Minority languages are under threat everywhere, but Tibet represents a particularly difficult challenge. The Tibetan language family is under pressure from (no surprise) Mandarin, even as community support for Tibetan remains high. But where does that leave the many other minority languages of the area, like Manegacha? Language policy, community pressure, and individual language choice are coming together in a turbulent mix. Is there any place for hope in this setting? Dr Gerald Roche tells us about this unique situation, drawing from his new book The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet.

Daniel chats with Dr Sasha Wilmoth about a very surprising sentence, and how our brains process language in some surprising ways.

Timestamps

Cold open: 0:00

Intros: 0:55

News: 5:30

Chat with Sasha Wilmoth: 21:30

Related or Not: 39:40

Interview with Gerald Roche: 54:40

Words of the Week: 2:02:56

The Reads: 2:29:16

Outtakes: 2:32:56

Listen to this episode

Video

Patreon supporters

Thanks to all our patrons! Shoutout to our patrons at the Supporter level.

This time we are ordering our Supporters alphabetically.

And then giving them a number, the order that they come in, in that list.

And then we are spelling that number out.

And then alphabetising that.

- Ariaflame

- Elías

- Canny Archer

- Colleen

- Rhian

- Tony

- Steele

- Stan

- Rodger

- Termy

- Tadhg

- Sonic Snejhog

- sæ̃m

- Amy

- Meredith

- Raina

- O Tim

- Nikoli

- Rene

- Whitney

- Molly Dee

- Rach

- PharaohKatt

- Nigel

- Nasrin

- Amir

- Chris W

- Ayesha

- Felicity

- aengryballs

- Andy from Logophilius

- Diego

- Andy

- Daniel

- WolfDog

- Ben

- Chris L

- Keith

- Margareth

- Luis

- LordMortis

- Matt

- Kevin

- Manú

- Lyssa

- Larry

- Kristofer

- Alyssa

- Cheyenne

- gramaryen

- Kate

- Jack

- J0HNTR0Y

- Kathy

- Joanna

- Ignacio

- Helen

- Aldo

And our newest patrons:

- At the Listener level: Jennifer A, Jennifer B, Vitor, MarkGammie, Rayley, Jason, and Matt S

- And our newest free members: Kate, Rachel, Convenientmarkertodreams, and Garnelenbox

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

Mary Walworth: Trickledown endangerment: The role of Tahitian in French Polynesia

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311767237_Trickledown_endangerment_The_role_of_Tahitian_in_French_Polynesia

Vowel signatures in emotional interjections and nonlinguistic vocalizations expressing pain, disgust, and joy across languages

https://pubs.aip.org/asa/jasa/article/156/5/3118/3319867/Vowel-signatures-in-emotional-interjections-and

I'm excited to share our new study on cross-modal iconicity from our special issue in JASA! We show [r] is rough and [l] is smooth even in languages that conflate them within one phoneme. The effect is even stronger than the bouba/kiki effect!

— Aleksandra Ćwiek (@acwiek.bsky.social) November 20, 2024 at 10:52 PM

The alveolar trill is perceived as jagged/rough by speakers of different languages

https://pubs.aip.org/asa/jasa/article/156/5/3468/3321514/The-alveolar-trill-is-perceived-as-jagged-rough-by

Plato’s Cratylus | Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plato-cratylus/

Cratylus by Plato

http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/cratylus.html

Potatoes are better than human blood at making space concrete bricks, scientists say

Our brains often fail to notice key words that can change the whole meaning of a sentence

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/07/120716091921.htm

True Or False? How Our Brain Processes Negative Statements

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090211122147.htm

Sasha’s homepage

https://sashawilmoth.com

Descendants of the Latin word “coquina” (kitchen) in Europe and beyond [OC] | Reddit

https://www.reddit.com/r/MapPorn/comments/gjvew7/descendants_of_the_latin_word_coquina_kitchen_in/

The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet by Gerald Roche

https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9781501777783/the-politics-of-language-oppression-in-tibet/

The Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages

https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/35478

Donald Laycock | Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Laycock

The “Blue Water Rule” and the self-determination of nations

https://www.cwis.org/2017/10/the-blue-water-rule-and-the-selft-determination-of-nations/

Tibetans protest against language curbs in Chinese schools

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/oct/20/tibetans-protest-language-chinese-schools

Another Day in the Colony by Chelsea Watego

https://www.uqp.com.au/books/another-day-in-the-colony

Mariame Kaba: Hope is a discipline

https://towardfreedom.org/story/archives/activism/hope-is-a-discipline/

American Kakistocracy | The Atlantic

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2024/11/american-kakistocracy-donald-trump-berlusconi/680675/

anticipatory compliance

#WordOfTheWeek

unless anyone has a better name for this— Because Language (@becauselangpod.bsky.social) November 18, 2024 at 10:01 AM

What are the South Korean origins of the feminist 4B movement rising in the United States?

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-11-13/south-korean-origins-4b-movement-us-trump-election/104586252

Why is it called the “4B” movement? | Mashed Radish

https://mashedradish.com/2024/11/14/4b-movement-korean-origin/

S. Korea to cut number of teachers amid diminishing student numbers | Straits Times

https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/south-korea-to-cut-number-of-teachers-amid-diminishing-student-numbers

Appendix:Ancient Greek third declension | Wikipedia

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Ancient_Greek_third_declension

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

HEDVIG: Could we put all of our transcripts into TSD [Time Series Data] files? Like, downloadable TSD files that are formatted so you can see who’s saying what, and then I can run a little R script and find things out?

DANIEL: Cool.

BEN: Oh, that sounds really fun and embarrassing.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Who swears more? Daniel, Ben or Hedvig?

BEN: Ben. Definitely Ben.

HEDVIG: Who talks the most?

BEN: Ooh, Daniel.

HEDVIG: You can do all kinds of things.

BEN: Yeah. Who interrupts the most? That could be really fun.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah, that’s one of us two, hey.

DANIEL: Yeah, that wouldn’t work because I separate you guys out in the edit.

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE THEME]

DANIEL: Hello, and welcome to Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. My name’s Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. Let’s start with Ben Ainslie. Ben, I forgot to do an intro. So, this is your chance to say whatever you want to, to our audience.

BEN: Oh, okay. Why don’t I do my own intro? Ooh, and let’s make Hedvig do one as well and we have to junt. Okay, here’s the challenge, Hedvig. And I’m making it hard for both of us, so don’t feel like I’m singling you out. We have to say something that is actually useful as a podcast introduction and is not either of us just giving into our deep-seated need to be like self-deprecating. So, I’ll go first. He joined the show… Oh, see, I was about to do it straight out. [LAUGHS]. I was going to be like, “He joined the show over 12 years ago and we haven’t been able to get rid of him, he’s Ben Ainslie.” That doesn’t meet our requirements though.

DANIEL: I still like it.

BEN: He has steadfastly… Oh, here’s how I split the baby. “He has steadfastly remained relatively ignorant of linguistic topics, which is a great use to us so he can act as the audience in the trio. It’s Ben Ainslie.”

DANIEL: Mm. That’s pretty good. I’ve often thought that if I could remember everything that I’ve ever said, I’d be brilliant.

BEN: I feel like I would mostly just be guilt ridden or embarrassed, one of the two.

DANIEL: Mm, mm. And, Hedvig Skirgård, it’s time for your intro. Go ahead. What do you want to say?

HEDVIG: Oh, god. She has a PhD in linguistics, and that’s practical when you talk about language and linguistics. Even if she doesn’t know everything, she still has the membership card.

BEN: [LAUGHS] It’s Hedvig.

DANIEL: It’s Hedvig Skirgård

HEDVIG: It’s Hedvig Skirgård. Yeah.

DANIEL: Let’s talk about what’s coming up on the show.

BEN: Yeah, why don’t we.

DANIEL: We’re going to be talking to Dr Gerald Roche of La Trobe University. He’s written a new book, The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet.

BEN: Just a little bit of controversy in that region, in that topic.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s right. Speakers of minority languages in Tibet are switching to Tibetan and its endangering smaller languages, not to mention the threat that Tibetan itself is under. And so, global advocacy groups are having a really hard time facing this challenge. We’re going to be talking to Dr Roche about that.

BEN: That is very cool.

HEDVIG: This is similar to what Dr Mary Walworth calls “trickle down endangerment”. She describes it in French Polynesia where smaller languages in French Polynesia are switching to Tahitian and people in Tahiti are switching to French.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: Dang. Yeah. Okay. So, lots of churn. Lots of churn going on. We’re going to find out about that. Plus, we’re doing news words and Related or Not. But first, we’ve got some information for patrons. So, there’s a lot going on from now until the rest of the year. Our next episode is a Diego show. Our friend, Diego Diaz, is curating a show for us, bringing us news, bringing us words, bringing us Related or Not. It’s going to be fun.

BEN: He’s a pretty top guy.

HEDVIG: He makes good selections. Yeah.

DANIEL: If you’re in the Listener level, you’ll be able to hear that. Our episode after that is a live episode. It’s our Words of the Week of the Year episode. It’s live. We’re going to have some special guests. We’re inviting everybody into a big old Zoom room. We’re going to have a great time talking about all the words of the year and they’re going to be featured from you because you, dear listener, are going to vote for your favorites. Even now, you can head to our socials, that’s BlueSky, that’s the other places. And you’ll be able to find all of our Words of the Week from this year, and you can just like them, and that’s how you can vote for them, and we’ll compile all the votes and we’ll count them down. Do you remember last year’s?

BEN: Do I remember last year’s? Yes. Yes, I do.

DANIEL: We had Cory Doctorow talking to us. We had…

BEN: That’s right.

DANIEL: The word was ENSHITTIFICATION. It was fantastic. It was really fun.

HEDVIG: Yes.

BEN: Top-tier word. And has only sadly become more relevant as the year…

HEDVIG: Yes.

DANIEL: I’m afraid so. Maybe we can make it the word again. No, not twice in a row. But all patrons, including free patrons, are invited to that. Also, our mailout. If you are a paid patron, you’ll be getting…

BEN: If you’re in arrears, take a hike!

DANIEL: I can’t do it for the free ones because the postage is a killer. But if you are paid up, you’ll be getting a mailout with lots of stickers. So, make sure that your address is up to date with Patreon. If you’re not a patron, why not become one? There’s a lot going on at patreon.com/becauselangpod. Phew.

HEDVIG: Phew indeed.

BEN: Why don’t you tell me something interesting that’s going on in the world of linguistics, Daniel?

DANIEL: I will. Let me ask a question here. Have you ever thought about the way that we say ow? But OW is kind of a word, and in other languages, when they give a cry of pain, they don’t say OW, they say something else.

BEN: Oh, I think I kind of knew this, but also until you said it right then, I never really properly knew it.

HEDVIG: It’s sort of a bit like the animal sounds, except then we’re trying to sort of pick up a sound that they’re making. Whereas…

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: …when we’re doing interjections like OW, we’re trying to form what comes out of us into a word, if that makes sense.

DANIEL: Yeah. Yeah. Now, tell me, what do people say instead of OW in a language that you know pretty well?

BEN: For some reason, AYA is coming to my mind from some sort of a language.

DANIEL: Well, Spanish is AY.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: Okay. Well, there we go. Maybe that’s what it is.

HEDVIG: Swedish is AY as well.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: I think a lot of them have AH.

DANIEL: Some sort of AH sound? Mm-hmm, okay.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: That’s interesting, because you’d think that such a spontaneous exclamation would be like really spontaneous. Instead, we say OUCH, and other languages conventionalise it differently. So, it’s a little bit…

BEN: Interesting.

DANIEL: …like a cry of the heart, a cri de coeur.

BEN: What if… Can I put a theory forward? And maybe this is where the story is going, and if I’m stealing the lead, I apologise.

DANIEL: Not at all.

BEN: Hedvig said this is a bit like the animal sounds, like cock-a-doodle-doo vs. coco-rico-rico and all that kind of thing, right?

HEDVIG: Mm-hmm.

BEN: But then, Hedvig, you said, but we’re not really trying to mimic a sound, but maybe we are.

DANIEL: Ooh, like what?

BEN: And by that, I mean, I don’t say OW when I hurt myself.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: Ouch.

BEN: And I would put it to you that not many people do unless, I don’t know, maybe they see a kid hurt themselves and they go, “ooh, ow…”

HEDVIG: Ooh, right.

DANIEL: Ouch.

BEN: …or something like that right? When I properly hurt myself enough to actually make me make a sound, it’ll be like a relatively involuntary sound of some kind. If I stub my toe, it’s like [MAKES A PAINFUL SOUND] or something like that. Or if I cut myself, I’ll go or something [MAKES A GASPING SOUND] oo, something right? And so maybe these words are all an attempt to give a name to this constellation of pain sounds that humans make.

HEDVIG: Do you never say… You’ve never hurt yourself at a level lower than stubbing the toe and said OUCH when it happened?

BEN: Maybe I’m just a weirdo?

DANIEL: Let’s hurt him and find out. I’ll be right over.

BEN: Or maybe I do it, and I don’t realise… [LAUGHS] [PUNCHING ONOMATOPOEIA]

DANIEL: Take that, Ben! What do you say now, Ben? What do you say now?

BEN: Yeah, I just don’t think… I don’t think I do. No.

DANIEL: Okay…

HEDVIG: Because I do, but I also make funny sounds when I sneeze, but I do consciously have a few milliseconds of… And then, I decide to say the thing. And then afterwards, sometimes I think to myself, “Well, was that a cry of pain because you thought about saying the thing you said?” So, that can’t be very spontaneous, can it?

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Yeah. So, this is sort of what I’m…

HEDVIG: And then, I get myself into, like, pain imposter syndrome, and I’m like, “Did I hurt myself?” And it’s like very stupid.

BEN: The inner monologues of linguists are frightening places.

DANIEL: Let’s get away from pain and talk about disgust. If you see a disgusting thing, what’s the vocalisation you might make in English or another language?

BEN: I know what you want me to say, which is EWW.

HEDVIG: ECCH.

DANIEL: Okay. You can say whatever you want to say.

HEDVIG: Yeah, it’s a more closed vowel and back vowel. It’s aa, eww.

BEN: Eww.

DANIEL: Sorry. Open and closed? Can we go back a bit? So open would be…

HEDVIG: So, it’s like higher and further… Well, it could be back or front because EGH, UGH, I would do both.

BEN: I would go with UGH, like EWW.

DANIEL: AA, AA.]

HEDVIG: Yeah AA.

DANIEL: So, an open sound would be AA, and a slightly more closed sound would be egh or urr, or agh, maybe even ee, that’s really tight.

BEN: Like, you’ve got tight lips as you form the vowel, like eww.

DANIEL: How about a spontaneous cry of joy?

BEN: Daniel.

HEDVIG: He’s taking us on a tour through the vowel system because now he wants us to go high and back…

BEN: What I loved… What I particularly enjoyed is he just asked two Millennials, “What spontaneous noises of joy do you make?” And it’s like, dude…

DANIEL: Must be something, folks.

HEDVIG: Yay, woohoo.

BEN: …we’re in our mid to late 30s. That shit doesn’t happen very often.

DANIEL: Do you just say [SARCASTIC VOICE] WHOOPTY-DOOPTY?

HEDVIG: Well, I mean, if something good happens for someone else, I clap my hands.

BEN: I think I do like a “Heya” or something like that.

DANIEL: You know, we tend to think that we say WOOHOO, and that’s…

BEN: No one. Yeah, no, I’m not claiming that.

DANIEL: Woo hoo! I mean, when we perform a spontaneous joy thing, then we tend to say something like WOOHOO, but I feel like…

BEN: If we perform, is it spontaneous, Daniel? We’ve been through this.

DANIEL: I feel like that’s only a Simpsons thing. I feel like WOOHOO has only been since either Homer Simpson…

BEN: Yeah, yeah, I’d agree with that.

DANIEL: …or Blur, Song 2, which also, I think, ties back to Simpson, woohoo. I think YAHOO would have been earlier.

BEN: I agree. Yeah. In Australia now, it’s YEEEW.

DANIEL: Yeeew. We’re looking at nonverbal vocalisations. And at stake in this discussion is how far does iconicity go? That’s the onomatopoeia thing. How far does sound symbolism go? Is there any universality in this? Now, this research comes from Dr Maia Ponsonnet of the University of Western Australia — my colleague — and a team. Maia has been on the show before, episode 387 of Talk the Talk. This is Dr Ponsonnet and a team published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. I didn’t know it was Maia when I picked it out, but I like her work anyway.

HEDVIG: Oh, my god. Wait, she emailed me about this. I filled in her questionnaire. I know this.

DANIEL: Oh, so you’re data?

HEDVIG: Yeah, I submitted the data for Swedish. I had to, like, ask a bunch of Swedes also to make sure I wasn’t… a weirdo.

DANIEL: We’ve got a window into this research. This is great. Now, we have to cut you out for this part. For impartiality.

BEN: Yeah, you’re a data point.

DANIEL: Conflict of interest. Sorry, you’re gone. No. Tell us about what you did for this one. What was your data like? What did they have you do?

HEDVIG: I know Maia and she emailed me and said we’re collecting data from lots of languages and we want like anger, joy, disgust. Or sorry, pain, joy, disgust,

DANIEL: Pain, joy and disgust. Those three.

HEDVIG: And like, the words. And there were all these qualifiers about how the words should… Similar to basic colour terms, there are criteria and then write them down and then write an IPA transcription of it, so I did that. But yeah, it was hard for… I think especially for disgust, I didn’t have that many different ones, I think.

DANIEL: It’s hard to find words like actual words. Like, we’ve got one, we’ve got eww.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: Or ugh, U-G-H, I guess.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: The team did look at vocalisations, the actual words, and this is conventional for joy, pain, and disgust across up to 131 languages, across five different regions of the world, that’s Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and Latin America. But looking at words was just one part. In another part, they looked at nonverbal vocalisations in the situation. They got people to act out these things. Not necessarily looking at words you might find in a dictionary, but words that people might say.

BEN: But you said nonverbal.

DANIEL: Yes. So, for example, OUCH is a word, so that’s verbal. But if I say [PAIN ONOMATOPOEIA]…

BEN: Oh, okay, okay.

DANIEL: That’s vocal but not verbal. It’s not conventionalised. Yeah. Okay. Well, let’s get to the results. They found that for pain, the results were pretty uniform. A lot of people do some kind of open vowel, like ah, ahh, ow. Even ow is on ah sound. Disgust was more, as we found, kind of central. Like, wugh, wegh, that’s kind of a middle vowel, not an ah, it was an ah. It was usually something like eh. Joy was really different. If you look at the plots for joy, you’ll find that it’s all over the place. It’s spread across the /a/ area. But also, there’s a lot of /i/ going on, like WHEE, I guess.

HEDVIG: Yeah. I’m looking at my responses that I sent in to her, and that was pretty good. So, the joy ones I wrote, like, HOORAH, HEYA, TOPPEN, YIPPEE, and YES.

BEN: YIPPEE. Yeah, I love YIPPEE.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Hmm. And that’s conventional. Yeah.

HEDVIG: And it was hard. Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay, so that’s an interesting datapoint, and I just want to give one of my favorite facts. Do you know where OOPS comes from? Why do we say OOPS when we make a tiny little mistake?

BEN: This I do not know.

HEDVIG: Why do we say oops? I don’t know. But I do know that Germans say Uppsala, and I am from a city called Uppsala.

HEDVIG: Yeah, you are.

HEDVIG: It’s very confusing. Uppsala.

BEN: Is that because they… Is that like a Timbuktu thing where they’ve just been like, “Everyone from this city is really clumsy, so we’re going to use that word when…”?

HEDVIG: I don’t think so. I think it’s going to connect to the etymology that Daniel’s going to say.

DANIEL: Where are you from? Stumbleton.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Well, let’s just say that you see a child and they stack it, kaboof. And what you do is, in English, at least you pick them up, you say UPS A DAISY.

BEN: Upsy daisy. Yeah.

DANIEL: Or UP A DAISY or something like that. And UP A DAISY became UPS A DAISY, and then that became OOPS A DAISY, and it just got shortened to OOPS. So, it’s from picking a child up.

BEN: That’s really cute.

DANIEL: It’s related to UP.

BEN: Upsy daisy. Yeah. That’s so funny.

DANIEL: Although I got to say that OED says it’s possibly a natural cry, which is the last resort of a scoundrel.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay, let’s take a look at another one about sound, and this one is from a team. It’s Aleksandra Ćwiek of the Leibniz-Centre General Linguistics in Berlin and a team. Dan Dediu is on this one. We know Dan. He’s been on the show before. Published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America as well. Now, let’s see. We all know about the kiki and bouba effect.

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: The one where you give somebody a spiky shape and you give somebody a blobby shape. And everyone knows across languages that kiki is the spiky one and bouba is the blobby one. And that does not have anything to do with the way that the letters look in the language, it’s independent of that. I’m going to name some sounds, and you can tell me how you would draw these sounds on a piece of paper.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: How about the /t/ sound, as in T?

BEN: How I would draw it on a piece of paper…? Oh, like what shapey kind of thing?

DANIEL: Yeah, yeah. I give you a little card, and you are going to draw…

BEN: Probably like right angles. Something with like edges.

DANIEL: Oh, yeah. Okay. It’s got a bit of a corner to it. Would you agree?

HEDVIG: Ben, would you change your mind if I put the T in a word like tutu?

BEN: No, I would say that still is quite like a… Not as spiky as Kiki, but still, like, there’s edges, there’s cornices to this particular sound. It’s definitely not all curves.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: Okay, how about an /l/ sound? The letter L is usually…

HEDVIG: La-la, lu-lu, li-li.

DANIEL: Lemon.

BECCA: Thinking like a wavy line, maybe not necessarily a blob, but just like a sinuous kind of curve.

DANIEL: Okay, no wrong answers. No wrong answers. Now, I’m going to give another sound, the /r/, the rolled R. How would you draw that, Ben?

BEN: That’s got to be a really short zigzag, like a [MAKES SPIKY SOUNDS]

DANIEL: [CHUCKLES] Okay. Interesting. Now, it’s been noticed that words for roughness, like rough and abrasive, they use the R sound not just in English, but in lots of other languages. They’ll use some kind of /ɹ/ [NOTE: COMMON R IN ENGLISH] or /r/ [NOTE: TRILLED R] or something like that.

BEN: Interesting.

DANIEL: It’s not just the trill, the /r/. It’s other R’s as well. Well, this team got about a thousand people to participate from a wide range of languages, some from places that were kind of modern, some from places that didn’t even have electricity. They were trying to account for cultural bias. And they gave them two cards. One was a straight line, horizontal, and the other was a jaggy rickrack, the kind that you have described, Ben.

BEN: Ahhh!

DANIEL: And they would ask, they would give people the /r/ sound and ask them which one do you associate with that? And they found that people really do associate the /r/ sound with a jaggy line almost 90% of the time that’s stronger than the Kiki, bouba effect.

BEN: I want listeners to know this was not a setup. I was not given any of this information beforehand. That was just 100% me sort of exemplifying the data clearly.

DANIEL: It’s a strong effect, even Ben was able to come up with that.

BEN: Even knuckle-dragging simian, Ben Ainslie, was able to arrive at the right answer.

DANIEL: And the effect held for languages that don’t even have an R and L contrast.

BEN: Wow.

DANIEL: Which was interesting.

BEN: That’s super cool.

DANIEL: One weird result was that if your language has /r/ as the main… Like, there are languages that have a bunch of R sounds. There’s /ɾ/ in English and /ɹ/ in English, we don’t have a /r/ usually. But if your language just had the /r/ as the main R sound, then the effect was actually a little weaker.

BEN: I guess that kind of tracks though because if you’re using it so ubiquitously across all of your words with an R sound, then it would probably lose some of its intensity, maybe.

DANIEL: Possibly, possibly. I mean, things are noticeable because they contrast. And if you don’t have that contrast, then maybe the effect is weaker.

HEDVIG: How big of effect is there? And also, R is notoriously a sound that’s produced very differently in different contexts and in different languages. But this was like a proper alveolar trill that they got to hear every time, right?

DANIEL: Rruh, yep, that’s right.

HEDVIG: Yeah. Okay, cool. That sounds really cool. It reminded me of when I decided I was going to start studying linguistics, my dad gave me Plato’s dialogue, Cratylus. Do you know?

DANIEL: I remember the Cratylus dialogue. Yeah.

BEN: I am not familiar.

HEDVIG: Okay. Plato’s dialogues in general is that he takes Socrates and makes Socrates say what Plato believes is true to someone who’s a dumdum roughly.

BEN: Succinctly.

DANIEL: And I’m just asking questions, says Socrates.

HEDVIG: Yeah. Anyway, I think they talk about… I was just looking up like a translation because I couldn’t find it, but because they talk about R being associated with motion, I think.

DANIEL: Oh, interesting.

HEDVIG: And that like names… because they talk about the origins of names and how all names are like, tied to meaning and are depicting like all sounds are as well. So, if a name has an R sound, then it’s supposed to depict a noun, but I can’t find the exact quote.

DANIEL: They take it a bit far in the Cratylus dialogue.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

BEN: That does sound a little bit like two uncles at a party being like, “You ever thought about how sounds all came from somewhere?”

HEDVIG: I mean…

DANIEL: “Have you ever really looked at your hands?”

HEDVIG: I think it’s a good place to start.

DANIEL: Yeah, it’s really. I did an extended bit for my master’s thesis. Please don’t read my master’s thesis. There’s a lot of Cratylus in there though. But I think these two studies are a really interesting look at sound symbolism and how it ties into word creation. So, we’ll have links to those on the show notes for this episode.

HEDVIG: That is really cool.

DANIEL: Lastly, for our news, I noticed this really weird headline and I’d like to read it to you, you ready? This is from space.com. “Potatoes are better than human blood at making space concrete bricks, scientists say.”

HEDVIG: I love this headline. I like it so much. Yeah, I like it.

DANIEL: Why do you like it so much?

HEDVIG: Because it’s just really fun.

DANIEL: Do you like the thought of turning human blood into concrete space bricks and imagining what horrors exist?

BEN: Can I guess, Hedvig? Can I try and put words to what you about to try and say? This feels like white-hat clickbait.

DANIEL: Please explain that.

BEN: Like, it feels like playful, good-natured clickbait. Because obviously that title gives you no actual helpful information, but it definitely makes you want to find out what’s going on.

HEDVIG: They’re trying to make materials because say you want to build something on moon or mars and you have to transfer all the materials. So, they’re doing these things with like making bacteria excrete cement and stuff like that. Yeah.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah. That’s pretty cool.

HEDVIG: Yeah, it’s pretty cool.

BEN: I’m in the same boat. I like this headline because it’s like good-natured tomfoolery clickbait instead of like, “You won’t believe what this medical disaster looks like,” or whatever.

HEDVIG: Yeah, exactly.

BEN: “You won’t believe what they’re building space bricks out of now.”

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Well, the funny thing about that sentence though was that it took me a weirdly long time to process.

BEN: Really?

DANIEL: It did. I was looking at that and thinking, “human blood, concrete, space?” There was enough gaps in my knowledge that I had a really hard time figuring out. If you did a quiz for me afterward and said, “What’s better at making concrete space bricks? Potatoes or human blood?”, I would have to think about it. And then, I would say, “Uh, th-the potatoes?” but I wouldn’t be sure why.

BEN: Oh, man. Yeah, I did not…

HEDVIG: I’m worried for you.

BEN: I did not encounter any semantic ambiguity there at all.

DANIEL: I’m not saying there’s ambiguity, but for some reason I really had to think through that sentence because there was…

HEDVIG: I think that makes sense. If you don’t… maybe Ben and I just have a wilder imagination.

BEN: We’ve read more speculative fiction in our lives.

DANIEL: Yeah. You probably have to for sure. For sure. Yeah, that makes sense.

BEN: What I will say is this, actually, for me, fires off something that I’ve been kind of noticing for a long time now. And this doesn’t do it, but it reminds me of lots of things that do do it, which is a lot of newspaper subheadings employ grammar that I find deeply baffling. So, like what Daniel just described, but like way worse, where it’ll be like something, something, something, comma, something, something, something. And I’m just like, “Wait, how did the… What the fuck? How does this…?” And I’m like, I’m not dumb. I know, I’m not dumb. And I’m a reader, I read things. I’m not supposed to be bad.

HEDVIG: No, no, that’s true.

BEN: But I’m bad at this.

DANIEL: That was what I went through.

HEDVIG: No, it’s a thing. Oh, but usually something like, “Ministers said to have…” and it’s like these, like, weird this… Because this isn’t a weird grammar.

BEN: No.

HEDVIG: Potatoes are better than human blood of making space bricks.

DANIEL: X is better than Y at doing Z. Yeah.

BEN: Scientists say. The only thing that could be a little bit confusing there is like scientists say at the end, so you kind of go, “Oh, okay. It was a scientist who said it.” Anyway, sorry, Daniel, we’ve got really bogged down in the title. Was there story here we needed to talk about?

DANIEL: You must admit that it does make you pause and think about the situation that gave rise to this research.

BEN: Definitely, which is why it’s a good headline. Because I immediately was like, “They’re making space bricks out of both potatoes and human blood? Tell me more.”

DANIEL: And comparing the results?

HEDVIG: It sets up a very fun premise. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yes, sure. Well, I mentioned this on Twitter. I said, “This took me a long time.” And you know who got in touch? Dr Sasha Wilmoth, who I think is a friend of yours, Hedvig. Didn’t you know Sasha at ANU?

HEDVIG: Yes, yes, I messaged her. I actually messaged her about something else the other week, and then I saw that you had talked to her, and I was like, “Oh, my god, I can’t believe I missed Daniel… meh meh meh meh.”

DANIEL: Well, she was very helpful because she came in and said, “This is a really weird sentence and here’s exactly why.” And she gave me charts and graphs and a full explanation. I said, “Hey, come on the show and talk about this.”

BEN: Hey, anytime you want to validate my perspective on how things work, you’re welcome. So, tell us… Well, lay it on us then, Daniel, why is this a bit wackadoodle? Why did it take you a while?

DANIEL: Let’s find out from linguist Sasha Wilmoth, of the University of Melbourne.

[INTERVIEW BEGINS]

DANIEL: I wanted to ask you about a headline that took me a weirdly long time to process, but your background isn’t in processing. So, what do you do normally?

SASHA WILMOTH: I work in language documentation, particularly on Australian Aboriginal languages, and I’ve mostly worked on Pitjantjatjara, which is a language in Central Australia. And I have done some processing research with some psycholinguist colleagues, but it’s not my main area of research.

DANIEL: Ah, so that’s why you got in touch on this Twitter thread that I saw.

SASHA: Yeah, because I had that same experience of reading that sentence and it was so jarring. My brain was like: doot, doot, doot, doot. Like, every word just took a while. So, I was like, “What is going on here?”

DANIEL: That’s what I liked about this. And we’re going to get to the sentence. But I’m really interested in this because I love thinking about how language in some ways takes the form it does because of demands on processing. We try to make things easier on our listeners. And also, we’ve been talking with Dr Mark Ellison about attention. We don’t like to pay constant close attention to someone. So, we pay close-enough attention and meanwhile, we’re making tons of predictions about what’s going to happen so that if there’s a mismatch, we can go back and ask. We do a lot of shallow processing. Have I got that about right?

SASHA: Yeah, that’s exactly right. So, there’s the pressure on… We want to make it easier on our listener, but we also have this sometimes competing pressure to make it easy for ourselves. So, we want to expend as little effort as possible, but if we just say “buh” for everything, then that’s not going to be easy for our audience. But at the same time, if we make things super, super clear and explicit for our audience, that requires a lot of effort from us. So, there’s these two competing pressures.

DANIEL: It requires a lot of effort from us. But also getting things into words very precisely takes a lot of time. Like, Stephen Levinson says, encoding is slow, but decoding is fast, so our listener’s going to get bored. So, there’s that kind of pressure too.

SASHA: Yeah, exactly. And the thing about close attention that Mark was saying, although I haven’t listened to that conversation yet, [DANIEL CHUCKLES] there’s sort of this principle which people have called the Uniform Information Density principle. So, we want to keep the amount of information fairly constant and easy on our listener so we’re not packing too much into one sentence, which is what was so weird about that headline.

DANIEL: Okay, well, let’s get to the headline then. Would you read it out for me? It’s from space.com.

SASHA: Sure. So, it is, “Potatoes are better than human blood for making space concrete bricks, scientists say.” It’s hard to even read out.

DANIEL: I know, I’m tripping over it. And I also love how it’s a completely bonkers headline, but then it ends, comma, “scientists say”, in a completely normal fashion. So, why did this tie us up so badly, do you think?

SASHA: So, the reason is most of the words in this sentence, even though it’s like grammatically very normal sentence, the words are very unpredictable. So, it’s very uncommon to start with POTATOES.

DANIEL: It is? Okay. All right. It’s not very common. I haven’t done it for a while.

SASHA: Yeah, exactly but not unheard of. But if you start a word with POTATOES, then the chances of the second word being ARE is pretty high.

DANIEL: Pretty good.

SASHA: There could be some other things there, but pretty likely to be ARE. And then, BETTER THAN, that’s not too crazy. But then, it’s when we get to almost every single other word, they just are so unpredictable. We can’t anticipate what’s coming next.

DANIEL: Human blood.

SASHA: Yeah. I actually don’t even know what the story is about.

DANIEL: I don’t either, and I’m not able to guess.

SASHA: Yeah. I prefer not knowing, I think.

DANIEL: Yeah. I had so many questions, I got lost. I mean, what is a space brick? How do you make one out of a potato? And why would you? And then BLOOD? What?

SASHA: And then, why are you comparing potatoes and human blood? Like, that’s your two options?

DANIEL: So, we’ve talked about garden path sentences before where the syntax kind of messes you up. For example, “The prime number few.” What? The prime number… Oh, this wasn’t PRIME NUMBER. This was the prime. Those in their prime…

SASHA: Oh, okay. Yep.

DANIEL: …number few, right?

SASHA: Yep.

DANIEL: So, PRIME sounded like it was going to be an adjective, but it wasn’t. It was a noun, and everything went wrong there. But this isn’t a garden path sentence at all. It’s a straightforward sentence.

SASHA: It’s grammatically, syntactically, completely straightforward, yeah. So, it’s just the semantics and the unpredictable words that are tripping us up.

DANIEL: Okay, well, let’s talk about the surprisingness then, because in the… Do you have a favorite name for Twitter now?

SASHA: I call it Twitter.

DANIEL: Okay.

SASHA: I’m sticking with that.

DANIEL: I like… They can’t make us shift.

SASHA: Exactly.

DANIEL: I’ve had jerks say, “You’re deadnaming Twitter.” I was like, “Fuck off.” Anyway…

SASHA: Yeah. Twitter’s not a person. We can deadname it.

DANIEL: Exactly.

SASHA: That’s fine.

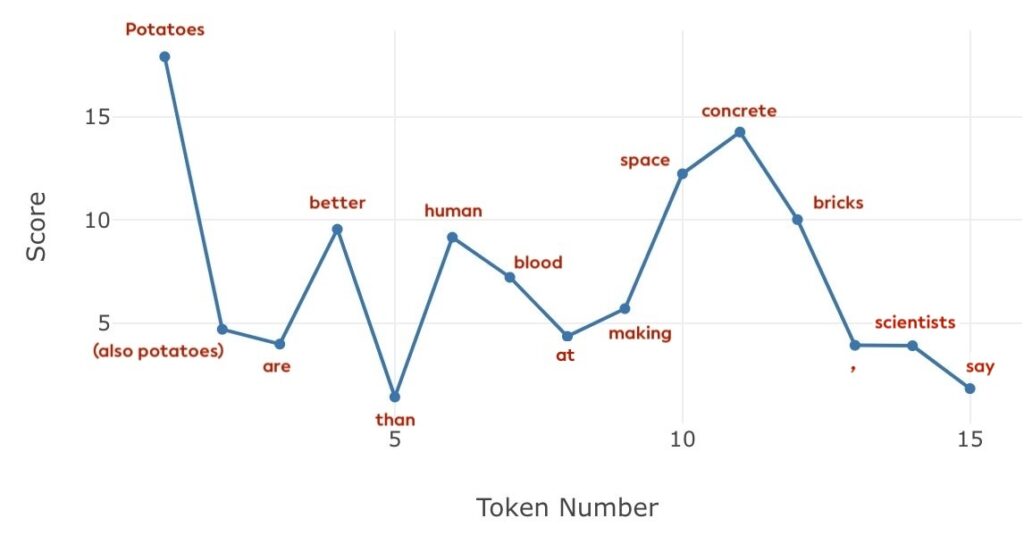

DANIEL: So, you showed a graph that has… I’m just looking at it now, and I’m going to slap this up on the show notes for this episode. But what I’m seeing here is a very bumpy graph. I guess if it’s up more, then it’s the surprisingness. And every stop on this bus trip that this graph is, is a word. Have I got that right?

SASHA: Yeah, exactly. Pretty much. So, this is a graph of surprisal, which is basically surprisingness. And you can quantify that using information theoretic techniques. So, this is like a whole field of mathematics and linguists can apply that to language as well. So, we can actually tell what are the chances of each word occurring. And then, if it’s a very uncommon one, that’s very surprising, we say that has more information content in that word.

DANIEL: Okay. So, we’re not measuring any kind of physiological response in me for this bumpy chart.

SASHA: No.

DANIEL: We’re looking at how likely a word is to occur at all, and then maybe also in context?

SASHA: Yeah. So, this is about how likely a word is to occur based on the word that came before it.

DANIEL: Okay.

SASHA: And so, this is based on corpus data. So, huge amounts of text in English. And then, language models can sort of quantify what are the chances of each word following another word.

DANIEL: Okay, so on the chart, it starts out really high. You said that it splits up POTATOES. It made POTATO the first token and the second token?

SASHA: Yeah, I’m not sure why that was. I think that’s just some weird quirk of the algorithm or the data that they’re using.

HEDVIG: Okay, so POTATO, as you say, was the most surprising word. It’s way up there on the chart, and that’s a weird way to start a sentence. Okay, that’s the surprisingness. Then, it goes way down for ARE BETTER THAN.

SASHA: Yep. So, you can see BETTER is the first little spike up. And then, THAN it goes way down, because THAN is almost redundant.

DANIEL: BETTER THAN.

SASHA: Well, not quite. Yeah, it’s…

DANIEL: I hear BETTER THAN all the time.

SASHA: Exactly. Yeah.

DANIEL: Then I get a slightly more surprising… Now, it goes up for HUMAN BLOOD.

SASHA: Yeah.

DANIEL: I guess HUMAN BLOOD is just very vivid. It’s something that you… you weren’t expecting that, especially in the context of potatoes.

SASHA: Yeah, exactly.

DANIEL: Okay. And then, FOR goes down again.

SASHA: Goes down and then up for MAKING, just not that surprising.

DANIEL: A little bit. A little bit.

SASHA: A little bit.

DANIEL: And then, SPACE CONCRETE BRICKS. There it goes.

SASHA: Yeah. So, that’s like three highly surprising words in a row. You cannot predict what’s coming next after each of those.

DANIEL: SCIENTISTS SAY. And then you see that SCIENTISTS SAY is way down again, because that’s a totally normal thing. And then the last one is the end.

SASHA: So actually, there’s the… I think the comma counts as its own token in the way that it’s…

DANIEL: Ah, comma is a token, naturally. Okay. Well, I think we’ve explained the surprisingness. It takes a lot of weird twists and turns, and that’s all in the semantics. You mentioned that this was an “entropic sentence”. What does that mean?

SASHA: Yes. Maybe it should have been a bit more precise and said that the sentence overall has a high information content or high surprisal overall, but I could say at each point, there’s a high conditional entropy. So, entropy sort of meaning uncertainty.

DANIEL: Okay.

SASHA: So, at each point, we sort of don’t know what’s coming next. And overall, it’s very surprising.

DANIEL: So, the more surprising it is, the higher the entropy, is that right?

SASHA: Yeah. So surprisal is a measure of the information in a single event, and entropy is a measure of the uncertainty across a distribution of events.

DANIEL: Is that like how easy it would be for me to replace a word if it went missing? Does that have anything to do with entropy? This is something I understand very poorly.

SASHA: What do you mean, if a word went missing?

DANIEL: If there was some noise, or a car horn went off and I couldn’t hear a word that you said, how likely would I be…? If somebody honked the horn at THAN in BETTER THAN. I could get that back. I could get that back. But if it was CONCRETE, I’d miss it. I wouldn’t… So, does that have anything to do with the entropy?

SASHA: Yeah, it absolutely does. That’s a great thing to maybe explain. So, this comes from a sort of model of communication that Claude Shannon came up with in the 1940s when he was working on cryptography during the war effort. And so, he was interested in how do you compress information as much as possible. And the model of communication is that you have some sender. I have a message. I have something I want to say to you. And I encode it into some signal. That could be speech. It could be morse code or smoke signals or anything, but some sort of signal where we’ve agreed on what the code is. And then, you, as the receiver, have to decode it and it crosses some… That signal might be through a noisy channel. So, there might be a car driving past or honking or something like that. And then, you have to be able to decode it and narrow down the message to my one intended message.

The reason that we have lots of redundancy in human language is sort of because we’re always in a noisy channel. There might be something else interfering with the message as well as the processing cost. We can’t be constantly as efficient as possible.

DANIEL: Okay, I want to talk about some other work that we’ve talked about. We did an episode years ago on semantic illusions. This was work from Professor Hartmut Leuthold at the University of Glasgow and a team. This is back in 2012. They were looking at processing of sentences like this: “Should it be legal for a man to marry his widow’s sister?” What do you think, Sasha? Should it be legal for a man to marry his widow’s sister?

SASHA: He’s dead.

DANIEL: You were quick on that one. That’s right. If a woman is a widow, her husband is dead, and therefore he’s not going to be marrying anybody.

SASHA: Exactly, yeah.

DANIEL: Nice. There was also a study by Mante Nieuwland and Gina Kuperberg from Tufts University. This is way back in 2008. They studied two kinds of sentences, there were pragmatically licensed sentences which are nice and they don’t throw you any curves. And then there are pragmatically unlicensed sentences. So, a licensed sentence would be, “In moderation, drinking red wine isn’t bad for your health.” That’s pretty straightforward.

SASHA: Yep.

DANIEL: Now, here’s an unlicensed one. “Vitamins and proteins aren’t very bad for your health,” which makes you stop and think for a second more than the previous sentence. I just feel like the “space concrete bricks” sentence is just super pragmatically unlicensed.

SASHA: Yeah, that’s true. And I guess it comes from the genre of a headline compared to normal discourse.

DANIEL: Ah, where things are left out, different words are used.

SASHA: Actually, because… Yeah, if you’re thinking of compressing information, a headline is actually just a compressed form of a story.

DANIEL: So, the format is also playing a role.

SASHA: Yeah, I think that’s also what’s going on. So, it’s trying to cut out all the unnecessary and redundant information and just get down to what’s the core, most informative things that we can pack into a short sentence for a headline. Whereas if you were discussing that in a conversation, you’d pad it out across multiple sentences and introduce each idea to give your audience some time to process what’s going on.

DANIEL: Okay, so this took us a long time because the words in the sentence are surprising. It’s pragmatically unlicensed, which makes it difficult to parse. And then, it’s also in the format of a headline where things are left out and that causes a bit of hangup as well.

SASHA: Yeah, I would say that’s a good summary.

DANIEL: Fantastic. Well, Sasha, I’m really grateful that you came up on Twitter and responded that way because now I feel like I understand a bit more about language processing and time.

SASHA: Great, I’m happy to help. Thanks.

DANIEL: Sasha Wilmoth of the University of Melbourne. How can people find out what you’re doing? Do you want people to find you?

SASHA: Yeah. So, I am on Twitter and then I also have a website where I post publications and stuff. So, on Twitter I’m just my name, Sasha Wilmoth, and my website is just sashawilmoth.com. And I’m on Google Scholar and all the usual sites as well.

DANIEL: We will have links up on the show notes for this episode. Sasha, thanks so much for hanging out with me and explaining stuff.

SASHA: Thanks so much, Daniel. Great to chat.

DANIEL: And now, it’s time for Related or Not. This time, our Related or Not theme is from Camden.

BEN: Camden, the place?

DANIEL: No, it’s a guy. Camden sent us this via SpeakPipe, which everyone should do.

BEN: Ooh.

DANIEL: Let’s listen.

CAMDEN: Hello, hello. This is Camden Parks contacting you from rural Illinois in the United States. I’ve been thinking about your Related or Not jingle, and it’s hard to get that, believe it or not, tune out ahead. So, I thought, let’s just think of something that’s radically different. And for some reason, I thought Jethro Tull’s Aqualung. [BEN LAUGHS] Unfortunately, I don’t know how to do musical accompaniments. So, you’ve just got to deal with my voice.

DANIEL: [BREAKING IN WITH THE POWER OF THE EDIT] Don’t worry, Camden. I got your back. I found a guitar track and I laid it over your singing. So, let’s hear that.

CAMDEN: [SINGING] Do these words share a root? Or are they merely false friends. This is etymology, done on the fly to no serious ends. Related or not. [SPEAKING] Yeah, and do with that as you will. Thank you and bye.

DANIEL: Thanks, Camden.

BEN: I’m going to have to replay that, because I’m going to remember [SINGING] this is etymology.

HEDVIG: Yeah, that was good.

BEN: [SINGING] No serious end.

HEDVIG: That’s very well done, Camden.

DANIEL: It was good. And you know what? The guitar track that I found, I’ve got to… I’m crediting that on the show notes, but I didn’t have to pitch it up. Camden, your pitch was impeccable. I didn’t have to do anything.

BEN: Oh, nailed it. Without backing. Good on him. A sincere Jethro Tull fan. And who wouldn’t be of a band, a rock band with a flute?

DANIEL: Very much. All right, our first one comes from Vehemently via email. KITCHEN and CUISINE.

BEN: Ooh.

DANIEL: You know cuisine comes out of the kitchen. Don’t you know.

BEN: It’s true.

DANIEL: In fact, in some places, the cuisine is the room.

BEN: CUCINA is kitchen in Spanish, is it not?

DANIEL: COCINA in…

BEN: COCINA.

DANIEL: Is it CUCINA in Italian?

BEN: So clearly in the Romance languages, there’s a link between CUISINE and KITCHEN.

DANIEL: Mhm. Mhm.

BEN: Does that transport over into English? Hedvig, you look like you already know the answer to this.

HEDVIG: I just know that there’s been a map of these two-word etymologies that’s been doing the round on social media networks lately. I can remember the image of the map, it features sort of orange and red colours over Europe, and all the lines are coming out of Italy, but I think they might be… They’re at least from like two different Italic dialects or something like that.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: And I’m not sure if they end up converging at some point.

BEN: I’m going to go not related because I feel like kitchen, with its K, just has a really different vibe. I’m sensing some Norse. I’m sensing some Germanic. Something quite different from the COCINA/CUISINE. That sort of like soft, lilty mouth sound.

HEDVIG: Ben, can you pronounce the two words that we’re doing for you, please?

BEN: Oh, but I’m probably pronouncing the Spanish one wrong. KITCHEN and CUISINE.

HEDVIG: Okay, so do you hear how both of them have a /k/ in them?

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Okay, fine, but, but, but… [HEDVIG SNORTS] [UPROARIOUS LAUGHTER] Wow, my stupidity got a snort out of Hedvig. That’s… I feel really spesh. That’s really nice.

DANIEL: That doesn’t happen.

BEN: Okay, you know what? Fine. But I’m sticking to my guns.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: That’s fair. I’m not saying you’re wrong. I’m just saying it feels…

BEN: Feels like you’re saying it a bit.

DANIEL: Sounds, not letters.

HEDVIG: I’ve been like brainwashed. Like, I think so much about sounds all the time that I’m bad at spelling. So, when you said that one of them has a sound that the other one doesn’t have and it’s a ka, I was like…

BEN: That’s wrong.

DANIEL: That’s the same sound. Are you saying then, Hedvig, that you think they might be related?

BEN: Go on. You got to say it after all that.

HEDVIG: Yeah. So, what if it could just be that the -CHEN is like a Germanic diminutive thing.

DANIEL: Oh, right. Okay.

HEDVIG: Or something. Yeah. Okay. I’ll guess that they are related, but I’m not so sure.

DANIEL: Okay. I thought yeah, they’re related. I’ll believe anything. And also, remember, we borrowed a lot of those kitchen words and food words from French.

BEN: Yeah, that’s true.

DANIEL: So, answer, Vehemently says they are related. They both go back to vulgar Latin. COCINA or CUCINA, so related.

BEN: Can we for a second talk about why it’s called that? Why is it vulgar Latin? And is there a prudish Latin? Like, how does that work?

DANIEL: Vulgar just means, like, of the people.

BEN: Right.

HEDVIG: And usually Vulgar Latin refers to, yeah, not as formal, not what you speak in the senate and maybe what was spoken later.

BEN: Like the laypeople.

DANIEL: The language of the people. Only later did VULGAR mean something bad. Because they people thought that other people were bad. And they are. Okay. Thanks, Vehemently, for that one.

Next one’s from Gordon. MINIMUM and MINIATURE. They both have MINI- in them. My answer was, of course they’re related. At least, I think the two MINIs are related. And I think they’re both related to MINUS. Mm-hmm.

BEN: Interesting. Now, I’m really inclined to say no here because it feels so obviously a strong link that why would it even be up for question?

DANIEL: You know what? I love how we started off playing Related or Not. But it really quickly turned to Are Our Listeners Fucking with Us or Not?

BEN: Yeah, yeah. It is just absolutely Prisoner-Dilemma shit all the way. And I think we are being fucked with. So, I am going not related.

DANIEL: Okay, Hedvig, your answer.

HEDVIG: I mean, we get to into the problem we’ve had before where, like, if part of the word is related, then sometimes Daniel has been like, [IMITATING DANIEL] “No, it has to be the whole word.”

DANIEL: Okay, okay, hang on. Can’t believe you gave me that voice.

HEDVIG: So, it’s MINIATURE and MINIMUM, right?

DANIEL: Let’s just say the two MINIs. Are the two MINIs related?

BEN: What we’ll say here is, yeah, exactly right. If MINI is shared between these two words, even if the second half of it is, like, wildly different, I’m calling it related. So, I’m claiming though, I’m putting my flag in the sand and being like, the MINIs are not related.

HEDVIG: It’s the A that is screwing with me, mini-a-ture. I’m going to say that they are related. Oh, my god. They’re both small.

DANIEL: So, I said related. Hedvig said related. Ben says not related because he suspects a trap. It was a trap. They are not related.

BEN: [EXCITEDLY] Yes, all that Dungeons & Dragons finally comes in handy.

DANIEL: MINIMUM just comes from Latin, minimum. That’s really straightforward, but then the MINIATURE…

BEN: That’s not coming from… That is.

DANIEL: That’s what it is.

BEN: It is just the Latin word.

DANIEL: What it is. But MINIATURE comes from something different. A different Latin word, MINIUM, which was a word for their red lead. There was a kind of lead, and it was red. And they used it in paintings. They would paint things red, like little tiny, teeny, tiny pictures in manuscripts with red paint, and those were called miniatures. I mean, yeah, they were small, but the meaning transferred from the red lead that they were painted with, the minium, to the size of them. And miniatures were then a thing that were really tiny.

BEN: That’s really cool.

HEDVIG: That’s amazing.

DANIEL: It’s possible that MINIMUM played an effect, that it had a little bit of a cross-influence, but they are not necessarily related that way. It could be a case where the two words group together. Thanks, Gordon, for mucking with us.

BEN: I caught you, Gordon.

DANIEL: Ben’s onto you, man. He’s done this.

BEN: It’s not paranoia if they really are all out to get you.

DANIEL: This one is from James on our Discord. If you do glass, you are a GLAZIER. Yes. So, James is wondering about GLASS, GLACIER. And I’m adding GLAZE… Actually, I’m adding GLASS. GLASS, GLAZE, and GLACIER. Do you think any of these are related?

BEN: GLAZE and GLASS definitely are. I can say that with a rock-solid certainty.

DANIEL: How do you think?

BEN: I mean, I can give you the… Because to glaze something is to put a microscopic layer of glass on something. So, glazed pottery has a very fine film of glass all around it. And then, other things that became glazed, which had that look, like a glazed ham or whatever, a layer of usually some gelatinous or kind of clear-looking thing on top of something.

HEDVIG: Sugar.

BEN: Yeah, exactly right, sugar. So, that for me is like a pretty, like an indelible link between the two. So, GLASS, GLAZIER, and GLAZE would all be related.

DANIEL: Do you feel that way, Hedvig, before we go on to GLACIER?

HEDVIG: No, I think that’s maybe true. I think everything has to do with ice.

BEN: Ooh. Interesting, interesting.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. Okay, interesting. There’s your glacier tie-in.

BEN: Because I was going to say GLACIER, no.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Well, have you ever seen ice and seen glass?

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: I have.

BEN: They bear a passing resemblance. [DANIEL CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: They do. Have you ever seen sugar sculptures, by the way?

BEN: Yeah, yeah, true. And look like having been to actual glaciers, they do have like an incredible sort of glass, like deep blue sort of… It’s pretty incredible when you see them. So, you’re probably right. I think. Yeah, most likely.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: I think they’re all related. I think it’s got to do with ice.

BEN: But, but, but, but. But. But. But.

HEDVIG: But.

BEN: Glass…

DANIEL: But.

HEDVIG: Yes?

BEN: …is a pretty recent thing.

DANIEL: It’s a bit different.

HEDVIG: Yes, I was thinking about that too. That’s why… And ice isn’t.

BEN: Yeah. So a glass…

DANIEL: Yeah, but metaphor.

BEN: Okay, so you’re thinking all of the various glass words we have have all come from GLACIER. That… I mean, I can imagine that.

HEDVIG: Not from GLACIER, from some word for ice.

BEN: Yeah, okay, sure. Which we then also applied to GLACIER.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: I think that GLASS and GLAZE were related, but I felt that GLACIER wasn’t connected. I felt like that was…

BEN: That’s what I said originally, but then Hedvig convinced me otherwise, and I’m going to stick with it because she seems real smart and stuff. She’s a doctor.

DANIEL: She is pretty smart.

BEN: Of language.

DANIEL: I’m… I’m pretty smart.

HEDVIG: Oh, god.

[PAUSE]

BEN: No, no. I’m sticking with that one.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: I might be dragging you down.

BEN: That’s okay. We’ll go down together.

DANIEL: Well, the joke’s on you, because GLASS and GLAZE are related. They both come from Proto-Germanic, *glasam, glass. But GLACIER’s on its own. That’s right!

HEDVIG: Is it really. Is it really.

BEN: Hang on, hang on, hang on. Proto-Germanic…

HEDVIG: That’s not very far back.

BEN: …had a word for GLASS.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm. They did. I guess they must have been making that stuff.

BEN: Surely, but hang on…

HEDVIG: You can make sand. You can make…

BEN: Oh, like obsidian and that sort of thing. Okay, fair enough. Yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Take some sand and potash and stuff, okay. So, it seems that GLACIER comes from old French glace, which meant ice, from a different Latin word, glacies, which means ice. And if we’re really going Proto-Indo-European, although Douglas Harper of Etymonline told us not to…

BEN: Yeah, he was just like, boo.

DANIEL: If we go back there, GLASS and GLAZE are both from a proto-Indo-European root, *ghel-, something like to shine. Whereas GLACIER and French GLACE, meaning ice, is from a totally different proto-Indo-European root, *gel-, meaning something cold or to freeze. So, GLACIER seems to be on its own.

BEN: Ooh, Hedvig…

HEDVIG: I’m sorry.

BEN: We went down together on that one. But are you sort of feeling clearly in this ancient linguistic tree, this shit is clearly all related?

HEDVIG: Well, I mean, I do agree with Doug that the further back you go, the muddier it gets.

BEN: The more ridiculous it becomes. Yeah, yeah. Or in this case, the glassier it becomes.

DANIEL: Through a glass darkly.

HEDVIG: But the way historical linguistics comparative method works, certain things, you get almost like a reduction in number of sounds the further back you go…

BEN: Yeah, yeah.

HEDVIG: …in some ways. You do pick them up in some ways as well. So, you don’t only reduce, but… So, things get more and more similar the further back you go. And then I think, I believe Daniel when he says, at least to our current knowledge, we cannot say that GLACIER is related to GLASS and GLAZE.

BEN: Fair enough.

HEDVIG: Fair enough.

DANIEL: That’s all. That’s all.

BEN: I’m just looking at your map of all of the kitchen words. It’s pretty amazing because normally there’s a bit more variance than that across all of those linguistic traditions, and they’re all very clearly related.

HEDVIG: So, for our listeners, I don’t know if Daniel’s going to keep this in, but I remembered the map about the kitchen words that I had seen and I posted in our little private group chat. Yeah, so it’s supposedly all from vulgar Latin, cocina or cucina, or coccina.

BEN: Any Italian looking at this map would absolutely spooge themselves to know that, like, all words for kitchen came from there.

HEDVIG: Oh, you’re right. Oh, and I don’t like feeding the Italians’ confidence when it comes to food.

BEN: They would just be like, [IN AN ITALIAN ACCENT] “Yes, of course. This makes much sense.”

DANIEL: Speaking of spooge, we are seeing people talking about glazing someone as a way of praising someone?

BEN: Daniel.

DANIEL: That’s where I see the etymology for that one. Nice, huh?

BEN: Daniel.

DANIEL: Anyway, the relevant sense is that of polishing.

BEN: Talking… speaking of vulgar Latin, Daniel, honestly.

DANIEL: Thanks to James and thanks to everybody who’s giving us Related or Not words. We’re having a lot of fun with it. Don’t forget, we’re doing them for our live show. You’ll get to vote for real. So, it’ll be fun.

[MUSIC]

[INTERVIEW BEGINS]

DANIEL: I’m here with Dr Gerald Roche from La Trobe University. He’s the author of a new book, The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet. Gerald, thanks for coming on and having a chat.

GERALD: Yeah, thanks very much. Really lovely to be here.

DANIEL: Wow, what an issue. What a topic. You’ve really tackled a pretty big thing here with some pretty big implications for the world.

GERALD: Yeah, I wanted to tackle a topic that I think is extremely important, the global crisis of linguistic diversity. And it’s a big topic to take on. So, we’ll see. I don’t know how it’s gone. Let’s find out, I suppose.

HEDVIG: I guess so. Maybe just as a quick beginner, if there’s anybody who’s not convinced that language diversity is a good thing or that language endangerment is kind of terrible, what’s the case for keeping minority languages around?

GERALD: Mm. So, the case that I make for keeping minority languages around is that you have to go through an awful process which is both politically oppressive and harmful to get rid of those languages. I come to these issues as anthropologist. I call myself a political anthropologist. And so, I’m less interested in the languages and what happens to them and what information they contain and things like this than I am in the people who speak them. And so, when I think about that question about like why diversity, why retain languages, my answer is that diversity is maybe in itself not the most important thing. What’s more important is the harm that is caused in the process of getting rid of that diversity and the sort of oppressive relations of domination that get enforced in that process. That would be my pitch to you and your listeners.

DANIEL: Okay. Whereas, I, as a linguist, would say, “Oh, language eradication is super bad news because we’re losing languages.” You’re actually saying language eradication is really, really bad for people and their social connections and their cultural knowledge and what happens to them.

GERALD: Yeah, exactly. I understand the kind of answers that other people give, but my concern is that they can also create justifications for destroying diversity if they can prove that they can solve that problem. For example, if you say that the problem with reducing linguistic diversity is that we lose valuable knowledge about the environment or humanity or something like that, which is an argument people make, well, then the counterargument is that if we can record that knowledge, then you can just get rid of the languages and it doesn’t really matter.

Another example is that people will say, “Well, diversity is good because it leads to high team functioning in a productivity sense.” If you have different people with different languages, they bring different perspectives. Again, if you can get that high functioning without the languages, then it doesn’t matter.

The last argument that people make along those lines is like the cognitive function one, that being multilingual is good for your brain. It slows down aging. It prevents Alzheimer’s, etc., etc. Again, if you can show that people can get those benefits without multilingualism, then you’re providing people with an excuse to just get rid of languages. That’s my concern with those kind of answers.

DANIEL: And what we’re saying instead… Well, the answer that I might give instead, if I’m thinking more along your lines, is if we’re seeing the loss of languages, it means that there’s something bad that’s happening way up the chain, and language is just one of the ways that this is coming out. Would that be right?

GERALD: Yeah, exactly. I think that there are specific things about language. Language is targeted in particular ways, but it’s often targeted alongside other things. And so, that’s why I think it’s important to think about what I call language oppression, which is what is driving the destruction of linguistic diversity. It’s important to think about it in tandem with and in relationship to other forms of oppression in relation to race, ethnicity, and so on.

DANIEL: Well, what kinds of oppression are we talking about? Since it’s the title of the book.

GERALD: [LAUGHS] Yes. So, language oppression. I’ll talk a little bit about that term and where it comes from, because it’s not my term. I didn’t invent it. It comes from a book chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages. The chapter has many authors, but the lead author is Alice Taff. So, she’s writing with a group of scholars who are talking about the relationship between Indigenous languages and health. We have this literature going back a couple of decades now showing us that retention and reclamation of Indigenous languages has a number of surprising positive outcomes for people’s health and wellbeing, and they kind of are talking about those relationships. And the argument that they make is that, well, the process by which people are deprived of their language is oppressive and harmful in and of itself. And so, when you reverse that process and you undo those relationships, that has a positive impact on health and wellbeing, which I think is correct.

So, to sort of focus attention on that, they use this term “language oppression” rather than “language endangerment”. And so, language oppression, they define as the coerced enforcement of language loss through these various means. And when I read that, it just kind of clicked for me. It made sense in terms of what I’d seen in the field over a number of years, but also in terms of the literature that I was working with coming out of anthropology, so anthropology of violence, the critical anthropology of the state and so on. So, it brings all of that together really nicely.

I like the way that it operates kind of as a replacement for “language endangerment”. So, I think language endangerment, the way that it’s described in the literature, is a real and important problem, but I don’t think that’s the best term to describe it if we want to have a proactive, solutions-oriented approach to stuff. Because when we say language endangerment, the image that I always have in my head is like a scary monster hiding around a corner, or it’s like there’s a weird glow on the horizon, we don’t know what it is. I don’t feel that the language endangerment literature, as much as it’s been useful and provided lots of insights, I don’t think it has managed to describe the problem in a way that charts forward a path towards what we actually need to do to intervene in the situation effectively on a global scale.

That’s what I think this idea of language oppression really does for us. It does that in two ways. One is the way that I mentioned previously is that putting oppression in the title helps us think about it as a political relationship along the lines of other political relationships that we’re already familiar with. We know that other forms of oppression exist. We know that they are not good. We know that they have been and can be successfully resisted. So, it puts our thinking in that frame immediately through that term.

And then, the other thing that I think it does is it sets up that binary relationship of oppressor and oppressed, which is really important for making analysis of what’s going on and what needs to be done. I certainly wouldn’t say that this is something which is done universally in the endangerment literature, but there is a tendency towards victim blaming in the way that the problem is framed. One of the ways that we see this is through this concept of language vitality. You turn on your linguistic thermometer and you measure the vitality of the language, and if the language doesn’t have enough vitality, then it’s on its way out, it’s endangered, it’s moribund, whatever. But it locates the problem in the language just through the way that we talk about it and the way that the criteria it uses are in terms of domain analysis, like the language is spoken at school, in the media, in business, in government offices, and so on.

It puts the focus on the language, but what actually needs to change is the broader context beyond the community and beyond the language. So, knowing that the language is not in school is important because that’s a massive driver of why people choose not to use and transmit a language. But the question is, why isn’t that language in school? Who said it can’t go in there? Do people want it in there? Do they really have that option on a legitimate level? So, language oppression, I think, draws our attention to those kind of issues, like who outside the community is pressing down on the community? Who is oppressing them? What are they doing? How are they doing it? And then, we can get into the complicated analysis of what oppression looks like in practice, because it’s often not the kind of direct, explicit violence that we are led to expect. So, that’s kind of what the book does, is like unearth what oppression looks like in this context.

DANIEL: I like how oppression is kind of how you’re advocating for language oppression as a substitute term for language endangerment. Because yeah, if you use the term language endangerment, it sounds so abstract. It’s like, “Oh, condors are endangered, pandas are endangered. Well, I didn’t really do anything, but nobody did anything to make that happen. It just happened.” And it doesn’t just happen.

GERALD: Yeah. And the kind of the irony is that the conservation movement and the climate movement have gone in a much more political direction now. So, you have climate justice movement and things like this. One of these memes that goes around that, which is like, “The X number of people who are producing X percent of the global carbon output have names and addresses.” So, climate activism has gone in this much more heavily politicised direction because we’ve realised that there’s a power dynamic that is enforcing this, that there are institutions and people with vested interests in maintaining this situation. And what is fundamentally needed is a change in those political relationships.

The endangered language movement started off aligning itself with environmental movements sort of as a way to gain traction, be more visible, to sort of jumpstart the thinking in terms of borrowing some of the tools.

DANIEL: It’s understandable, the work had already been done in that area.

GERALD: Yes, exactly right. And they wanted it to make sense to people. So, that approach made sense, although arguably there were other options available that weren’t taken. But leaving that to the side, I do think it made sense. But the movement that language endangerment was modeled on has shifted so drastically in that time, and I think it’s… Maybe we need to catch up with climate movement as it now exists in this much more politicised form.

DANIEL: Okay, well, now that we’ve drawn an express link between languages disappearing and political oppression, let me ask this question, and I’ve asked this question before to other people, but I want your take. Is all language death language murder, or do sometimes people just naturally shift away from their traditional language? Are they choosing, or is it all oppression all the way to down?

GERALD: Pretty much. Like, short answer is pretty much today, it’s all oppression all the way down. So, there are counterstories that you can tell. One of my favorite examples comes from Papua New Guinea. I think it’s the research of Donald Laycock. But anyway, there are these historical examples of, like… You know Papua New Guinea is this fantastically diverse part of the world. And there are these case studies where it looks like people have just stopped speaking one language and started speaking another for kind of laughs. That’s an oversimplification, but because they wanted to. They had these cultural values where diversity, differentiation, and distinction were all important, and they enacted that through these acts of extreme linguistic creativity. And they would collectively make these decisions where they would invert particular linguistic practices to start differentiating themselves from their neighbors. So, that has happened historically.

But if you look around the world today, it would be hard to find, really, an example of that kind of thing, and it would certainly be the exception rather than the rule. So, we have to understand the historical specificity of what we are witnessing today. If I go on what used to be Twitter or if I give a public talk about this stuff, there is always some contrarian in the audience who wants to say, “No one speaks Latin anymore,” or something like this. “And aren’t you just interfering in natural processes?” “Isn’t this just part of the way that the world is.” And it’s like, yes, languages change, and they change over time to become unrecognisable to their ancestor languages. And we know that this is a historical thing that has happened. Yes, yes, you contrarian, you are correct, you win the conversation.

However, that’s not what’s happening now. We have this kind of like new global situation which has emerged over the last 500 years or so, where Europeans started getting in their boats, going around the world, invading countries, doing genocide, dispossessing people of their lands, destroying cultures, enslaving people, etc., etc. Everything shifts in the world after that. And we get to this point, like very concertina-ed version of history where there’s this decolonial moment in the mid-20th century where post-World War II, setting up the United Nations, lots of colonised countries are calling for their independence from their European overlords, and the United Nations shepherds through that process. It creates a procedure for making new states so that colonialism is no longer a thing. So, they do that, but they do it in a way that essentially just devolves responsibility for colonialism to the new governments.

China is a classic example of that. China was set up as a colonial empire around the same time that Europeans were going around and doing it. So, China expanded into Tibet, into Xinjiang, into Inner Mongolia, off the back of silver that was being mined out of South America with a demographic explosion that was based on the potato, which had been taken through colonial trade network works into Asia and in response to expanding Russian influence in Siberia and Central Asia. So, China was part of that global colonial movement.

When it came time for UN-sponsored decolonisation, they just said like “China, you’re good. You have your country. That’s fine, you just keep that.” Like, they actually defined colonialism in a way that meant that you had to get in a boat and cross an ocean to do it. It’s called the Blue Water thesis. So, the Blue Water thesis was because if they hadn’t kept that, if they hadn’t used that principle, they would have had to break up all the post-colonial nations into smaller states. So, look at the Congo, look at India, look at Ethiopia, look at Nigeria, etc. If they’d followed through on the principle of actual self-determinations for self-identified peoples, 90% of the countries that exist in the world today would no longer exist. And that would have like… For the United Nations, that was not good. So, they just tweaked the definition of colonialism in such a way that most people in the world could continue doing it because they didn’t have a boat. So, China becomes a country. China is not a country. China is an empire with a flag and a seat at the UN. And that’s why we have this situation where Tibet is there, Xinjiang is there, Inner Mongolia, the Yi people are there, etc., etc.