- Outtake: 1:56:01

Listen to this episode

Video

Patreon supporters

Thanks to all our patrons! Here are our patrons at the Supporter level.

This time we are ordering the names using the Scream Cipher from XKCD. It’s a substitution cipher in which every letter is replaced by some variant of A with a diacritic, and it just looks like screams.

https://xkcd.com/3054/

I used a very nice tool called the Scream Cipher Translator made by Matthew Watkins

https://scream-cipher.netlify.app

and then I alphabetised it

and your position in the list depends on that.

- Andy B (Aâa̲a̦ Ȧ)

- Andy from Logophilius (Aâa̲a̦ a̮ȃåǎ Ăåa̋åa̯a̰ảăảäã)

- Alyssa (Aăa̦ããa)

- Aldo (Aăa̲å)

- Amir (Aǎảȃ)

- Ariaflame (Aȃảaa̮ăaǎá)

- Ayesha (Aa̦áãa̰a)

- Amy (Aǎa̦)

- Elías (Áăíaã)

- Nasrin (Âaãȃảâ)

- Nikoli (Âảạåăả)

- Nigel (Âảa̋áă)

- Sonic Snejhog (Ãåâảa̧ Ãâáa̓a̰åa̋)

- Stan (Ãāaâ)

- Steele (Ãāááăá)

- O Tim (Å Āảǎ)

- sæ̃m (ãæ̃ǎ)

- Tony (Āåâa̦)

- Termy (Āáȃǎa̦)

- Tadhg (Āaa̲a̰a̋)

- Laura (Ăaäȃa)

- Luis (Ăäảã)

- LordMortis (Ăåȃa̲Ǎåȃāảã)

- Larry (Ăaȃȃa̦)

- Linguistic C̷̛̤̰̳͉̺͕̋̚̚͠h̸͈̪̤͇̥͛͂a̶̡̢̛͕̰͈͗͋̐̚o̷̟̹͈̞̔̊͆͑͒̃s̵̍̒̊̈́̚̚ͅ (Ăảâa̋äảãāảa̧ A̧a̰aåã)

- Lyssa (Ăa̦ããa)

- Manú (Ǎaâú)

- Molly (Ǎåăăa̦)

- Margareth (Ǎaȃa̋aȃáāa̰)

- Meredith (Ǎáȃáa̲ảāa̰)

- Mignon (Ǎảa̋âåâ)

- Wolfdog (Ȁåăa̮a̲åa̋)

- Whitney (Ȁa̰ảāâáa̦)

- Rach (Ȃaa̧a̰áă)

- Rene (Ȃáâá)

- Rodger (Ȃåa̲a̋áȃ)

- Ben (Ȧáâ) is here

- Kevin (Ạáàảâ)

- Kathy (Ạaāa̰a̦)

- Kristofer (Ạȃảãāåa̮áȃ)

- Keith (Ạáảāa̰)

- Ignacio (Ảa̋âaa̧ảå)

- J0HNTR0Y (A̓0A̰ÂĀȂ0A̦)

- Jack (A̓aa̧ạ)

- Joanna (A̓åaââa)

- Chris L (A̧a̰ȃảã Ă)

- Chris W (A̧a̰ȃảã Ȁ)

- Canny Archer (A̧aââa̦ Aȃa̧a̰áȃ)

- Colleen (A̧åăăááâ)

- Felicity (A̮áăảa̧ảāa̦)

- new this time! Faux Frenchie (A̮aäa̽ A̮ȃáâa̧a̰ảá)

- Fiona (A̮ảåâa)

- PharaohKatt (A̯a̰aȃaåa̰Ạaāā)

- Hedvig (A̰áa̲àảa̋) is here

- Helen (A̰áăáâ)

- Diego (A̲ảáa̋å)

- Daniel (A̲aâảáă) is here

- gramaryen (a̋ȃaǎaȃa̦áâ)

And our newest patrons:

- At the Friend level: Mary

- And our newest free members: Jana, Sabine, F. W., Max, Oliver, Sarah, Emily, doğukan, Pterrorsaurus hex, and Emily

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

Lunarbaboon

https://www.instagram.com/lunarbaboon

[🎁] Gore Vidal Dies at 86; Prolific, Elegant, Acerbic Writer

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/01/books/gore-vidal-elegant-writer-dies-at-86.html?unlocked_article_code=1.6k4.vzhR.IErb2fqqb5rC&smid=url-share

Did You Know: Using Swear Words In Google Search Disables The AI Function

https://says.com/my/tech/swearing-at-google-searches-breaks-its-ai-feature

“Just give me the f***ing links!” — Cursing disables Google’s AI overviews

https://arstechnica.com/google/2025/01/just-give-me-the-fing-links-cursing-disables-googles-ai-overviews/

Language prediction in monolingual and bilingual speakers: an EEG study

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-57426-y

Whalesong patterns follow a universal law of human language, new research finds

https://theconversation.com/whalesong-patterns-follow-a-universal-law-of-human-language-new-research-finds-249271

[$$] Whale song shows language-like statistical structure

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq7055

Zipf–Mandelbrot law | Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zipf–Mandelbrot_law

Bye Bye I Love You: The Story of Our First and Last Words, by Michael Erard

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262049429/bye-bye-i-love-you/

https://www.penguin.com.au/books/bye-bye-i-love-you-9780262049429

Michael Erard, 2023. Beyond Last Words: Patterns of Linguistic and Interactional Behavior in a Historical Sample of Dying Hospital Patients. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, (86) 3.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228211000938

‘Coffee Badging,’ New Coping Trend To Get Around In-Office Mandates

https://www.forbes.com/sites/bryanrobinson/2023/09/29/coffee-badging-new-coping-trend-to-get-around-in-office-mandates/

Jingle Halal Song | TikTok

https://www.tiktok.com/discover/jingle-halal-song

ahmedlovesbread,

Muslims don’t celebrate Christmas but some of us are in “Jingle Halal Mode” which means we will accept your invitation to your Christmas party to drink your eggnog and eat all the gingerbread cookies you can offer. My karaoke song is “rocking around the Christmas tree” (Brenda Lee version, all the others suck)

https://www.threads.net/@ahmedlovesbread/post/DD49Of2y715

What is a Dunkelflaute?

https://www.next-kraftwerke.com/knowledge/what-is-dunkelflaute

Scream Cipher Translator

https://scream-cipher.netlify.app

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

BEN: This is one of those boring bloke things to know. I think the sound of the various laser weapons in Star Wars were created by hitting high tensile wires that keep like radio towers up and stuff. Like, that cool sound you get when you go like [MAKES ZAPPING SOUNDS]

HEDVIG: It’s so funny as well how it’s warped our perception of things. So, like frying pans, it’s like rain.

BEN: Rain. Yeah, yeah. We don’t. We don’t like the sound of rain. We like the sound of bacon.

HEDVIG: Yeah. And it’s just like, what are we even doing?

DANIEL: I like listening for the Wilhelm scream. That’s my sound. [LAUGHTER] [IMITATES A WILHELM SCREAM] Let’s try to get in one Wilhelm scream in this episode.

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

DANIEL: Hello and welcome to Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. My name’s Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. We’ve got the wonderful Hedvig Skirgård. Hello, Hedvig.

HEDVIG: Hello. Good morning.

DANIEL: And the scrumptious Ben Ainslie. Hi, Ben.

BEN: Hello.

DANIEL: As you both might know, I’m teaching a first-year linguistics class and it’s my first one in a long time and I’ve forgotten everything about teaching. So, I need your advice. What do you think I should convey to new linguistic students or what about them should I try to bring out? What’s your advice?

HEDVIG: Usually, the first semester is about half on learning sort of normal norms and prescriptivism and just be like: linguists aren’t language police. We study the thing. We don’t moralistically try and judge you and enforce the thing. So, usually the first semester, in my experience, is that’s the big part.

BEN: Okay, but it’s so freeing.

HEDVIG: It is so freeing.

DANIEL: It is.

BEN: That weight falls off your back and you’re like, “Wait, you can do whatever?” And the linguist teacher is like, “Nah-uh.” And you’re just like, “Oh, this is amazing.”

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Thank you, Hedvig. Ben, from your perspective, what do you reckon I should be doing out there?

BEN: Oh, I don’t know.

DANIEL: You can even give me really bad advice so I could try the opposite of what you would do.

BEN: Yeah, true. I could do that. I don’t know. I feel like I probably just want to crib line Lunarbaboon or something like that, where you would just be like, “Look, you can go through your life being an asshole or not, so choose not,” which is basically like a colloquial version of exactly what I just said. But it’s just kind of like: Just be chill, man. Just go into the world curiously and look around and be like, ‘Well, that’s interesting. Well, that’s interesting too. Well, that’s interesting.’ Instead of going, ‘Oh, I don’t like that. I don’t like that. I don’t know.’

DANIEL: That’s really beautiful.

HEDVIG: But that said, a lot of the people will come out the other end and maybe go into, like, I don’t know, language teaching or speech therapy or something. And we should say, like, While there might not be a moral like right or wrong, there is such a thing as successful and unsuccessful communication.

BEN: Yeah. [LAUGHS] For sure.

HEDVIG: Like, my last attempt there. And it’s good to have some sort of… But to come at it with what Ben said, like a curious, positive, interesting attitude rather than a… yeah.

DANIEL: Thank you, both. On today’s show, we are talking to author Dr Michael Erard. He’s the author of a new book, Bye Bye I Love You: The Story of Our First and Last Words.

HEDVIG: Ooh, that’s sad.

DANIEL: I have this idea that we never know what the first word a baby says ever is because…

BEN: We don’t understand it.

HEDVIG: Yeah, we don’t know that that’s a word.

DANIEL: Yeah, we don’t understand the first thing they intend. And also, when we do hear a word, we hear random garbage and say, “Oh, that was a word. I recognise that.”

HEDVIG: Yeah. We have both false positives and false negatives. They’ll be like, “Blah, blah, blah,” and it’s like that is what they’ve said repeatedly for milk and we didn’t get it. And then, they’ll say,“Blah, blah,” and we’ll be like, “Oh, that’s lamp 100%.”

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Famous first word, LAMP.

HEDVIG: In Swedish, it’s surprisingly common, I think, because I think babies lying, looking up, they will often point at lamps and be like, “Pitha lampa,” I think it’s like not the first, but it’s like relatively…

BEN: Your people experience a lot of darkness as well.

HEDVIG: It’s the thing in the ceiling that we know that the kid sees and they’re lying down with their head up. Like, I don’t know.

DANIEL: I’ve been planning my last words, but I haven’t decided what they’re going to be yet. So, that’ll be something to look forward to.

HEDVIG: Oh, my god, you’ve been planning your last words?

BEN: You should do something super tragic and poetic like Einstein. And have the person who’s with you not speak the language that you speak so your last words are like lost forever.

HEDVIG: [MOANS IN BACKGROUND] Oh, no, just do something stupid like mundane and cute.

BEN: Like what? What’s something mundane and cute for last words?

DANIEL: Like, what? I need an example.

HEDVIG: Like, um… “Did you open the dishwasher?” Something like…

DANIEL: That’s mundane.

BEN: That’s mundane.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: That’s kind of terrible because then your partner’s like: the last thing he said was: I needed to open the dishwasher. I haven’t stopped thinking about it.

BEN: One of those relationship vexations that after like 65 years together just never goes away. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: No. Or like, “Did you already do the cat boxes?” Something just like a thing you often say, that’s just… Maybe that would be worse. I don’t know. I don’t know what you’re supposed to say when you die! I don’t… [SIGHS]

BEN: I think GOODBYE seems like a pretty solid choice.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Right. Versions of goodbye. Yeah.

DANIEL: Gore Vidal’s partner — maybe this wasn’t his last words — but he said, “Didn’t it go by awfully fast?”

BEN: Aww.

HEDVIG: [WHIMPERS, BREATHES HEAVILY]

BEN: We’re really bumming Hedvig out! I can see her little face being like [ONOMATOPOEIA]

HEDVIG: Yes.

DANIEL: It’s okay, Hedvig. We’ll be okay. We’ll focus on first words. There we go. Babies! Yay.

HEDVIG: All right. Okay.

DANIEL: Did you know that we have a shop where you can get Because Language stuff?

HEDVIG: I do.

DANIEL: Where you can get our Because Language mug and our Grammar Grass design. And now, we have the Linguistic Chaos Goblins. Yes, that’s right. They’re doing their thing. They’re causing trouble. You could be them. Buy one, buy them all. Oh, and hello to whoever just bought our Buffalo-Buffalo sticker. That’s fun.

HEDVIG: That’s cute.

DANIEL: So, you can find all of our great designs on our shop becauselanguage.com/shop, so shop.

BEN: But, Daniel.

DANIEL: Yes. Yes, Ben.

BEN: I have felt bereft of linguistic news. I’m jonesing for a fix, Daniel. Have you got what I crave?

DANIEL: I’ve got what you need. [LAUGHTER] Let’s talk about Google’s AI results. Is anybody else annoyed by Google’s AI overview that pops up when you search for stuff?

BEN: I found myself, against my better intentions…

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Whaaat.

BEN: …using it.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: As in, well, see, here’s the thing. Like, it is dark UX design, isn’t it? Because it’s there. I don’t get a choice. At least I don’t think so. I probably can turn it off, I haven’t looked into that yet. But the answer comes up and I’m like, “Oh, I mean, that was the answer that I was looking for. I guess I don’t need to click on anything.” And I’ve been doing that a bit, but it makes mistakes.

DANIEL: Yes, it does.

BEN: I was just playing Baldur’s Gate 3 with my partner. And I was looking at how to… This is a very deep cut, nerdy thing. But I was like, “Hey, you should totally do like a potion of fire immunity.” And my partner was like, “No, that’ll get rid of my strength buff.” And I’m like, “Mm-mm. Google says no, it won’t.” And then, she did it and it immediately got rid of her strength buff. And I was like, “Well, that showed me to learn to trust the machine.” Boo.

HEDVIG: I have also reluctantly been looking at it, but this little questions that it makes, like you ask something and then it’s like, here are some questions that are related. They’re kind of funny to see in the same way that it’s fun to see, like when you start typing, you see the search possible searches. And she’s like, what are other people…? What is this semantic space like? What are other people doing? And sometimes, the questions are very off and the answers sometimes are also quite off from those questions. It’s fun to see what the neighborhood is.

BEN: What about you, Daniel? How have your searches fared?

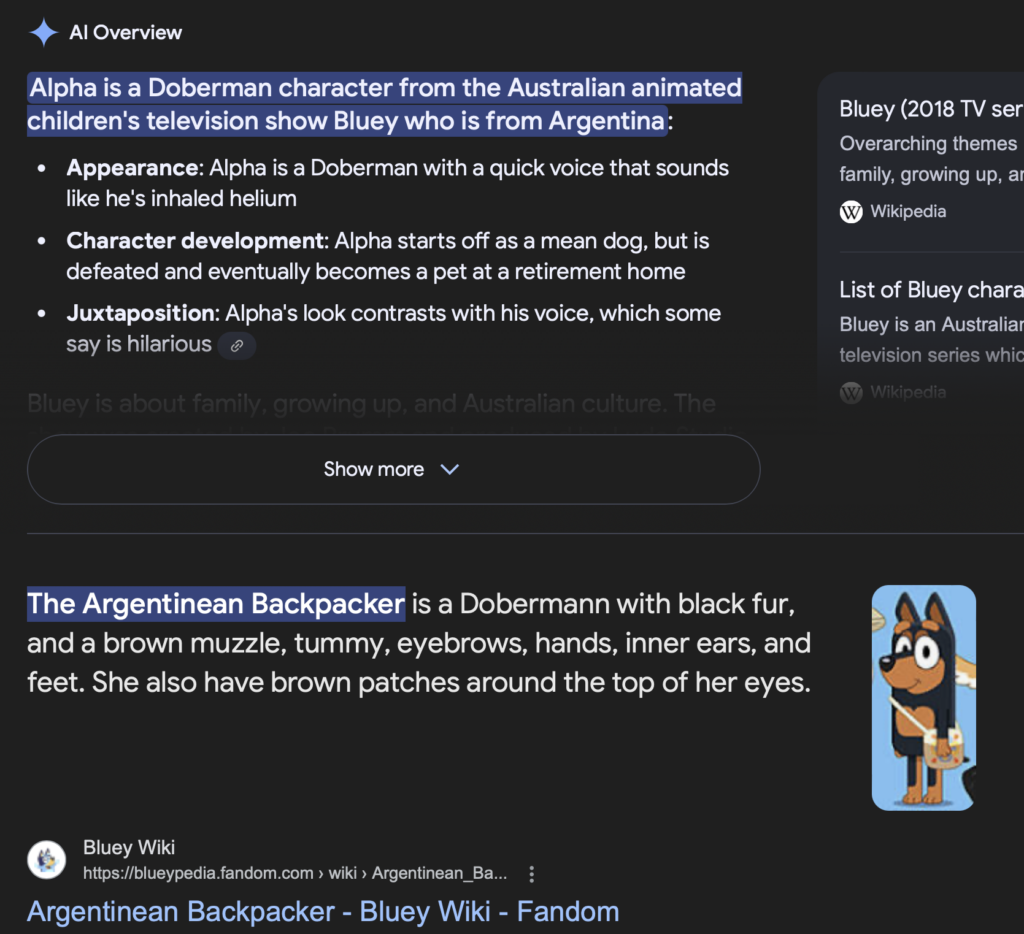

DANIEL: Well, I decided to test it on something that I know pretty well, which is Bluey. There’s an unnamed character in the episode of Explorers, and she’s a Doberman, a backpacker from Argentina. So, I looked her up in Google. I said “Argentine backpacker, Bluey, Explorers.” And the AI overview says, “Alpha is a Doberman character from the Australian animated children’s television show, Bluey, who is from Argentina. Alpha is a Doberman with a quick voice that sounds like he’s inhaled helium.” And it just goes on and on, it’s all wrong. The character doesn’t have a name. She’s just the Argentine backpacker. So, make sure that you test it on something that you know pretty well.

HEDVIG: Yeah,

DANIEL: Well, Ben, you said that you didn’t have a choice, but…

BEN: Well, I quickly amended that to realise that I was mostly just speaking from a place of laziness and that I probably do have a choice. So please tell me how I was immediately wrong.

DANIEL: Okay, well, we’ve spoken before about how to take Google back to a more sleek, stripped-down profile using &udm=14. That’s right, &udm=14 to every search you do, because that is just plain old basic mode. That’s the code for that.

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: u-d-m.

BEN: &udm14. All one string, no spaces?

DANIEL: &udm=14, and it’ll just take it right back, but that’s hard to remember. So now, there’s an easier way. Any swear word will do it.

BEN: [LAUGHS] Oh, that’s great.

HEDVIG: Really? Oh my god. I’m going to try it now. Okay, I did &udm=14 and that did work. Now, I’m going to try… I’ll try every Australian’s favorite curse word.

BEN: I was just going to suggest that. Yes, yes, do that.

DANIEL: So, this is being reported on Ars Technica and other places around the web that if you include a swear word, then it will not give you AI search. I’m also finding that if you do minus, like, if I do, “How do I change a tire -spaghetti?” — and that’s what you do if you don’t want it to give you any results with the word spaghetti in there — it doesn’t give you spaghetti; it answers your question. But it also doesn’t give you AI Overview.

BEN: Okay, cool.

HEDVIG: You’re right. It doesn’t do a overview. It does do the questions. They seem to be independent. Interesting.

DANIEL: Okay, interesting. I can believe that. Why do you think swearing would turn off AI Overview? Any ideas as to what it’s thinking?

HEDVIG: Because it doesn’t want to swear. It doesn’t want to say swear words.

BEN: That’s a much better way answer I came up with… In the same way that our phones turn spellcheck off when we go all caps, in my head, it’s because the phone is just like, “You know what, man? I’m just going to let you run with this.”

DANIEL: You have this.

BEN: I feel like when you drop the C bomb in a Google search, Google just kind of goes, “Uh, I’m going to take a step back. I’m going to let you… Whatever’s going on for you, it seems like a you thing.”

DANIEL: It’s true. Google’s Gemini AI system tries to avoid swearing if it can. So, if you give it taboo language to deal with, now you’re throwing it into a zone where they have to monitor whatever it is more carefully and they just act with caution.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: I really… As fun as this is that instead of remembering a logic string that you would attach to the end of your searches, you can just drop a swear word. And as punk as I think all three of us like to be around how we use language and that sort of thing. I still don’t love the idea, say, that at my workplace, should anyone look through my searches, there is just going to be this litany of inappropriate stuff going on. It’s not… It’s like… I’m sure I could explain my way around it, but at the same time, it’s like [ONOMATOPOEIA]

DANIEL: I didn’t know Mr Ainslie was as angry as that.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Yes. It could be, right? [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Well, in that case, just go minus spaghetti.

BEN: Minus spaghetti, indeed.

HEDVIG: But then you have to remember where the H is in SPAGHETTI in English.

DANIEL: Okay. Don’t say SPAGHETTI. Make it something else. Make it RIGATONI.

HEDVIG: No, I’m just being…

DANIEL: I don’t care. Just pick any Italian food.

BEN: Hedvig brings up an incredibly valid Ben-Ainslie barrier to that solution.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Placement of H’s is hard.

DANIEL: Well, that’s easy. First, you just type “how do you spell spaghetti”.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Let’s go on to our next story. This one’s from you, Hedvig. You mentioned this one, but I’m going to drive, and then I’m going to let you jump in when you’re ready. Is that cool?

HEDVIG: Yes.

DANIEL: Okay. We’ve talked on the show before about how our brains are prediction engines. As we listen to someone speaking or we watch somebody signing whatever it is, our brains are always making little predictions about what’s coming next? What’s coming next? And we can do that because we have absorbed a lot of language information, especially the transition probabilities of words, sounds, and syllables. That is to say, given the language that we’re getting, we have a super good idea of what’s…

HEDVIG: …coming next.

DANIEL: …coming next. And that helps us make the job a little easier. It shaves a little time off of our response. It means we have to choose between less things in order to understand. It’s super useful, and it’s something we do all the time.

BEN: One of the things that, in my job, I notice about this is that for people who don’t necessarily speak publicly, very often it is, in my opinion, and purely anecdotally, the leading cause of error in public speaking. Essentially, they say a prediction that isn’t correct. So, they’ll be reading something, and they’ll stuff up because they’ve gone to say what they thought was coming next instead of what’s actually on the page. This is something that I see all the time with teenagers, but I suspect for adults as well, because not everyone is like all three of us, like do the talky-talky on a podcast and also do the talky-talky in our professional lives in front of people. So, for a lot of people, it’s not a thing that they do, and so, when they do it, they’re like [ONOMATOPOEIA] whereas we’ve all practiced to overcome it. You almost have to fight against your prediction tendencies when you’re reading and speaking publicly.

HEDVIG: But are you talking about reading aloud?

BEN: Yes.

HEDVIG: Yes, okay. Yes. Because I feel like reading aloud — I don’t have children — but I have read children stories at bedtime and I’ll read something and I’m like, “I don’t enjoy the structure of that sentence. I’m going to reshuffle a little bit. I don’t like how this author did this.”

BEN: [LAUGHS] Just subediting on the fly.

DANIEL: They’ll never know.

HEDVIG: Don’t you do that?

BEN: No. [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: No? You read exactly what the book says?

BEN: I follow the rules! You know, I’m not telling you what I do.

HEDVIG: Oh, my god. Wow. Do you read a lot of modern books? Because I find the older stuff, like there’s a classic Swedish kids’ books from my hometown, Uppsala, the book is, Pelle Svanslös, is a little cat that doesn’t have a tail. And it’s written in like the early 1900s, and I don’t think it’s good prose, and I just restructure it on the fly. I’m just like, no.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, fair enough.

DANIEL: I found that Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne still works in lots of ways, but it does have a different feel. It’s got slightly different transition probabilities. Okay, but now I want to focus on what if you speak more than one language?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: You’ve been trained on more than one set of data and you might think that different things are likely. Does this work differently? And I want to focus especially on word, surprisal. Will bilingual listeners be more surprised by upcoming words than monolingual speakers? What do you think?

BEN: I anticipate, yes, they will. That’s my guess.

DANIEL: Seems logical.

BEN: And we’ve got like a quadlingual here, so this is going to be a really fun thing to test.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s a good question. Hedvig, your subjective experience on this?

HEDVIG: So, I know the paper we’re going to talk about, and I know what they found.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: And I was not surprised by what they found. I also think that the differences kind of maybe don’t come into play in something else than an experimental setting. I don’t feel what’s… when it’s unexpected code switching. So, Ste said a Swedish word the other day that there’s an English… So, there’s a Swedish word, RIENT, and there’s an English word RENT. And I didn’t know which one… I didn’t know what language he was saying it in.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: And that stuffs me up. So, like, false friends and not knowing when you’re switching into which language does definitely delay my processing. But if I know that it’s English all the time, I’m like, “Next word is going to be English,” then I feel like I do similarly to a monolingual. I don’t know.

DANIEL: Well, let’s get to the study then. This is from Mohammad Momenian of Hong Kong Polytechnic University and a team, published in Scientific Reports. Before we get to the results, I just want to… I’m going to ask Hedvig, I’m going to ask you for the results, but let me just talk through what they did. They were using ERP, event-related potential. This is a kind of research where you look at someone’s brain activity after a stimulus and see what’s going on.

In this case, they were looking at N400, that is to say, 400 milliseconds after a stimulus. Like, when you get an unexpected word, what happens 400 milliseconds afterwards? And it’s 400 because that’s a point of interest in language processing. If you get a weird word like, “I take coffee with cream and dog,” then that’s the point at which your brain’s going to go bloop. So, Hedvig, did they get what Ben expected?

HEDVIG: So, what they got was that they found that… First of all, they found that there was a difference between their monolingual speakers and the bilingual speakers in these exercises, which is interesting in itself that there’s a difference at all.

DANIEL: I’ll just say the language of the study was Persian.

HEDVIG: Yes. And people were monolingual, and there were bilingual Persian experimental subjects. And they found that bilingual speakers were a little bit delayed, that monolingual speakers were sensitive to both the surprise effect from the current and the previous words, whereas bilinguals were more concerned with the immediate previous words.

DANIEL: Oh, so the bilingual speakers were surprised by the last word, but not the word before that, because they couldn’t take that wide a window of context into account.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: So, in other words, they were surprised just like the monolinguals, but slower. It took them a little longer to get surprised, and they were mostly surprised by just the previous word if that was weird or unexpected. But the monolinguals, they could be stumped by two previous words.

HEDVIG: Yes. They say, for example, bilingual speakers engage in predictive processing, but there’s usually a delay observed in the effect. This delay could be explained in terms of a processing deficit. Now, this is where it gets into tricky because there is, in this experiment, a little bit of a delay. But if this is detectable only in experimental conditions, like super controlled environment and EEG and you get milliseconds, if this is actually detectable in any kind of like normal day to day activities is I think a bit unclear.

There are already people who think that bringing up your kids bilingual is going to be bad for them. And if there is a delay and a cognitive processing deficit, that makes that scarier. That’s just why I want to coddle it in like there is a difference, but we don’t know how much it actually…

DANIEL: Matters.

HEDVIG: …like, it’s going to matter in a day-to-day conversation.

BEN: I mean we have a word for this, right? In parlance, which is to say this issue is academic.

DANIEL: It’s a distinction without a difference.

HEDVIG: But it might not be. I find it hard to… I’m looking at whether…

BEN: Academic… I don’t necessarily think means is like an… is a dig or an attack. It’s just saying… I think an acknowledgement of exactly what you’re articulating, which is the lived experience of everyday people would not find this in any way relevant, interesting, useful, etc., which I mean we should not relegate academic inquiry and pursuits to that. We should definitely be asking questions that extend beyond the relevance to everyday people. But what you’re acknowledging, or at least what I’m suggesting we can say is that this study has found something of academic significance but potentially very little everyday user person experience.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: But there is a difference which is interesting. There’s a difference for these people for this task. And the difference, we’re talking tinies.

DANIEL: I notice also that they said there’s strong evidence for effects of education frequency of the previous word, and neighborhood density of the previous word. And that just means how many words sound like the previous word. Like, if there’s the word PAT, you’ve got AT and SPAT and BAT and those things sound the same and that could throw people off too.

HEDVIG: Yeah, that’s the other thing. There are a lot of other things that have an effect on this too. So, they mentioned as well that different… They didn’t control in this case for things like working memory, processing speed or inhibition, which other studies have shown an effect on just a set of monolingual speakers. So, there are a lot of things that have an effect on this predicting next word. Not all of them are whether or not you have other candidate languages in your head.

DANIEL: Mm. So, is this anything? Interesting result or meh?

HEDVIG: I think it’s interesting. I think it’s interesting that there’s a difference. I think it sort of certainly makes a bit of sense. Like, if you have more candidates to pick from in your head, maybe it takes you a little bit of a longer time to retrieve them. I’m a little bit surprised that you already hear language A, language A, language A, language A, and you’re supposed to predict the next language A word, and I feel like you’re already in that part of your little library, so it shouldn’t be that much harder, but apparently, maybe it slightly is.

DANIEL: Apparently, it is.

BEN: I think potentially what it shows is that language is really hard and that our brains… As we’ve discussed a bunch of different times, our brain doesn’t do language in one little spot. That’s like this weird pop cultural belief that is really enduring but isn’t true. A huge portion of our brain activity is engaged for making language happen. And so, knowing more than one of those things probably does have a really substantial cognitive load. Even if you are in one of the libraries, like inside your little memory palace in your head, it still means that whatever land you have to devote to language libraries is probably somewhat limited. So, it’s not hugely surprising that there would be small but detectable differences for people who have to devote their land to more than one language library.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. Yeah, it’s true. Languages are expensive.

BEN: [CHUCKLES] Yes, exactly.

DANIEL: Which is why we ditch them as soon as we don’t keep using them. Let’s move to our last story. This one was suggested by Diego. In earlier episodes, we’ve talked about a really curious property of language called Zipf’s law. Remember Zipf’s law?

HEDVIG: Yep.

BEN: I, a) remember it and I, b) really enjoy you saying it.

DANIEL: Zipf’s Law.

BEN: Z-I-P-F.

DANIEL: I’m going to say it like Kermit the Frog. [KERMIT VOICE] Zipf’s law. What is it?

BEN: Zipf’s Law, if my memory serves me correctly, is the idea that every language will have a distribution of how commonly spoken or written certain words are. So, there is word number one, which is the most commonly spoken word in English. I believe it’s THE.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. That’s right.

BEN: Okay. And then, the Zipf’s law basically describes the property that all languages halve the incidence of the next word in the list. So, if the first and most common word is THE, and it’s like said 10% of all of the words that we say, the next one will be 5%, and the next one will be 2.5%, and the next one will be…

DANIEL: Not quite. Not quite. Let’s hone that a little bit. Hedvig, you got it?

HEDVIG: It’s not… The second one is half as common as the first one, roughly. And then, the other one is…

DANIEL: The third one is…

HEDVIG: …is the half of the second one or is the third of the first one?

DANIEL: It’s a third of the top.

HEDVIG: It’s the third one of the top. Yeah.

DANIEL: So, word number three is one-third as common as the top. Word number 10 is one-tenth as common as the word at the top…

BEN: Oh, okay, gotcha, gotcha.

DANIEL: …and so on. And in fact, we were asked once on a Mailbag episode if emoji show a Zipfian distribution and Hedvig, you found that they do.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah. I poked around. I made little plots and everything, so much fun.

DANIEL: Yeah, you totally did.

HEDVIG: I forgot all about that. That was so much fun. The funny thing about Zipf’s law is that it’s true for things that aren’t language as well. So, it supposedly kind of fits for population of cities.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: It’s like the most populous city in the world.

BEN: Oh, within a country… Yeah, okay.

HEDVIG: No, I think the world. I think also within countries. There’s a lot of things that show this kind of distribution. For language, sometimes people have a slightly modified one. I think that’s called the Mandelbrot Zipfian. Is that right, Daniel? Am I getting it right?

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. That’s right.

HEDVIG: Which is like there’s a bit of an adjustment, I think in the beginning and in the the first a couple of words and then is sort of Zipfian. But it’s like this weird pattern, like when you plot things, you’re like, “Huh, I keep seeing the same curve.”

BEN: So, in that regard, it’s not different from, say, the Fibonacci sequence. It describes things that exist in our world.

HEDVIG: Yes.

DANIEL: And sometimes, people massage the data to make it to justify a Zipfian or a Fibonacci distribution.

BEN: Right, right, right. That fifth value is nearly one-fifth! It’s close to one-fifth!

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Well, now it seems there’s something else that has a Zipfian distribution.

BEN: Ooh?

HEDVIG: Ooh.

DANIEL: The elements of whale song.

BEN: Well, I’m going to stop you there, Daniel, because I think we can all agree that this means that whales have language.

DANIEL: Oh, that’s a probably good take, isn’t it?

BEN: The good ‘ol…

DANIEL: Thank goodness I’m not seeing a lot of that in the press, but this is work from Dr Jeanne Allen of Griffith University and a team including Dr Inbal Arnon and Dr Simon Kirby, published in Science. The first thing they did was they took recordings of whale song collected over eight years and they identified what the little tiny pieces were. Now, how do you do that when you’re not a whale?

BEN: That’s a really good question.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Well, imagine this. Imagine words in English, all right? So, I say COFFEE, that’s /ka/ and /fi/. It’s very, very likely that /fi/ is going to come after ka. You know that because you know the transition probabilities, co-ffee, that’s not surprising. But after that, you kind of don’t know what’s coming next. Sometimes, the next thing is TABLE. Sometimes, the next thing is CUP. Sometimes, the next thing is POT. Sometimes, it’s something else entirely. Now, that uncertainty for what’s coming next tells you that COFFEE is a thing and that POT and CUP and TABLE are different units. Again, it’s surprisal.

HEDVIG: That’s true. But if we did that to like English, we’d get units that aren’t the things that we put spaces around in writing.

DANIEL: We get multiword expressions!

HEDVIG: We’ll get things that… English keeps being like, “Oh, I’m not a Germanic language. I’m like a Romance. I’m like something else.” So, that’s why you guys have all this problem with like datapoint, is it like a space in between, is it a dash or is there no space in between? Get. Your shit. Together. [LAUGHTER] And all the other Germanic languages are like, “Of course, it’s one word. We don’t put a space in between.”

DANIEL: That’s right.

HEDVIG: That’s the thing.

BEN: A good, sensible Deutsche system.

HEDVIG: Yeah. Dutch, Icelandic, we’re all like this. You’re the weird one.

DANIEL: Sort yourself out, English.

HEDVIG: Yeah. So, if you did that thing that they did to the whale song to English, you would get probably, I’ll guess you’ll get a Zipfian distribution of the frequencies, but I feel like it’s good to say you wouldn’t get what you get in writing probably.

DANIEL: Oh, good point.

BEN: Or at least it wouldn’t match up perfectly. There would be sometimes where you clump things and other times where you split things.

DANIEL: Well, now I want to know how things get clumped.

HEDVIG: And also in English, you know things about meaning. With the whale song, we have a bunch of sequences that we don’t necessarily know what they mean. So, you know that COFFEE and TOFFEE, that -FEE there doesn’t mean the same thing.

DANIEL: No.

HEDVIG: And therefore, you’re likely to say that they’re different. But this poor finding algorithm that’s looking through the whale song, probably, correct me if I’m wrong, but it didn’t know what anything meant right?

DANIEL: That’s correct. The author says, “Our study does not examine the meaning behind whale song sequences. We have no idea what these segments might mean to the whales, if they mean anything at all.” So, that’s a really good point. But my question is why would the elements have come down this way in their study?

BEN: I have an idea on that.

DANIEL: Okay, go ahead.

BEN: This is me being a bit cynical though, or maybe this is me being on the wrong bit of the Dunning-Kruger curve, where I think I know more than I do. But I’m seeing one possibility for a real data bleed, if that’s the right word. If you apply human language statistical analysis to whale song, and you say, “Hey, well, our language does this thing where we can guess probabilistically if things are associated together or separately based on the likelihood of them popping up or not.” Which is a property that exists in our language but doesn’t necessarily exist in whale language.

Now, we might be able to apply an algorithm and get a result, but we don’t know if that’s actually an accurate result. Like they said, “We don’t know what whales mean or intend.” Is there a possibility that because we have applied this probabilistic understanding to whale song that we have derived from human language, that we have created a Zipfian distribution because we have applied an algorithm from our language to the noises that they make?

DANIEL: Well, it’d be interesting to see what fails Zipfian tests, what doesn’t show a Zipfian distribution. I guess lots of things.

BEN: Yeah. That’s a good… If you do this to any animal noises and it all does this because you’re doing the same sort of probabilistic teasing apart of the noises that they make, I think that would suggest that all you’re doing is creating a Zipfian distribution arbitrarily out of the noises that they make, based on our own languages, systems and structures.

DANIEL: Interesting. Okay.

HEDVIG: I see what you’re saying, Ben. I don’t know how what we said about the have a unit, how likely is to be followed by another unit, some sort of mutual information thing, how that gives Zipfian, because it should be able to give anything.

DANIEL: It could be any distribution.

HEDVIG: What it sort of suggests is that in language, you have your THE and your ARE, and your like IS and stuff that are kind of semantically bleached, like they don’t have a lot of specific meaning, but they get used a lot. They do some sort of internal organising thing. And then, you have larger things that don’t get said as often, but that carry more specific information. And you have a sort of trade-off between being common and not being specific and being rare and being specific. And also, that seems to correlate probably with length somehow.

DANIEL: Yes, it does. That’s why MICROPHONE is long, but when we use MICROPHONE a lot, it becomes MIC, right?

HEDVIG: Right.

BEN: Right, right.

HEDVIG: Um, and just by the fact that you are rare, you’re probably more specific because you’re rare. So, what it tells me if whale song is Zipfian, is that maybe they also have those little, small helper units that are doing a little, “These two things belong together,” or, “Hey, I’m going to say a new thing,” or, “This is that,” or something like that. And then, they have things that are like, “And here’s the name of my mom. Can she come now?”

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Once again, we don’t know if that’s what they’re doing. The songs may be nothing more than, “This is me. This is me. This is me.” I was thinking as with language some things are easy to do and other things are hard to do, and we just do the easy things over and over again. And in language, we do efficient things over and over again because they take less effort. But this team thinks that whale song is culturally transmitted, which I think is reasonable because it’s different in different parts of the ocean. And culturally transmitted stuff just follows this pattern. Dr Allen says, “Cultural evolution inevitably leads to the emergence of properties that make learning easier. If a system’s hard to learn, it will not survive to the next generation of learners,” and Zipf’s law is just part of that.

BEN: Okay. That carries more sort of weight conceptually for me. That makes a bit more sense, right?

DANIEL: I think so.

BEN: When we are doing a thing where it needs to be absorbed somehow, so then you need to have an economy of absorption or it’s not going to work.

DANIEL: And once again, it doesn’t mean that whales got language any more than cities have language when their populations follow. A Zipfian distribution is just one more thing in nature that we see and it’s pretty cool.

BEN: But, Daniel?

DANIEL: Yes?

BEN: Perchance, is that the true language of god the Almighty being expressed in every facet of our lived experience in the cities, in the air and the trees? No, probably not.

DANIEL: According to their supplemental material, yes! So that’s cool. Oh, very neat. [BEN LAUGHS] Good job, Ben.

BEN: Just appendices to be: This is actually godspeak, expressed in all nature of living things. Anyway, byeeee!

DANIEL: So, well done for that team. Thanks, Diego, for that story. And now it’s time for Related or Not. Our theme this time comes from Gordon.

GORDAN: [SINGS THE RELATED OR NOT THEME] Hey, get ready. It’s time to start the game.

Which of these words come from words which were the same?

Do they share a common ancestor like the orange and the kumquat?

Though it might be there similarities amount to diddly squat.

Are they related or not?

Can you see how they’re connected? Can you trace the dots?

You don’t need to be a linguist or even a polyglot.

Are they related or not?

It doesn’t matter if they sound the same or if they’re close semantically.

The question is whether they exist on the same branch of the etymological tree.

Are they related or not? The aim of the game is in the name.

Are they related or not? Play it at home or on a train.

Are they related or not? Say it out louder in your brain.

Are they related or not?

HEDVIG: That’s so cute!

DANIEL: Yes. It’s one of my favorites.

HEDVIG: It’s so good. I like the diddly squat.

BEN: Yeah, the polyglot.

HEDVIG: I like the thing at the end.

DANIEL: That’s some shade there. You don’t have to be a linguist “or even a polyglot”.

HEDVIG: I like the “On a train.” I like the “Out loud in your brain.” I think it’s… Yeah, it’s very good.

DANIEL: It’s all good.

BEN: We’ve had heaps of submissions now, but I want to put a challenge out to the musically minded amongst our listeners. We’ve had quite a few sort of like Euro, poppy kind of dance-y kind of jobbies, and we’ve had quite a few sort of like fun folk numbers as well. I really want to hear some like…

HEDVIG: Punk?

BEN: …heavy, grimy. Yeah, punk would be good. I’m thinking like some Kyuss, some Tool inspired. Like, some really like, Djent kind of like [MAKES HEAVY METAL SOUNDS] blunkedy-dunk blunkedy-dunk. Like something like that. I want to hear some dirty intro.

DANIEL: Well, don’t forget we did have Tiago with Kargyraa throat singing.

HEDVIG: Exactly. I was just going to say that.

BEN: Which I enjoyed. Now, I want the musicality to back that up.

HEDVIG: You want it harder than that.

BEN: I want. Look, if you…

DANIEL: You want heavy.

BEN: …are playing a guitar and that guitar is tuned to drop D, you are heading in the right direction.

HEDVIG: That’s so funny that you want that because I was going to try and prod Ste to make something, but he’s probably going to make like a waltz, which is not what you want.

BEN: Which, 100% fine. Hey, if you’re listening and you have a thing you want to make, you fucking make that thing. Like, you go crazy. But if there is someone who’s listening who’s just like…

HEDVIG: But Ben won’t like it, yeah.

BEN: No, that’s not what I’m saying.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Ugh. Apparently, communicating requests is like the worst thing a person can do.

DANIEL: It is.

BEN: And I’m a scumbag, so, never mind.

DANIEL: It is hard.

HEDVIG: It is.

BEN: I will shut up.

DANIEL: Well, now let’s go to this first one from Coconut on our discord. I liked it, so I’m running with it. It’s the word BEAR.

HEDVIG: Oh, no. Okay. Yes. Okay.

DANIEL: To BEAR means to give birth or to BEAR means to endure, like, “I can’t bear children.” That’s both of those. To give birth, to endure. And then, BEAR, the animal, which of the three are related, if any?

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: And also, BARE feet?

DANIEL: Nope, that’s not in the game.

HEDVIG: Okay. Okay.

BEN: So, I want to make clear the semantic categories we’ve got going on here. And I think this is really helpful for people who listen because many of our listeners are not English as a first language people either, so it’s really helpful. And also, Hedvig, in that regard, you said BEAR as in to bear children, like as in bearing down during labor. Is that what you mean?

HEDVIG: No, it’s like, “I can’t BEAR children” could mean my body is not equipped to…

BEN: Bringing them into the world, gotcha.

HEDVIG: …carry them and bring them to fruition.

DANIEL: To BEAR children means to give birth. Yep.

BEN: Thing number two is like to BEAR arms, to hold.

DANIEL: No, “I can’t BEAR it.”

HEDVIG: This is funny. It’s like, “I don’t like it. I can’t stand it.”

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: I can’t stand it. I can’t bear it any longer, Ben.

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: And then BEAR the animal. Rawr. They’re all spelled the same. What do you think?

BEN: Are they? Okay.

HEDVIG: Yeah, they are.

DANIEL: Yes. That’s why I rejected bare feet. Get rid of it!

BEN: Oops. Okay. O. Kay. I have some ideas.

DANIEL: Well, why don’t we get started then?

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Okay.

HEDVIG: Okay. Ben, what do you think?

BEN: I think having kids and standing or enduring something are related. And I think “rawr” is different.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: I wholeheartedly agree because exactly of what Ben said about CARRY. I can’t hold it. I can’t… Yeah.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. So, it seems like giving birth and enduring really do seem like kind of the same thing.

BEN: My belief, my understanding is that I don’t think bearing children is so much the giving birth thing so much as it is…

HEDVIG: I don’t think so, being pregnant.

BEN: A pregnant woman is holding, is literally equipped to carry that child for gestation.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Which is not to say that bearing children is not an incredibly difficult task. Obviously, it is. So, in that sense, that’s where I think that similarity, because I said to BEAR arms, which is to carry, and you’re talking about standing or endure, like, “I can’t BEAR it anymore,” which is like, “I can’t keep carrying this thing…”

DANIEL: Can’t carry this any longer, yeah, yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Whereas BEAR, rawr, I think we’ve spoken about this before is a long sort of portmanteau of brown because it was like a forbidden word, and we didn’t use the word for the word because then we would invoke the spirit of the thing that kills you and eats you, so I think it’s different.

DANIEL: Okay. That is what I said as well, for the same reasons, and we are all correct.

BEN: Huzzah. [MAKES SHOOTING SOUNDS]

HEDVIG: Yah.

DANIEL: So, the two verbs are the same. And BEAR, the animal is not. Let’s go on to our second one. I was watching an episode of Tested with Adam Savage, the MythBusters guy, and he’s got his own podcast now called Tested, where he talks about making props. So, I started thinking about making PROPS in theater, giving somebody PROPS — Props to you for realising that — and then, does this have anything to do with PROPping up anything?

HEDVIG: Oh, god. Okay.

BEN: Oh. Now, this is a fun one. This is far less cut and dry than the first one, I reckon.

DANIEL: So, theater PROPS, giving someone PROPS, and PROPping something up.

BEN: Mm, I’m going to let Hedvig jump in first on this one because I bogarted on the last one.

HEDVIG: It’s hard because PROP, it strikes me as like the first part of a longer word, like proprietary or something, properly.

DANIEL: That’s got PRO- in there as well…

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: …which could, you know, PRO- in front of anything P turns into PROP. Like PROPELLER?

HEDVIG: Yeah, right. So, sounds like it’s a first part of a longer thing. Okay, so we have a PROP, that’s like on the stage, like, “Oh, this isn’t the real telephone. It’s a prop telephone.” Okay, so are they being prop… Or is the stage being propped up with the props? If by adding props, is that making the stage more believable, more good?

BEN: And that semantically shifted into holding things up?

HEDVIG: Yes. So, in giving props, is that like giving support, but giving props is like giving credit, right?

BEN: Yeah. Or even more like congratulations kind of thing. Like, well done, good job.

HEDVIG: Oh, god. Daniel, what have you given? What is this?

BEN: I’m going to make some guesses while Hedvig has a minor meltdown. I think that PROP, as in the word that we use for an item on stage, distinct from costumes and that sort of stuff…

DANIEL: Theatre PROP. Yep.

BEN: …is potentially quite an old word. I think we could probably anticipate that… because theatre is a fairly old tradition now, we’re talking like 400 years or 500 years, where some of that lingo might have been used fairly consistently and probably has a good chance of being like weird fossil words because that’s how people in those sorts of spaces tend to be. “We’re going to keep using the antiquated word because it’s cute and it makes us different.” I think that to give someone props is really modern and it’s going to be a contraction of something that I can’t guess. Like, it’s going to be like, “Oh, it’s actually a contraction of like PROPAGATE,” or something like that.

HEDVIG: Yeah, see, that’s a problem.

BEN: And I think to prop something up could potentially somehow be related to prop thing on a stage, but is not related to… Oh, actually, no, flip that. I reckon giving someone PROPS and to PROP something up are related somehow. And I think PROP on a stage is its own thing from a different avenue.

DANIEL: Okay. Theater prop is the odd one out for Ben.

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: Hedvig?

HEDVIG: I think they’re all related. And I want to put it to the… I think we’re also going to probably get into this like half-related because, like it’s going to be like that the PRO- is the same, but like something about the words and it’s going to be a mess.

DANIEL: How about if I tell you that the answer does not depend on PRO- being its own unit?

BEN: Oh, there we go. So, that puts that there.

HEDVIG: But PROP, do they all come from different words that start with prop? So, one comes from proprietary and one comes from propagate.

DANIEL: Oh, that would be different.

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Okay.

BEN: That’s not the same. Yeah.

HEDVIG: Okay. Anyway, I think they’re all related.

DANIEL: I said that too. I thought they were all related. Now, I know a few things about this that I was able to remember.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: First of all, a PROP in theater is called that because it is among the properties…

BEN: Oh.

DANIEL: …that the show has.

BEN: Gotcha.

DANIEL: Now…

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: …giving somebody PROPS is actually short for “giving somebody their propers”, their proper credit. So, if you know the song Respect by Aretha Franklin, [SINGING] give me my propers when you get home.

BEN: Okay. Give me my proper, gotcha.

HEDVIG: Yes, easy.

DANIEL: So that shortening to props is like…

HEDVIG: Wow.

DANIEL: When did that song come out? Actually, it was the number one hit the week I was born in 1967, so that’s pretty cool. It was either that or Groovin’ by the Rascals, but those are both great.

BEN: What’s this last one going to be, Daniel?

DANIEL: Hang on, I haven’t even said any answers yet. So, the correct answer is…

BEN: What? Yes, you have. The first two are related.

DANIEL: No, no, no. Hang on, because there’s something you don’t know. You see PROPERTY that is a theater PROP and PROPER from giving PROPS both go back to the same Latin word, which is proprios, something that one has, something that belongs to oneself. So, those two are related. However, Hedvig, we were both incorrect because PROPPING up, not related at all. Probably from Middle Dutch, proppe, which means a vine prop or a support or a stop for a bottle. So, that’s the one that wasn’t related at all.

BEN: Ah, I had the wrong one. I thought it was going to be… Argh.

HEDVIG: We call a stop for a bottle PROP as well.

DANIEL: Do you really? Well, it’s got a lot of Germanic reflexes. Yup, that’s right.

HEDVIG: I didn’t even think of that. I never thought of that.

DANIEL: There you go. Oh, man. You need to delve into your Scandi roots for this game, I think.

BEN: Apparently.

DANIEL: Let’s stop there. Thanks to Coconut and thanks once again to Gordon. If you’d like to donate, to gift us a theme song, a jingle for Related or Not, please do. That’s hello@becauselanguage.com, we’d love to hear from you.

[MUSIC]

[INTERVIEW BEGINS]

DANIEL: I’m talking with Michael Erard, linguist and author of the new book Bye Bye I Love You. Hi, Michael, thanks for coming on the show.

MICHAEL: Hey, Daniel, thanks for having me.

DANIEL: Bye Bye I Love You. That’s a good title because both of those things — bye bye and I love you — those are things you could say at the beginning of your life, at the end of your life, or anywhere in between. And titles are hard, so that’s a good one.

MICHAEL: Titles were hard and titles on this one were particularly hard because I didn’t want to privilege words. I didn’t want to privilege talking, and I wanted to capture some of the essence of the phenomena that I was talking about at both ends without kind of priming people too much in one direction and kind of undermining the argument as a whole. And of all of the options, we opted for… my editor, Phil Laughlin, and I opted for something that was sort of verified first word and something that was a verified last word or utterance, first utterance, late utterance, and put those together. And I think there’s a nice kind of tension or friction between the two.

DANIEL: I think so too. Although you mentioned not wanting to privilege words, and that’s really tough because at least as far as my culture, words are kind of the thing. Words are the things you notice. So, if there’s not words, what else are we talking about?

MICHAEL: When I first started the project, I was coming in with just, I think, the standard terminology or the usual nomenclature for these things, and words were it, and at least certainly on the early side, that there’s a threshold, there’s a milestone, and the way that we talk about that is we label it with words. And at the end of life, similarly, there’s the threshold, there’s the thing that you tell stories about, there’s the thing that you anthologize, and that was always famous last words.

What became clear though almost immediately was talking to people about end-of-life experiences that they’d had in communicating with a dying loved one was that there was so much other stuff going on, there were so many other behaviors that became meaningful that people told stories about that were not at all about the spoken or the signed lexical item, but some other sort of behavior. So immediately, that category of things blew up and I realized that I needed to be able to account for much more their many more phenomena. And in that, there were quite a few opportunities, I think, for thinking about what was going on.

For instance, if you are committed to a threshold, if you’re looking for some sort of thing that you can clearly use to demarcate a before and an after in developmental terms, then perhaps pointing is the thing that you should be looking for if you’re one of these people who’s going to be obsessively tracking what it is that a child is doing, that the point, the emergence of the point might be sort of a more clearly demarcated and discrete sort of thing than the utterance. But then, of course, like everything else, once you start to get into that, you say, “Well, do young children point with the index finger? Do they point with their whole hands? When does the index finger…?” So, once you direct, I think some empirical attention to that, then even that as a threshold might start to fall apart and I expect that a lot of people would come back to me and say, “Well, no, developmentally, actually, it is also very fuzzy.” Certainly, in evolutionary terms, it’s very fuzzy. So, the question of, do non-human apes point? Do they gesture in the wild? Do they point in the wild? If so, how do they point? Is a whole other set of questions and probably a whole other book.

DANIEL: Okay, so now that you’re mentioning pointing, I will just point out that you mention in the book that you did some time at the MPI, the Max Planck Institute, where you were hanging out with people who were studying way beyond language, looking at the level of the sign. And pointing is a very interesting sort of sign, because then what you’re doing is you’re trying to direct somebody else’s attentional focus to a thing, which is very much what I’ve done with my children. We’re looing at a thing together, or they’ll say, “Dad, look at this,” or we’ll be studying the same book or looking at the same video or something. So that is something very language-y and something very human as well.

MICHAEL: Yeah. And then, at the end of life, I think one of the opportunities that gets opened up when you pay attention to stuff that’s not just the word, is that it opens up the possibility of looking at communication function change over the trajectory of the end of life. And then, what emerges is a whole other set of questions about how you take advantage of the communication function that persists at particular times. So, not only how do things change, but how do things change relative to underlying medical conditions, and how do they change relative to who the communication partner is.

And that’s one thing that in the stories about last words canonically told, and even first words canonically told sort of erases or sort of omits that. It treats them like these broadcast utterances or these kind of monologic kinds of things, rather than something that happens over the course of an interaction that is about physical presence and the orientation of bodies and people’s eye gaze and then the way that they are sharing attention, trying to get something done and so forth. And so, what I wanted to try to do with the book is to return our awareness back to all of that interactive stuff and maybe return that to the stories that we want to tell about those things. I think once you sort of realize that we are telling stories about these things and that the stories are ours to tell, that there are opportunities for healing and connectedness that can happen when people sort of take control of their agency as storytellers.

DANIEL: Okay, so it sounds like we’re not talking so much about first and last words anymore, but first and last interactions. And to me, this feels much more normal and right. Even from a linguist, even as focused as I am on words, I think interactions is really where it happens.

MICHAEL: And that was the thing that I realized at the MPI, where I really encountered the interaction of linguistics for the first time. Maybe it had been around in some sort of way when I was in graduate school, but then I got directed away from that, but it was only at the MPI that I really not only encountered that, but kind of was stewing in that through presentations and conversations and things like that, and seeing, “Oh, right. I mean, one of the immediate implications of that too is that the last word is not the end of language, that’s not the end of interaction.”

I ended up borrowing a concept from a palliative care physician named Kathryn Mannix, who is a British doctor who does a lot of work around sort of advocacy for ordinary dying, and she writes really beautifully about end-of-life issues. But she has this notion of a conversation window, and I think what she was using that for was talking about that period of time before someone dies when you are able to have a meaningful conversation with them and say a meaningful goodbye and have a meaningful connection.

I broadened that out and said, well, because it’s not just a conversation that people have, it’s an interaction. And if you think of the interaction window at the end of life, then you would be looking at a larger set of phenomena that certainly come up in the stories that people tell about their deathbed experiences. And once you have interaction window, and I guess you have to be writing a book about first words and last words to see this, but you realize, “Oh, the interaction window works.” It’s an operative concept at the beginning of language and at the beginning of life as well. And so, it’s then worthwhile to talk about how people approach the interaction window at both ends and what is it that they do with it and how the structuring of that window maybe similar, different, obviously, but how is it similar in similar cultures and in similar historical periods at both ends of human life?

DANIEL: Let’s talk about culture for a second because you say in the book, “It’s so easy to get twisted up in your own cultural models.” And I thought that was a really interesting sentence. And so, it sounds like what we’re talking about here is that our culture allows us to see certain things, but it obscures other things from us. And so, when we’re hunting down first and last words, that’s a notion and it may not be the best way to do it. And it’s not the method that you use in the book. And what you’ve done with the interaction window and looking at events and interactions is more appropriate.

MICHAEL: You think so?

DANIEL: I think so.

MICHAEL: Yeah, no, I mean, that notion of getting twisted up in in your cultural models, we come to our caregiving activities and we come to our dying as socialized actors. We are enculturated bodies and embodied selves. And I think people, particularly with end-of-life people want to go… Well, like, what do people say at the end of their lives? As if there’s something natural that you say. But there’s nothing natural, it’s socialized.

DANIEL: I was having a bit of a joke with Ben and Hedvig at the top of the show. I said I’m planning my last words. Because that’s how it works, right? Here’s how I imagine it, okay. This is how it’s going to go down. I’m going to think of something really good, and then there’s going to be a time when I’m dying and everyone’s kind of around, and then I’ll say the thing and then die. And then, everybody will clap. And then as they leave, they’ll be like, “That was really good.” [LAUGHTER] But it’s not going to work that way. I mean, you’ve got to nail the timing, first of all, right?

MICHAEL: First of all. Yeah, yeah, yeah. One of the things that emerges when you look at religious traditions that give people specific things to say, what’s important in those traditions, one, is the thing that you’re saying, you’ve said it your whole life in a variety of contexts. So, you were so primed, it has such a privileged place, psycholinguistically, that is easy to produce. I mean, relatively easier to produce. So, there’s no performance anxiety around it. And those traditions also have these interesting kind of adaptation to the physiological realities of dying in order to make it easier for people to catch it, to catch the moment of death with a specific utterance.

Like chanting, for instance. There are Buddhist traditions where you’re supposed to chant and say a specific sound. And it’s not that you wait for the moment and then you burst out with the sound. It’s that you say the sound over and over again, which increases the likelihood that the two things will coincide. So, that’s what I mean by…

That gets back to that other thing about getting twisted up in cultural models. I interviewed this guy who had collected an anthology of “famous last words” and worked on it with his mother. He was steeped in the cultural model of dying, which is that the people retain their linguistic powers all the way to the end, and then they die, and they stop midsentence or midstream somehow. But then, he said, “Even though, like, my mother and I, we’d never talked about what our last words would be, and she didn’t have any actually when she passed away, it was more of a slowly fading dialogue.” And I thought that story from him… And he was a little bit saddened by that, I think. But it also, I think, revealed to him something about the reality that the famous last words was kind of standing against as maybe a comforting fantasy, maybe more than an obscuring one, say.

DANIEL: Yeah, but it sounded like it got in the way of… Like, it placed a series of really heavy expectations on them so that they felt like it had to be a certain way, like…

MICHAEL: Sure.

DANIEL: Whereas a more appropriate thing would be, let it happen, I guess. I don’t know what the rules are for this thing. But now let’s go back to words for a second, because I come…

MICHAEL: Sure, sure.

DANIEL: I come from a culture where words are valued. I’m a linguist dad with my children. I kept lists of words…

MICHAEL: Sure.

DANIEL: …that they were saying, but I kept this list of times and dates and what I thought was going on. That was a cultural notion. That grew out of a set of ideas that I had about what was important about language. And one thing that I got from the book was, yeah, maybe not. Maybe that’s not where it’s at. But what can you surmise about my culture from the idea that here I am, trying to make these lists of words and they have to be words?

MICHAEL: Yeah. I was like, “I see you, man. Like, I see. I see you.” Sorry, but…

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Yeah.

MICHAEL: And that’s another strange thing about having written this book. It’s kind of like I know more about people’s own last words or more about the language at the end of their lives than they ever will, which is kind of profound.

DANIEL: Yeah.

MICHAEL: But I think in that list, it was interesting because it had that very contemporary commitment to the notion that this is like a phase or that there’s no single thing, no single utterance that marks this threshold. That it’s really like a fuzzy kind of group of things that kind of characterizes that phase.

DANIEL: Mm. The words came slowly at first and stayed for a long time. Sometimes, they would disappear for a long time and then come back. And then, there was a time when I was… Like, I hadn’t believed that children could acquire 10 words a day, but when I really was having to keep that file open and keep adding the words, I realised, yep, it was about 10 words every single day for quite a while.

MICHAEL: Yeah, right. Yeah. And you were focusing on production. You weren’t tracking… Were you tracking things that she understood?

DANIEL: I tried but, of course, those things aren’t obvious, are they? There’s a bit of bias there, like novelty bias.

MICHAEL: Yeah, no, certainly. I mean, and I would admit to this too. I have lists of words, but they’re all lists that my kids produced, not lists of things that they comprehended. Because there’s something about speaking that’s more indicative of personhood, of agency, of participation, of socialness, than the comprehension. Even though in the language acquisition research, paying attention to both, and maybe even paying attention more to the comprehension side is important because you want to understand what’s the lag between the passive comprehension and the more active production, and are there differences there across categories. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah. I’m really interested in the idea that we see producing language as tied to a notion of personhood because if I’m on the farm and a chicken starts talking to me, I’m like, “Oh, crap, that chicken is a person.” In some cultures, they don’t even talk to children until they start talking themselves, because then you’ll be worth talking to, as you mentioned in the book.

MICHAEL: Yeah.

DANIEL: And I liked your metaphor of the house. I know that you worked on metaphor before, and I really love the notion that, here we are, we have a house of language, and when we hear first words, it’s a house that’s rapidly being built. And then, when we get to last words, it’s a house that’s coming down.

MICHAEL: Yeah. I devised that metaphor particularly for end of life because I felt like there needed to be some sort of way to talk about how it is that you can interact with people in certain states in ways that makes it seem like you’re talking to someone with an intact language system, but still sort of reserve space for suggesting that language system is actually kind of coming down in ways that aren’t immediately apparent. And I think that’s also true with early language as well. You put up something that kind of serves as a door or that serves as the interaction window, and you can use it that way, but it’s not connected to other stuff. It’s not connected to other parts of linguistic structure or to other ways of using language or certainly to a larger vocabulary. So, there is something there. It’s real, you can use it. And yet, it’s not a mature… It’s an impaired system.

And I mean, it’s interesting to think about even normally developing children as impaired if we didn’t have this kind of developmental overlay on it. If you forgot somehow that you had that expectation about what kids would do, and if you weren’t seeing change over time, any single interaction with a child, you’d be totally stumped about… It would seem like you were talking with… I mean, it’s an impairment. It’s communication… it’s a linguistic impairment. And, obviously, sometimes, most of the time at the end of life.

DANIEL: I’ve been thinking a lot about words, but I’ve also been thinking a lot about intention because that’s where the words kind of come out of. You mentioned how I was collecting words, but I wasn’t really sort of… I think one thing that was missing from my analysis was the intentionality. And I wanted to ask you a little bit about what you think about how we know what somebody intends. And I’m not just thinking about babies and older people. I’m thinking about, how do we know what each other intends in this interview? Or if we’re having breakfast or something.

MICHAEL: Sure. Or, machines or animals or things like that. I mean, there’s a word for that kind of bias, where you kind of impute. There’s an agency bias or something where you impute intentionality to things that have a certain kind of lifelike quality or fluency or something like that. And I think that is… We bring that to bear, but how do you prove it? How do you prove that it’s there? And I don’t know, that starts to get into philosophical arguments where that feel like sand dunes to me. I’m interested in this space where someone has to make a determination about the intentionality of something in a way that has consequences than for their ability to do other things.

And so, one of the questions that motivates the book is trying to resolve the fuzziness around, is this behavior, is this utterance, is this sort of seemingly communicative or linguistic behavior, is it coming from the self or is it coming from the organism? Because I would behave quite differently depending on how those two things resolve.

I’ve heard a story from someone recently who had to be present with a family member at the end of their life. And they were intubated, so couldn’t speak. And the only thing that they had was a sort of grasping gesture in the direction of the respirator or the oxygen tank or something like that. And so, it was this person’s job to interpret that as a deliberate, intentional message to say, “Turn the machine off.” Like, “I don’t want to be kept alive any longer.” And in that instance, what they described bringing to bear were previous conversations where the person had described their wishes. And so, even though that specific gesture in and of itself was not determined to be intentional, they were able to interpret that as connected to a set of previous, clearly intentional messages that they then acted upon in a particular way.

I mean, one of the things that you and I in this situation have available to us is that we can revisit and repair and clarify, “Is that what you meant to say?” Or to go back, one of the things that characterizes conversations beginning at end of life, but also with animals, and some kinds of machines, is that kind of meta discursive querying is not available, so it kind of remains inaccessible.

DANIEL: Okay, so we’re talking about words, we’re talking about interaction, we’re talking about intention, we’re talking about gesture, and we’re talking about what we know about each other. So, did you get the feeling that the scope of this project was really rapidly getting beyond words into big stuff?

MICHAEL: Oh, I mean, yeah, I was really aware of that the whole time. And the further I get away from it, the more aware I get, because it really is about everything, in a way. And I’m still reading things that I just want to take the book back and put this other stuff in there or reorient. There’s probably going to be… There will definitely be other things that I do from this. And at the beginning of the session, you were talking about, am I a journalist? What should I be called, right?

DANIEL: Right, Yeah, I was like, “Do I call you a journalist or an author? What do I call you?”

MICHAEL: Yeah, some of the things that I want to explore, really, I think work mostly in a scholarly key, so writing articles and submitting to journals and trying to bring things back to the fields that were the homelands for some of these concepts and say, well, when you talk about end of life, particularly this thing sort of shifts a little bit, you realize. So, that’s the direction that I’m heading.

DANIEL: Okay, well, now I’m really curious. So, what’s something that you’ve sort of discovered that makes you want to go, “Oh, no, I neglected this whole area.” Is there anything that you’ve noticed that makes you want to take the book back?

MICHAEL: Well, yeah, so there’s a notion of… And this comes from a scholar named Jacqueline Stone, who wrote about Medieval Japanese Buddhist ritual, last words. And she has this notion of moral physiology, which is the term that she uses to kind of characterize this whole set of approaches to these ritual utterances at end of life. How a dying person behaves and also how their corpse looks is indicative of their moral virtue.

DANIEL: No pressure.

MICHAEL: Right. Yeah, no pressure. And also, indicative of kind of what will happen to their soul in the afterlife. So, people who are calm and peaceful as they die, that’s the virtuous state. And people who are agitated or delirious or something like that, that’s the undesired state. And I realized that there’s a moral physiology that kind of underpins all of the last word traditions in a way whether you are given something scripted or whether you’re supposed to say something that marks you as an individual, because you can really only do that, you can really only produce those things with a certain level of composure or a certain level of functioning still. And that there is a moral quality that is attached to being able to do that. So, there’s a kind of moral linguistics, I think, that underpins the moral physiology and that’s something that I’ve only come to be talking about after the book is out.

Although certainly the book has a lot of elements of trying to, I think, free people from the obligation to either hear something or see something or to produce a particular thing, however, we want to talk about however we feel about the medicalization of death and dying in general, I think one legitimately positive contribution is the ability to say, “Look, that thing that’s happening, it’s entirely normal.” That someone is agitated and delirious, that’s normal. Just like this calm, peaceful thing, that’s also normal. And that there are no sort of moral implications that you should take away from any of this because it is all part of what happens as part of that experience.

DANIEL: That really came through in the book, and I thought that was really lovely. And I guess I was being a little bit hard on myself for wanting to plan my last words. But now, I think that what you’ve just said has helped me realise that desire is also very normal. I want to present well, even at that extremity.

MICHAEL: Sure.

DANIEL: And I don’t want the last thing that people take away from me to be like something stupid or something that doesn’t reflect who I feel like I want to be when I’m at that point. So, I guess I’m going to be a little bit easier on myself, because what you’re describing is really human.