We’re joined for the first time by Douglas Harper, proprietor of the world-renowned Online Etymology Dictionary (etymonline.com). He’s here to help us with our Mailbag questions, and even test us in a game of Related or Not.

In our Mailbag this time:

- What’s the difference between DEPENDENCE and DEPENDENCY?

- Why is TONGUE spelled that way?

- Why would saying a tongue twister in your mind be just as hard as saying it out loud?

- Why is STYGIAN the adjective form of the River Styx?

- Why are WHY and BECAUSE the same in some languages?

Timestamps

- Cold open: 0:00

- Intros: 2:01

- Questions for Douglas Harper: 9:16

- Mailbag questions 1: 24:00

- Related or Not: 41:24

- Mailbag questions 2: 1:03:20

- Comments: 1:14:18

- The Reads: 1:18:00

- Outtakes: 1:22:47

Listen to this episode

Video

Patreon supporters

Thanks to all our patrons! Here are our patrons at the Supporter level.

This time we are ordering our Supporters alphabetically, but after you run their names through the Enigma Machine. All the dials are set to Position B and Ring L (rotors VI I & III).

- Nasrin

- Kristofer

- Cheyenne

- Andy from Logophilius

- Alyssa

- Kathy

- Margareth

- Joanna

- Rodger

- Canny Archer

- Meredith

- Jack

- Tony

- Kevin

- aengryballs

- J0HNTR0Y

- Kate

- Manú

- James

- Rene

- Sonic Snejhog

- PharaohKatt

- Whitney

- Nikoli

- Chris L

- Rhian

- Raina

- Helen

- Larry

- Colleen

- Tadhg

- Ariaflame

- Amy

- Matt

- sæ̃m

- Steele

- Molly Dee

- Diego

- Elías

- Stan

- LordMortis

- Termy

- WolfDog

- Andy

- Lyssa

- Amir

- Ayesha

- Nigel

- Aldo

- Felicity

- gramaryen

- Ignacio

- Luis

- O Tim

- Rach

- Chris W

- Keith

And our newest patrons:

- At the Listener level: Debbie and Jane from Space

- And our newest free members: Jia, Rayley, O Basterfield, Don, Hanne, human, Polly, Alan, Rerisson, Jonathan, Timothy, Krish, and The Irish Literary Times.

Become a Patreon supporter yourself and get access to bonus episodes and more!

Become a Patron!Show notes

The surprisingly literal story of stealing someone’s thunder

https://www.bbc.com/reel/video/p08g1krn/the-surprisingly-literal-story-of-stealing-someone-s-thunder

Thanks I hate handburgers | Reddit

https://www.reddit.com/r/TIHI/comments/etpxqh/thanks_i_hate_handburgers/

etymology (n.) | Online Etymology Dictionary

https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=etymology

Corpus of Contemporary American English

https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/

When is an ‘o’ a “Scribal O?”

https://mbsteven.edublogs.org/2021/12/14/when-is-an-o-a-scribal-o/

Tongue twisters tie up your brain

https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2013/09/03/3839155.htm

Why tongue twisters are hard to say

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2013.12471

[$$] Functional organization of human sensorimotor cortex for speech articulation

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11911

WHY in different languages: 130+ Translation & Listening

https://translate.how/en/why/

BECAUSE in different languages: 130+ Translation & Listening

https://translate.how/en/because/

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

DANIEL: Everybody, I’d like to introduce you to Douglas Harper, the proprietor of Etymonline, the Online Etymology Dictionary.

BEN: My goodness.

HEDVIG: That’s an impressive thing to be.

DOUGLAS HARPER (DOUG): Hello. Nice to meet you all.

BEN: Yeah. What an impressive thing to have on your business card.

HEDVIG: Do you rake in really big money?

DOUG: Oh, sure! [LAUGHTER] No. The success is an utter accident. I did not set out to do any of the things it ended up doing.

HEDVIG: Really?

DOUG: I just lucked into it. I was shooting at a muskrat, and I hit an oil patch, and up came a gusher. It was like the Beverly Hillbillies.

BEN: That is such a good reference.

DOUG: And I’m standing there with, look at this look on my face, “What the hell just happened,” 20 years later.

HEDVIG: But it is great that you’ve put a lot of thought and effort into making it what it is, and a lot of people appreciate it, and it’s nice that you can support yourself through it. That’s really cool.

DOUG: It makes enough, and I’m grateful to it for that. It’s allowed me to help other people who are researchers who don’t ever get paid for anything and do all this work. I can give them money to help me find things out. So, you can sort of let it… I don’t want to say trickle down, but there’s an effect to making money online. But I don’t like making money. I’m just not good at it. I actually am doing this because I want to do it.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, before we eat up all our material, let me do the intro and then we can have a big old chat. Less about the money stuff, okay?

HEDVIG: Why less about the money stuff? It’s super interesting though, isn’t it?

DOUG: Yeah. I’m interested in MONEY. It’s a good word. We can explore.

DANIEL: Oh.

HEDVIG: Oh, MONEY.

BEN: Marxist.

DANIEL: I admonish you to stop talking about this while I do the intro.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: See? Yeah.

[BECAUSE LANGUAGE INTRO]

DANIEL: Hello and welcome to Because Language, a show about linguistics, the science of language. My name is Daniel Midgley. Let’s meet the team. First off, it’s Ben Ainslie. Ben, what’s the best etymology and why is it HELICOPTER?

BEN: It is not HELICOPTER. I am so bored of you being like, “Did you know the split comes before the P?” [LAUGHS IN AN EXAGGERATEDLY SILLY FASHION]

DANIEL: You’re taking my best lines.

BEN: My favourite etymology is one I heard just recently in just a really… I feel almost a little bit sort of grimy, because, of course, we’re a linguistics podcast, and it was some other sort of famous linguist person working in the media. And I was just like, “Oh, no, I’m supposed to be doing this cool work.” But it was the etymology of TO STEAL ONE’S THUNDER. That tickled me immensely.

HEDVIG: Oh, that was what’s-your-face from Countdown.

BEN: Yeah, from…

HEDVIG: Susie.

BEN: 8 out of 10 Cats Do Countdown.

HEDVIG: Yes. Yes.

DANIEL: Really?

BEN: Yes. It’s a longer etymology, so we might want to save that one a little bit later.

DANIEL: Okay. We’ll savour it.

BEN: It’s a longer story.

DANIEL: Awesome. I’m on tenterhooks. I’m stretched.

DOUG: Theater tech! It’s a theater tech thing. I’ll be a spoiler. It is a great one because there’s specifics. You meet people!

BEN: It’s one of those ones where like if someone told you it, you would be like, “Folk etymology, 100% not a chance,” and it’s true.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DOUG: And you meet real people in it and they’re fun. [LAUGHS]

DANIEL: We’re getting to you later. Second off is Hedvig Skirgård. Hedvig, do you have a favourite etymology?

HEDVIG: Do I have a favourite etymology? I kind of don’t.

DANIEL: It’s okay if you don’t. You can pick helicopter.

HEDVIG: No, I’m not going to pick helicopter.

DANIEL: Ben didn’t want it!

HEDVIG: Everything, minus helicopter now. I’m on Team Ben here. Um, I don’t know.

DANIEL: Oh, for once.

HEDVIG: I kind of like folk etymologies. And I believe that if they get ingrained enough, they almost become the etymology. So, like a lot of kids in Sweden would say, HANDBURGERS instead of HAMBURGERS.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: Because you hold them with your hands. And…

DANIEL: Psychological reality is reality.

HEDVIG: And I look forward to the day when that is what they’re called when I get a handburger at McDonald’s. I like folk etymologies. I think they’re really fun. I know they’re not scientific or true or real or whatever. But sometimes, if you can choose where to have fantasies, I think etymology… don’t have fantasies about how economy works or like citizenship or something. But if you have to have fantasies, I think etymology is a relatively safe space to have them.

DOUG: I agree and disagree, but I think you’re absolutely right. Folk etymology is kind of a put-down term. Something like handburger, it’s actually making sense of a word that doesn’t make sense in the context you’re using it. That’s actually how the language evolves. That’s the process. The other thing you point to, which I think is really important is, and it was iterated elsewhere, that this is or was the reality for somebody at some time. When you go to the past, and if you want to understand the past, you’ve got to accept a whole lot of that because they think things that we don’t think.

We know there’s nine planets. Maybe there’s eight. Now, I forget. Is there ten? But we know it! Whatever it is. They thought there was seven, and the sun and the moon were two of them. They were wrong, but their definition of planet was different than ours. You have to mentally get into the other head and see what they’re seeing to see why they’re using the language that way. That’s exactly how this whole process works. So, you’re right, you need to tap the right vein there.

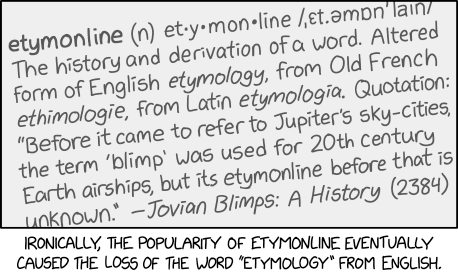

DANIEL: Nice. Well, that voice that you’re hearing is our special guest for this episode. Probably the only etymologist to have an XKCD cartoon about his work. It’s Douglas Harper of the Online Etymology Dictionary. Doug, thank you for coming on the show.

DOUG: Yeah. Sorry for busting in before the introduction.

DANIEL: Not at all. Not at all.

DOUG: Nice to meet you.

BEN: Is there a higher accolade than to have an XKCD comic about you? I reckon I could die a happy man knowing…

DOUG: I am still in the 20th century. Someone had to explain to me what that was. But when I did see it, I did recognize it. I have seen them, and they are extraordinarily clever things, and it is a great honor. After they pounded in my head, “This is a great honor,” I will say this is a great honor. It is actually.

HEDVIG: Yeah, it is definitely.

DANIEL: Very good.

DOUG: I’m more of an Onion reader myself.

DANIEL: Oh, yeah. Okay. Doug, do you have a favourite etymology example that you always go to when you’re talking to crowds, explaining your work?

DOUG: No, but I have a favorite answer to that question, which I get asked a lot, which is because… And it’s true, they’re all my children, you can’t really have…

DANIEL: They’re all my children. Yeah. That’s it. I knew it.

DOUG: And I used… There are ones that sometimes I say, “Oh, that’s so good. That’s got to be my favorite.” And I forget them. The one I come back to is the word ETYMOLOGY itself, which I guess it’s a natural for… I can’t pick anything else, really. And we did put a… I should say, two of us worked on it, put a little more effort into that to make it sort of a showcase entry for what we’re capable of doing. So, I’m going to go with the word ETYMOLOGY itself, which is great because it is an absolute opposite of what we call etymology now, but it’s a word for the thing itself. It’s not like chemistry and alchemy where it’s two different things. Etymology, its “true meaning”, that’s not what it does now. It’s the opposite of what it does. It’s dissecting meaning into particles. But the discipline flipped over 2000 years, but they kept the name, which is itself a historical story.

DANIEL: Well, we’re very pleased to be patrons of yours and to support your work, which if we’re honest, we use all the time on the show.

HEDVIG: Yes.

BEN: All the time.

DANIEL: Friggin’…

DOUG: That’s what it’s for.

DANIEL: That’s what it’s for. I’ve changed my mind. I’ve decided that my favourite etymology is ALGORITHM.

HEDVIG: Ooh, that’s a nice one.

DANIEL: Al! Because algorithms were created by…? Mr Algorithm.

DOUG: Friends called him Al.

DANIEL: See, you think that’s bullshit, but it’s not.

BEN: It’s exactly the same as SILHOUETTE.

DANIEL: Yep, yep.

BEN: Wow.

DANIEL: Lots of things.

BEN: That’s fascinating.

DANIEL: It was Al-Khwarizmi or Al-Khwarizme or something like that.

DOUG: Yeah. I can’t do that part.

HEDVIG: Most things that begin with Al are like a definite article in Arabic, like ALGEBRA.

DANIEL: Indeed he was.

DOUG: Yeah, it’s the Arabic definite article. Yeah, like Al Jazeera, the name, it’s part of people’s names, so, yeah, I got to incorporate…

DANIEL: There we go.

DOUG: Compare it to algebra.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: This is a Mailbag episode and we usually make these things bonus episodes, but we’re making this one available for everybody. If you like Mailbag episodes like this one, we got a whole heap more that you can listen to if you’re a patron at the Listener level. That’s just one benefit of being a patron. Another one is our annual mailout, it’s coming. Every paid-up patron gets one. And by the way, I’ve been getting the mailings, been making little videos about the packages that arrive at my house, the stickers and things. And so, if you’re a patron, update your address in Patreon so that you’ll get one. You’ll get our mailout. And if you’re not a patron, then why not head over to patreon.com/becauselangpod.

All right, we had some questions from our listeners. Doug, you ready?

DOUG: Yeah.

DANIEL: aengryballs asks, “How does one decide that a source has the first time a word was written down? You can’t read everything, especially not in English.”

DOUG: That’s a good question. And it’s the right question because people get fixated with the dates and they look at a date and they think they’ve seen the start of not just the word, but the thing, but they haven’t seen either. They’ve seen the first time that word was written down on a piece of parchment, sheepskin that had the luck to survive 700 centuries and be found and recognized and be dateable and be included in the corpus of books and dictionaries that I use or that I refer to. That’s not at all the same thing as the first time anyone ever used that word in English. But it’s the best we can do historically, so we’ve got to stick with it.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DOUG: It’s actually… Modern times are astonishingly combable now, thanks to digital libraries. I use newspapers.com. You can find… I can backdate everything in the old OED just using that which wasn’t around. OED editors never saw an American newspaper unless someone rolled it up and hit them with it. So, they’re not going to know this stuff, and you can get it now. That’s part of the reason I was able to… That’s what lured me into this site. It was like, “Here’s an open field, let’s go get stuff.” But further back, it’s not that hard. Old English, we might have, I think, fewer than a thousand actual texts remaining, and many of them are just copies of the same, Alfred’s Pastoral Care or something like that every church wanted to have, and there’s charters and it’s scattershot.

And even in Middle English, we pretty much… I don’t know if we might be finding more documents at some point. I think it’s been pretty well combed. I think we’re pretty confident that we’re seeing the first time it got into writing. But there’s going to be a huge gap with that and usage in almost every case, unless it’s a technical Latin term. So, once you cross about 1800, you’re into mass media and that’s when the explosion of… And it became impossible to comb, as a human being.

Machines are getting better. [HEDVIG LAUGHS] And I hate to say this because I detest this whole process of AI, but this is one of the things it could be useful to human beings for is if you funneled all this, not the… I’m talking about the past, not the present, into a siftable… What these are is they’re needle finders for the great haystacks out there that have been sitting there for a thousand years. Now, we’ve got the tools! And this is the fun part of this work. This is why it’s like Indiana Jones doing this. Without the gold.

DANIEL: Or the hat.

HEDVIG: So, for Swedish etymologies, about… Is it like… 1522 is like a limit where you can’t really go back much further because that’s when things start popping up in Swedish written sources.

DOUG: Right, right.

HEDVIG: And they still look very like German-y or they look a bit funny. So usually if you find something to 1522, people say, “Oh, this was first discovered in 1522.” But it’s like, “Yeah, you can’t go further back, so.”

DOUG: That has more to do with the technology of writing than with the language. Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah. What’s that limit for American and British English?

DOUG: Part of it. I mean, a lot of the Chaucer… We know when Chaucer died. We have a lot of Chaucer poems in manuscripts that we can date to 75 years after he died. But we don’t have earlier ones. You presume there were the earlier ones. The names are mentioned elsewhere, you know it existed. So, I will date that to within Chaucer’s life even if the document itself… The copy of the Canterbury Tales has a 1450 date on it, which is 50 years after he’s dead. So, there’s a fluidity to it. You can also…

For instance, one of the things King Alfred did in England in the 800s, he codified the law, which meant he went back and got all the old laws and gathered them in and copied them down as part of the new ones. Those laws are long lost. They’re from, like, the 600s. But we have that in Alfred’s… or we have a transcription of it, and the language is sufficiently different that you realize this is an older version of Old English. There are things scratched into sword hilts. There’s the guy’s name. Actually, it’s usually the name of the guy who made it. The guy who swung the sword couldn’t spell his name, but the craftsman who made it made sure he carved his name in the bottom because he’s the important guy. We don’t know whose sword it was, but we know who made it.

But that’s… It’s in runes, R-U-N-E, not ruins. At that point, when you drift back that far, you’re almost not one… Old English goes back to the continent. It’s not Old English anymore. So, the 410, 450 immigration period, then it isolates itself from continental Germanic. Then you can start to talk about there being a separate… But it’s not Old English because they’re not all talking to each other. They’re all over the place and they don’t even know each other.

HEDVIG: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DOUG: It’s not a language. It’s the beginning of an isolated population evolving into a language. So, you can’t put birth dates on the things.

HEDVIG: No, I like to think of that as that there’s… Like before the formation of nation states in the 1800s, most places are quite fluid and gradient. So, the limit between like, I don’t know, Dutch and German and Swabian or something is more gradual. And then when you get the nation states, things start to homogenise within those borders, and then you get things that people refer to as language. But before then, you have much more continuous stuff.

DOUG: And German is still… I mean the German that teach you in schools is not the German you speak in Germany…

HEDVIG: Let me tell you.

DOUG: And you can go town to town, and they have a slightly different German in each place if they still talk local. It’s absolutely fascinating because people don’t realize that our German is artificial. It’s the Prussian military needed a language to talk to everyone in. So, we get German, but it’s not what they speak.

DANIEL: Okay, let me move on to the next one. James asks, “It’s often said that etymology isn’t destiny. The true meaning of a word is not dictated by where it comes from,” as we’ve said. “Yet, there’s also a push in some cultivated prose to let go of words or phrases that have racist origins because of those origins. What’s your take on policies that avoid words because of the circumstances that generated them?”

DOUG: I’m not a fan of that. First of all, I’m not a fan of banning words in any… It doesn’t work. It doesn’t work. Look at what… The white supremacists have just laughingly found ways about bans on Hitler’s name. I mean, it’s so easy to do. You go back in history, history is full of cases where, “You’re not allowed to say this.” “Oh, yeah? Well, I’m going to draw a picture of that, that sort of reminds you of this.” You can’t do it. It doesn’t work.

I don’t think… If it’s a movement at all, it’s a fear knee-jerk reaction. What it is, is a game and it’s a part of the game that’s going on all over the internet all the time now. Can you convince people of something that’s not true? Can you make something and change the world by getting people passionately involved about it? I notice the trending words on the site, and they’re often those words, the words that are in the crosshairs now, like MASTER BEDROOM or something like that.

First of all, I can’t… It is entangled in the history of the people who use the word, which is, to our definition, at least, to a progressive definition today in America, inherently racist. All words from the past are tainted by the racism of the past. A word having been used one way or another way, it sticks with it. Now, there’s words like… There’s the word for someone who’s really stingy, the one that sounds like the N word. Everyone realizes…

HEDVIG: I don’t know which one that is.

DOUG: Okay. NIGGARDLY with a D. NIGGARDLY, it’s an old… It’s actually Scandinavian word…

DANIEL: It’s Norse, yeah.

DOUG: Yeah, but anyway, it’s an old word and you encounter it all the time and no one thought about it. But when you say it, it can sound like the other word. Christopher Hitchens, among other people, said, “I disagree with this, but I can’t use that word anymore. It just leaves such a dead smell in the air.” And that’s how words change, is: the sensibilities of people who don’t necessarily agree with the politics, that we don’t need this, we have other words, we can use other words. Let the people decide. The language isn’t going to be decided by an executive board. Not English, anyway; certainly not American.

BEN: I was just about to say the French would beg to differ. [LAUGHS]

DOUG: Yeah, I know! It’s great that they have that model going, so we can say thank you, not for us.

DANIEL: Yeah. And we do a lot of temperature taking on the show, and there are words that are offensive that we try to avoid. But then, there’s also words that have unfortunate histories. Like, I’m thinking of BULLDOZER.

DOUG: I’m surprised more people don’t jump on that one. To me, that one that smacks of slavery.

BEN: I don’t know it! Explain why BULLDOZER is problematic.

HEDVIG: I don’t know this either! Hey — I don’t know what we are talking about.

DANIEL: It’s not problematic. It’s just its origin is unfortunate.

DOUG: You have to go back in the family tree. Is it going to be Old Testament, we’re going to be tainted for seven generations, I don’t know. But it originally was a dose fit for a bull. It’s a beating dealt out to a particularly recalcitrant slave basically.

BEN: Wow.

DOUG: There are talks about it being done with a bull hide or a bull whip or something like that, but it might just be the notion of a particularly intense physical effort, which, over several jumps of meaning, ends up meaning a particular piece of mechanical equipment that moves dirt around.

DANIEL: But we don’t avoid it.

BEN: Fascinating.

DOUG: It’s from the 1876 election in the United States is where it became prominent, which was a nasty election. And that was the one where Reconstruction collapsed. And it’s all so deeply tangled. And really, the end of Reconstruction is almost uglier than slavery in American history, but it’s a dirty word. But I don’t… If you don’t know that, how can it offend?

DANIEL: And people don’t because it’s become…

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DOUG: It’s not inherent in the use of the word now. The air that comes out of my mouth with those sounds doesn’t contain that. It does now, because I know it.

HEDVIG: That’s the thing. But if the word has those connotations and people know it and they use it with that intention, like if they use derogatory words, for example, Jewish people or Black people with the intention to hurt, you can say that’s a problematic word, but it’s problematic because they’re actually…

DOUG: Only if you can be sure of that intention…

HEDVIG: …using it do something, right?

DOUG: And this is where it gets tricky, because if I don’t know that and I use it, I might even use it in a particularly flagrant way, it may look like I’m… We’ve all done that, where you do something, you’re like “Oh, my god, I just did the exact wrong thing and I didn’t realize it.” There is always the ambivalence. If a guy joins a hockey team and he takes jersey number 18, is he trying to celebrate Adolf Hitler?

BEN: Yeah, or like 88 and stuff.

DOUG: How do you know? How would you know?

HEDVIG: I am born 1988. And my first email that I registered had like, coolgirl88 or something like that. And when I went online and I saw a lot of other people have 88 in their username, I was like, “Oh, there must be a lot of people born the same year as me. That’s funny.” And then, like, there’s a lot of them. So, for the listeners who don’t know, one way that Nazis get around not being able to write like Heil Hitler, is used to write HH, which looks a bit like 88.

DANIEL: And it’s the eighth letter.

HEDVIG: So, all these other people online that I was encountering that I thought were just my age group were actually all Nazis. And it was very confusing.

BEN: That must have been…

DANIEL: What a year, huh?

BEN: …a pretty weird period.

DOUG: Got a good story out of it though.

HEDVIG: Yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Yep. I’m going to go on to Connie’s question. “Oftentimes, etymologies of a word are not clear at all. Rather, there are different hypotheses as to the origin of a word” — and I noticed that on Etymonline, there’s a lot of those going on. “How does one decide,” asks Connie, “which hypotheses are worth mentioning in a dictionary where space is limited even though it’s online?” Have you ever looked at one and just said, “Eh, I’m not putting that one in there”?

DOUG: No. Because I limit myself to the sources that are listed in the sources page, which I guess… I hate the fact that no one sees homepages of websites anymore. All you see is one entry and then you’re off. It explains this is cobbled from specific places. I don’t use the internet at all. Nothing that’s on the… If it’s in a book and if it’s in one of the books I’ve listed and used, they usually agree, I’d say like 90 or more percent of the words, the historical part of it, they agree. Not the asterisk part, not the PIE. And they’re consistent throughout. This comes from Latin, it’s pretty transparent. Where they disagree, I’ll note the disagreement. OED says this, but Century Dictionary says that, or Boutkan, who’s my Germanics guy.

HEDVIG: Mm-hmm.

DOUG: Generally, you want to go for etymologies with the more recent sources. There’s a tendency for people to… “Well, you say it’s this. I have this book from 1848, and it says…” The presumption is that 1848 is closer to 1400, so it’s going to be more right, but it’s not. We know nothing from the 19th century.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DOUG: They did the best they could. They’re heroic in their work, but you’ve got to use the newest stuff. And some of the things I wouldn’t put that in, they’re not in the books I’m using in here, but there’s an awful lot out there. It’s an academic discipline. It’s churning itself all the time. If you’re a senior linguistics major, you’re not going to write your thesis on agreeing with what they said in the previous generation. They overturn this PIE stuff constantly. So, I don’t trust that at all to be consistent 20 years from now. The historical stuff, I think, is pretty straight. It’s mostly transparent. There are some mysteries. People, especially online now, cannot accept that there’s sometimes not an answer we can see. We can’t see all of that.

BEN: Yeah, that’s so true. Even, I am guilty of going to Etymonline and just being like, “Ah, man.”

DOUG: It’s like the of “unknown origin phrase” is a clue to just start spewing ideas. “It could be this,” which is what we do with… And it’s fun. And that’s a human thing. That’s great, that’s a game, he’s just making a game of it. But sometimes, you have to accept. There’s a phrase, I half stole this and half me, “Who lusts for certainty, lusts for lies.”

DANIEL: Oh, that’s good.

BEN: Mm, I like that a lot.

DOUG: You are never going to get certainty about everything or even anything at the highest degree. You’ve got to let go of that.

DANIEL: That’s one of my favourite sayings: “You can have certainty or you can have wisdom, but you can’t have both.” I like that.

DOUG: Flipped sides of the same coin. Yep.

DANIEL: Okay. Well, thank you for that introduction. Thanks to our listeners for giving us those questions. Now, let’s get to some other questions from other listeners. You ready? Here we go.

BEN: Mailbag time.

DANIEL: Mailbag time. This one’s from Aldo, who says, “For some time now it has been bothering me that I don’t know the difference between the words DEPENDENCE and DEPENDENCY. In most cases, they seem completely interchangeable and synonymous. Today, I started to write one of these words, couldn’t decide which to use, and ventured off to the Google machine, which wasn’t much help. Can you help educate me? I’m utterly dependent on your knowledge.” So, I guess the first thing I’m going to ask is, what’s the deal with the -ENCE and the -ENCY suffixes?

HEDVIG: So, a sentence that I could make is like, “That person has a dependency on nicotine.”

DANIEL: Or would that be a dependence?

HEDVIG: Yeah, exactly. So, that’s one where I could do probably both. I think I would probably use dependency more. I don’t know why.

DANIEL: Okay.

HEDVIG: And then in language and linguistics, people talk about dependencies between words.

DANIEL: Yep. The connections.

HEDVIG: And say like, “This word is dependent on that one, they have a dependency.”

DANIEL: It’s always DEPENDENCY for that. I’ve noticed this.

HEDVIG: For me, I think I’m like very strong DEPENDENCY on that.

BEN: I would have attributed just purely intuitively that DEPENDENCY in a form that isn’t interchangeable with DEPENDENCE is something within a structure, within a thing you can map out in some way, whether that is coding or linguistics or literal, actual fricking architectural drawings or something like that. Whereas DEPENDENCE, in situations where it’s interchangeable, is when you’re talking about things that people can have and softer, less definitive, kind of structurally organised things. So, like an addiction can be a dependence or a dependency and that sort of thing. Which makes me suspect that maybe DEPENDENCY came first and then we’ve kind of retroactively applied it to like softer, squishier, more human fallible regions. I don’t know.

DANIEL: Interesting. Okay, well, Doug, what do you got?

HEDVIG: Ah, yeah.

DOUG: I think about it historically and that the difference is that the one is closer to the Latin form of the word and the other is closer to the French form of the word. With dependentia, it’d have the vowel sound at the end in Latin, and the French would just lop that right off. These pairs tend to come in at different points in English’s history. In the Middle English they’re getting the French form. After 1500 or so, they’re starting to look at classical Latin, really look at it and say, “Wait a minute. We have this…” It could come in by different channels, one can be popular, one could be highbrow. You end up with two forms of the same word because of our language’s braided history. And then, what do you do with them?

BEN: So, are we landing on: they’re mostly interchangeable?

DOUG: No, once you realize there’s two, then you start to: “Okay, well, we use this one for this and we’ll use that one for that.” There are cases like RADIANT and RADIANCY, or you have really different directions, but it’s rare to get everyone to agree to do that. Now you see, it started out in the Middle Ages, they’ll start to use this one this way and it’ll either… Sometimes, it completely flips because they’re alike enough. There’s nothing inherent in the form of the word that tells you it’s for that meaning and not this meaning. It doesn’t really help you distinguish. So, they keep getting confused and you do end up… And over time, it will be a different split, but there will be those subtleties. But they may not be the same throughout the language and they may not last more than a couple of generations.

DANIEL: Hmm.

HEDVIG: Do you know anything about the current split? Like, the things were talking about now like Ben said that, like, “Oh, one is like in a system and one is like a human has one.”

DOUG: That would not have been the way they thought in the Middle Ages. I think it grows out of the psychological… Psychological analysis changed the language a lot because you were talking about people’s behavior in different terms. You had a whole different playbook for everything. This is from the… I would guess that’s 1920s or later, maybe even 1960s, that split between physical dependence versus psychological dependence. They would have done spiritual and physical in the past, but it’s a way you can use two words.

HEDVIG: Mm.

DANIEL: Yeah. And I decided to try to find out if there was any sort of pattern nowadays. So, when I try to answer questions like these, I always go to the COCA corpus, the Corpus of Contemporary American English, and I just look at the words that occur near the words that I’m looking for. So, I looked for words near dependence, and I found these nouns: oil, alcohol, drug, abuse, fuel, government, and fossil. Those are the words that occur near dependence.

BEN: [LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: So, that sounds like a relationship between two things. So, like, Qatar is reliant on oil, it has a dependence on oil.

DANIEL: That’s the kind of thing you’d see, “Oh, I’ve got a dependence on alcohol.” Then, I looked up DEPENDENCY just to see if the word neighbourhood was different. I found just the same words in a different order. I found government, welfare, oil, drug, alcohol, ratio, culture, and theory.

DOUG: Yeah, they’re confused.

BEN: It sounds like we’re in pretty fuzzy, interchangeable territory then.

DOUG: I think… Okay, here’s one way to look at it. Is it one of them is positive and one of them is negative? “I depend on you.” There you go, I think that might be what’s going on.

HEDVIG: I was just going to say the same thing. I thought the first one sounded more negative.

DANIEL: Okay.

DOUG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay.

DOUG: “I’m dependent on you. Thank you so much.” “I’m dependent on alcohol.” “I hate alcohol.”

DANIEL: Well, it sounds like we’re saying that the words haven’t really isolated themselves into different neighbourhoods yet. Maybe they will in a hundred years.

DOUG: You know what’s interesting though is look what we just did. We have all these sources. We have the whole internet for us. We sat here, we were BSing with each other. “I bet it’s this.” “No, I bet it’s that.” That’s what people do. That’s the human… That’s the fireside experience of being human. It’s great to be able to know everything, but it’s also great fun to try and see if you have enough in your head to figure it out.

DANIEL: Well, thanks, Aldo, for giving us that question. This one’s from Kate on our Discord. “Why is TONGUE spelled that way? Did it used to have two syllables? I keep seeing it misspelled T-O-U-N-G-E, tounge.” Oh, I like the colour of that couch, it looks a nice tounge. “Which makes more sense,” says Kate. So, what’s up with tongue? Why is tongue spelled that way?

DOUG: Because history. This is the history of the language. The French trying to wrangle this sound into English and the English trying to make… As it changes. Can I share screen? Or do you want to share the Etymonline entry for tongue? Because that’s probably easier than me trying to…

DANIEL: Sure.

DOUG: …barge through it.

HEDVIG: Because it’s a very similar spelling to LANGUE, like language.

DOUG: Yeah, I’d have to… It’s… Something happened to it.

HEDVIG: Langue, tongue.

DOUG: It didn’t evolve the way it was supposed to. It got knocked off. Something got in the DNA. It must have seen an atom bomb go off or something, it came out all wrong. But this is the thing, this is where people say English is illogical or absurd or whatever, the results can be, but the processes are still the right processes. They just went wrong in certain cases, which will happen.

All right, I’m looking at the entry. Yeah, old English. Old English. T-U-N-G-E, which is how we ought to spell it, right? That’s how we would. That’s probably how the kid in second grade spells it and gets a D. That means the same thing, Proto-Germanic. So, you’re looking at basically the same, the Germanic, the German Z, that’s natural. Ignore the PIE. Something happens in English. The second paragraph, by normal evolution, it would be tung.

DANIEL: T-U-N-G.

DOUG: Right. And the O, we’re not worried about the O. But the O comes… it’s a scribal trick, I think mostly because when U… Did… you guys did this right? That the U and O used to run together in the old scribal hand, so words with U, M or U, N, they turned it to O. That’s how WORM gets an O and come and lots of other words get an O that way. Because if you look at… This is the great part of the research. You look at the old manuscripts and you say, “Okay, I see. Yeah, there is a problem there. They had to do that or else you wouldn’t be able to see it.” They ran everything together so much. Anyway, that accounts for the O.

And in the 14th century, this is when they’re looking toward Latin again, they’re just now trying to get… G is a tricky letter. French does it differently than English does. Getting French and English G’s to agree it’s a challenge, or apparently was. They somehow wanted to get that it was not TONGE but TONGUE and that’s the best they could do. And even the OED like basically does a face palm over it. [BEN LAUGHS]

But it shows you how language works and it’s not done logically. The question is logical, the answer cannot be logical because it’s the mass hive mind working… Not even working, it just… sounds are tumbling out of its mouth and then someone has to try and figure out what letter goes with that sound.

HEDVIG: And also, if you were to transcribe things into letters 100%, like that one sound is always spelled the same way, etc., then what do you do when you get language change? So, you write down how it’s spelled at one point in time and then that’s pronounced differently over time and then your spelling has to catch up, but that’s very hard to do. So, the way I think about it is that a lot of the writing systems that is the most transparent as it’s called where the letters and the sounds have like almost a one-to-one correspondence, those are often the most recent writing systems. So, like Turkish for example is like relatively recent. So, they have fossilised however Turkish was spoken in… and I’m going to forget the exact year, but it’s in within the last hundred years when they changed their writing system.

DOUG: 1920, I think. 1920, 1922, 1923.

HEDVIG: Yeah, something like that.

DOUG: Spelling is a modern invention. Shakespeare never misspelled anything, he couldn’t. There wasn’t a spelling. Most of the time I’m dealing with English, it’s pre-spelling.

HEDVIG: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that’s a good point too.

DOUG: So, these kind of niggling tricks that happens [DANIEL LAUGHS], that’s modern and it has nothing to do with the organic language. Your mouth doesn’t care how you spell it.

HEDVIG: And also, sometimes in old writings you can get the same sound or word spelled differently in the same text. So, one person is writing a letter to someone else and they’re just like, “Well I feel like putting an H in here but I’m not going to do it later because, like, I forgot about it.”

DOUG: Also, it’s a real clue to linguistics because they’re trying to write it. They actually are trying to in many cases wrestle the etymology and the phonetics into one word. And you can actually picture the scribe sitting there with a pen thinking, “Wait a minute. Does this have a U in it or not?” It’s like in a moment in history that comes through in that one letter. And they’re just doing this on the fly and trying to make it work, and we’re stuck with the results.

DANIEL: Thanks to Kate for that question. This next one’s from Bill via email, who says, “I had some sitcom on and a character was doing a vocal exercise. A proper cup of coffee in a copper coffee cup.” Let’s all say it together.

IN UNISON, BADLY: A proper cup of coffee in a copper coffee cup.

DANIEL: Well done, team.

DOUG: That was horrible.

DANIEL: “Later in the day,” says Bill, “I realized I was having trouble saying it in my head, making the same goofs I’d make if I were trying to say it out loud quickly. A copper proper copy cup of… all those, but why? I guess even though I knew that the challenge of a tongue twister is not that it actually twists your tongue, I did assume that the difficulty of reciting one was physiological. It’s not like I have any trouble typing it correctly after all. I just double checked. Thanks, Bill. P.S. My wife has pointed out that maybe this is just me since I’m prone to incidence of aphasia for migraine-related reasons. Whoops.”

So, I guess the first question is, do you, all of us, do we have trouble saying tongue twisters in our head? Does it come out wrong? Let’s just try one now.

[PAUSE]

HEDVIG: I’m having trouble the longer they are because my short-term memory is struggling to remember what it is. [BEN LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Well, what about “unique New York”? That’s short.

[PAUSE]

BEN: Yeah, I don’t have a problem with that in my head.

HEDVIG: That’s a little bit tricky. But I am also prone to migraines and sometimes have longer word retrieval. But I also have a tendency when I type to do phonological things. So, like if there’s an M that comes before a D, I’ll write N instead. So, I’ll like do phonological processes, but with my hands, which doesn’t make any sense unless my phonological brain is engaging more than it “should.”

DANIEL: Sounds like what you’re talking about is that whatever’s going on with language is also going on with our brains.

DOUG: You have an inner narrative. You hear… I do as I’m looking and there’s sort of like a sportscaster or something in my head saying this is happening, but your thoughts form in words.

HEDVIG: Some people, but some people don’t, right?

DOUG: Yeah. I always wonder, does everyone? This really isn’t, I know it, this is not my… This is Chomsky territory, I don’t do this, but this is psychology of language. And it is an interesting question because I found that doing that the more, I did it, the easier it got to do it without any stumbling in my head. If you say it over and over in your head, it gets fixed there. And you’re right, the brain shouldn’t tangle over things that only involve the tongue. There should be no brain difference.

HEDVIG: But I think… I mean, I know that psychologists nowadays don’t really believe in this mirror neuron theory that when we engage different parts of the brain, we actually pretend that we’re doing the motor things as well. So, if we look at someone who’s like jumping, that part of our brain is like, “I’m going to simulate jumping,” and do little jumping things?

DOUG: Like a dog in its sleep.

DANIEL: When did we stop believing in that? I thought that was still…

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DOUG: No, who’s this “we”?

DOUG: I thought they stopped believing in that.

DANIEL: We kind of don’t. I haven’t seen it talked about much. I haven’t seen an express renunciation, but I…

HEDVIG: We need a psychologist for this!

DANIEL: …it’s true. I haven’t seen it for about 10 years, that’s for sure.

BEN: This might be the next multiple intelligences.

HEDVIG: [TYPING INTO A SEARCH BAR] Are mirror… no longer cool?

DANIEL: No longer cool. That is true. Well, let me get to some work that I found while we’re looking at mirror neurons. This one is from Dr Christopher Bushel from the University of California and a team, published in Nature way back in 2013. In this paper, they looked at three people — N of three — with epilepsy. Now, these people’s brains were rigged up with electrodes because they were undergoing presurgical electrophysiological sessions.

They got these people to say some syllables and then took a look at what was happening in their motor cortex just to see if there were any patterns. They found some pretty interesting patterns. They found that there was a lot of overlap in the places that were doing the work. They saw that there were front of the tongue sounds like /s/ and /ʃ/, there were back of the tongue sounds like /g/, and then there were lip sounds. They also found that the vowel sounds were a little bit different in the brain depending on whether your lips were rounded or not. Co-author, Dr Edward Chang, says this implies that tongue twisters are hard because their representations in the brain greatly overlap.

So, for our discussion, what this means is that what’s going on in the mouth is very similar to what’s going on in the brain, which would imply that it shouldn’t be surprising that you can’t really think tongue twisters any easier than you can say them.

HEDVIG: But does that mean that people who don’t have an internal monologue, which some people say that they don’t, I still don’t understand. I find it very hard to assess, A, if I really do because I don’t like hear a voice, but I think there are words. I don’t know how to explain it. But I want to know, like people who say that they definitely hear nothing and also maybe see nothing “inside their minds,” do they then have an easier time thinking about tongue twisters?

DANIEL: Sounds like we found a new research area.

BEN: Yeah.

DOUG: I had a Deaf friend once and tried to ask that question, but didn’t even know how to frame it in a way that she understood what I was looking for. I think that would be where you’d find out. What do Deaf people do?

HEDVIG: I bet there are “tongue twisters” in sign languages, right?

DANIEL: Yeah.

DOUG: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Like, combinations that are hard to get to quickly or that are very similar to each other, so you have to really make sure that you do them differently.

DANIEL: That would make sense. That would make sense.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DOUG: I-mutation is basically the same thing on a mass scale.

DANIEL: I-mutation?

DOUG: I-mutation. MICE instead of MOUSES.

HEDVIG: Oh, you mean like that.

DOUG: It’s a mouth trick.

DANIEL: Yeah.

DOUG: Supposedly it’s because you’re too lazy to jump to one sound and then back to the same. It’s explicable.

HEDVIG: Yeah, it’s like vowel harmony.

DOUG: Right. It’s explicable, basically mouth laziness, as I call it. But that’s the same process.

HEDVIG: Effectiveness is how I, as a self-identified lazy person…

DOUG: You guys are too easy on the mouth.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS] Thanks, Bill, for that question.

[RELATED OR NOT THEME]

DANIEL: There’s our Related or Not? theme song by Hugh. Thanks, Hugh, for that. It’s time to play Related or Not? The game that we were born to play with this man.

HEDVIG: What?

BEN: Hang on, hang on. How can we play this game with Doug? Like, this is like putting me in a ring with like a Mike Tyson in his prime, man! And I’m just pudgy old me being like, “Geez, Mr Tyson. Sure is…” [MAKES GETTING SMACKED SOUNDS]

DOUG: Hey, your shoes aren’t tied.

DANIEL: I could score a point off Serena Williams. Doug, what’s your comment on that?

DOUG: It’s funny, I’ve been doing this… This is the natural game. If you’re on this topic, I put it on a blog I had back in 2003 or something. I get to feel queasy about it because it implies, first a binary answer. And the answer is often, as we all know, we don’t know, or maybe yes, maybe no, or we know this one, but we don’t know that one. There’s like five possible logical iterations of an answer to that question. And also, I’ve become really, really concerned about people not understanding the difference between the historical etymology and the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mudhole, which is where they…

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

BEN: Mudhole, I like that.

HEDVIG: Those are very different.

DOUG: Like the one we were talking about before, FLOUR and FLOWER. There’s a question, is identical the same as related? I guess it is. But their clean historical evidence trail says yes. You can look at the divergence of form as you go back in time. But once you hit that ground level and you’re into asterisk territory, everything is uncertain. It is impossible to have a certain answer. It is just not intellectually honest to say it’s the same material you’re working.

HEDVIG: It’s not the same material but there is such a thing as things that historical linguists still are more sure about than others.

DOUG: Yes.

HEDVIG: So, if they see a regular pattern again and again in lots and lots of different words between two languages, and they see something similar for this pair, and the meanings are somewhat similar like, I don’t know, a pot and a bucket, you could be like, “Well, it seems very reasonable.” But you’re right, they can never be 100% certain.

DOUG: Grimm’s law is real. Grimm’s law is real. Grimm’s Law works. It’s all, but they… First of all, the PIE answers, since I’ve been doing this have changed enormously. I was using the old Watkins book from 1999, the second American Heritage Edition. And by the time I’m picking up these Leiden books, 2007, 2008, the answers are… I don’t know if the answers are different. These guys are giving different answers. And you start to see the pattern of what they’re doing. They’re looking back and saying, “Wait a minute. You’ve taken every modern Indo-European word and tried to find a PIE root. What if they got the words from the people who were there before the Proto-?” So that’s now the tendence, which is probably why it’s probably good, but it throws everything in turmoil again, and once again, everything’s uncertain.

HEDVIG: Wait, did you say that’s now the tennis?

DOUG: Tendence. Tendence.

HEDVIG: Tendence! Okay, sorry.

DANIEL: Tendence. Oh, I thought you meant TENDENCY.

DOUG: Okay, I probably just… lazy mouth, you know, it just happens.

DANIEL: Ah, there you go. Ben, you don’t have to worry because Doug is going to bring us some words.

BEN: Ah, Mike Tyson is officiating the fight. That makes way more sense.

DANIEL: He’s the ref.

HEDVIG: He’s the referee.

DOUG: That’s the only fair thing. Who’s got more money? Who’s got more money? I’m out of work, you know, I’ll take bribes. I was going to do this on my own. I can’t share with you because I made a little video, but is a STEPLADDER like a STEPSISTER? I see an old carpenter joke. “This is my stepladder, I never knew my real ladder.”

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay. Okay. I’m going to recuse myself because I think I know this one.

DOUG: We talked about this.

DANIEL: [LAUGHS]

BEN: I am going with not related.

DANIEL: Okay. Any reason for that feel?

BEN: I think that the STEP in STEP-PARENT or whatever is likely to be a lot older than the STEP in STEP-LADDER. And I’m also just struggling to understand how… I don’t know the conceptual link between a STEP on a ladder and the STEP in STEP-SIBLING or STEP-PARENT or what have you.

DANIEL: Somebody stepped out and then the step-parent stepped in.

BEN: Oh, I guessed that.

DOUG: Or you’re a step lower than the regular.

DANIEL: Oh, okay. A step higher.

BEN: Yeah, I’m still going with no, I just…

DANIEL: Okay, okay.

DOUG: We’re making stuff up now. We’re making stuff up. Maybe it’s because you have to kneel down in front of the carriage while the real person steps on you to mount it, so you’re the STEPSON.

BEN: Hedders, what do you reckon?

HEDVIG: I have a couple of thoughts. So, the only languages that I know these words in is Swedish, where the word is related to STYV. So, it’s styv father, styv sister, etc. Or sometimes nowadays people say BONUS.

DANIEL: I like that.

HEDVIG: I have a bonus dad. I have a bonus sister.

DANIEL: A bonus mom. That’s good.

HEDVIG: Or they also used to be pretend or plastic. I have a plastic sister. Like, not real…

DANIEL: Oh, dear.

BEN: Oh dear.

HEDVIG: But I think bonus is getting more common. Like, if you marry someone who already has kids, you say, I have bonus kids…

DANIEL: Which is nice.

HEDVIG: …which is nice. So now, I’m trying to think of STEP, but I do think that it is like one step away from a real “full sister.” I think that is the STEP, so I think it’s the same STEP. So, I’m going to say they are related.

DANIEL: All right, Doug, hit us.

DOUG: That’s the best guess. If I didn’t know, I’d say that’s a good guess. You want me to read through the answer then?

DANIEL: Sure. Just do what you do.

DOUG: All right.

HEDVIG: Rip off the band aid, tell me if I won.

DANIEL: Who’s right?

DOUG: You won my vote for the best wrong answer.

[LAUGHTER]

The question we’re really asking is, are the STEPS in both of them thought to be at some point in the past from the same root word. The form of it isn’t much help because it’s not like when you can trace it back and they start to look different the further back you go. STEPLADDER, that only is from 17th, 18th century or so. It takes you back to the verb, STEP. The Middle English, it’s Old English, straight Germanic, exactly what we use it for now. Take a step, move the legs and feet, and it’s consistent throughout Germanic, stappjan in German.

And then, you go to PIE, it sort of disappears in the mud, but when you switch over to the other STEP… It actually it was a word of its own in Old English. It had a verb, arstiufen, bestiufen, bereave, deprive of parents or children. And the original connotation is presumed to be of loss. And it goes on back into this… Again, you’re back into guess country with PIE. But the sense of it moving is transparently not about stepping. So, I think it’s safe to say with reasonable certainty these are not going to prove to be related if we could see the whole picture.

DANIEL: So, a step-parent is a bereavement parent.

DOUG: It involves a loss. There is a loss at some point in the story, and this is an element of what creates this new relationship.

DANIEL: All right, one for Ben.

BEN: I’m hearing that I got that 100% correct in every way.

HEDVIG: Oh, so…

DOUG: ORPHAN. ORPHAN is a similar thing. Orphan has an idea of passing… Someone was responsible for everyone in old communities. And if you didn’t have parents, you were a problem because no one’s responsible for this kid. So, they were very careful to maintain some sense of who’s in charge of this one. These relationships mattered in a community trying to survive. It’s funny because… You’re standing back in… Beyond that, pre-Roman.

HEDVIG: So, is a stepfather then a bit similar to a widower in a way that you’re assuming that they’ve lost their wife and/or kids?

DOUG: Something… yeah. Yeah.

HEDVIG: And they now as quickly as possible have to join up to another unit.

BEN: Shackle themselves to a fresh victim.

DOUG: Pretty much for food. Someone who will save you from the wolves. If you look at ORPHAN, the entry for ORPHAN does that too. It basically was a child bereaved of both parents, and it apparently comes from word that has to do with deprived of status, bereft. It’s a separation and loss word.

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Okay, that’s one for Ben. Let’s go to our next one. Have you got another one for us, Doug?

DOUG: Well, let’s see. I wonder. I hit this lately. I’ve been editing the UN- words, which is a nightmare. I’ll tell you about that. It’s hallucinogenic because it’s the entire dictionary with the word UN- stuck in front of it. So, I’m doing the same and it gets surreal. And then you hit UNGOOD and you realize that’s what it is. This is about making things the… All those old English words like UN-GLAD for miserable and UN-JOYOUS for… This is 1984. You freak out in the middle… This is where you freak out, in UN-.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah, yeah.

DOUG: Double plus un-good. Why do we need the word BAD? BAD is a negative word. It’s a bad sounding word. We have the word GOOD, that’s all we need, you just make UN-GOOD, who needs BAD?

HEDVIG: Double plus un-good.

DANIEL: Double plus un-good.

DOUG: Right. And then, we’re in hell. Well, we’ll be there in a week, so. But what I came across, and it surprised me because I’d forgotten it, was UNGAINLY, you know the word UNGAINLY?

DANIEL: Yeah. Kind of gawky.

HEDVIG: Yes.

DOUG: Me and technology is ungainly.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: A newborn horse.

DANIEL: Yes.

HEDVIG: Like, it seems to involve having long thin limbs.

DOUG: As we use it.

HEDVIG: Is that true?

DOUG: It’s changed. But is it related to AGAIN?

HEDVIG: Sorry, you meant the word AGAIN. Like, “I’m going to have another coffee. I’m going to have coffee again.”

DANIEL: I really thought you were going to tie it to gain. Okay, we’re talking about AGAIN.

DOUG: GAIN is Latin, right?

HEDVIG: That’s so funny, because when we do this game, I always write down what the words are. And I was trying to spell UNGAINLY and I was like, “I’m not sure about this.”

DOUG: That’s a good sign.

HEDVIG: But I did put in GAIN like the same way as AGAIN. I did spell it like that. Now, A- in like Greek and stuff like that is also like opposite. So, like…

BEN: Hang on, you’re giving us all the answers before we’ve put our answers in! [DOUG CHUCKLES]

HEDVIG: Well, but I don’t know if this A- is that, right?

BEN: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. I feel like you’re engaging in psychological warfare. You’re just throwing little bits and pieces out here to just leave us all…

DOUG: Separate corners, separate corners. Tyson breaks in. [DANIEL LAUGHS]

HEDVIG: This is why my husband likes to be on the same team as me when we play board games. Because when we play games — what’s that one called? Codenames — I will actively try and psych the other people out by pretending that I’m helping them to guess.

BEN: You’re a monster, is what you’re saying.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: I want to hear Daniel. I want Daniel to put his money on the table.

DANIEL: My thinking is that the first thing I thought of was, “Hang on, what’s the relationship between GAIN and AGAIN?” And I suppose that… I think that those two are related. You do something to the benefit. You do something so that there’s more of something. There’s more coffee. “I gained a coffee, I had it again.” But UNGAINLY, my first instinct is not… It’s just like two consonants and a vowel or two vowels, GAIN, anything could come to resemble that over a few centuries. So, I’m going to say nah.

BEN: I reckon yes. And I reckon yes not because they’re directly related like I don’t think one is necessarily the opposite of the other, but I’m wondering if the GAIN unit is the linkage here and in some way UNGAINLY once meant to literally like maybe to lose stuff. To be forgetful or like a bit of a space cadet or something like that. A person would be ungainly if they were always walking around being like, “Oh, no, where have I put my pocket watch?” And all that sort of stuff. And so then, like you were saying, Daniel, AGAIN could be related to GAIN. So, I reckon there’s a connection there.

DANIEL: All right, Hedvig, what’s your answer?

HEDVIG: I think the GAIN path is a red herring. I don’t think that’s related. And I’m thinking it’s… I’m going to guess that it has something to do with walking and that the GAIN thing has to do with walking. Like, go, gone. And that they are related. And that the UN- and A- are somehow…I don’t know the nitty-gritty, but that’s all I have, so related.

DANIEL: Okay, I’m the only one that’s unrelated. Ben and Hedvig think related. What’s the answer, Doug? Because we know that there are certainties in etymology.

DOUG: Apparently… well, they are related.

DANIEL: Goddamn it.

DOUG: It’s the same GAIN. And apparently, they’re unrelated to the GAIN that get advantage, which is from a hunting, hunting…

BEN: Oh, damn it. Does this mean Hedvig is more right than I was? That sucks.

DOUG: Well, this is going to… The paths are unexpected because this is one that has changed meaning. We have it as the awkward, clumsy ungainly. That’s a 17th century modification. In Middle English, it was more like unfit, improper. You’re physically improper when you’re ungainly, but it was a more general thing. And really the verb ungain… or not ungain, the form of the adjective ungain was inconvenient, disagreeable, troublesome. It’s something that is not gain. So, you have this G-E-I-N in Middle English, kind, helpful, reliable, beneficial. And that is one of the Viking words that got into English, it’s a gein.

HEDVIG: Oh, my god. I know it.

DOUG: Old Norse gagn, straight, direct, helpful, Proto-Germanic root. AGAIN is that word, gagn, with the prefix on it. So, it’s something towards. It’s something that is on toward is on-gagn.

HEDVIG: In German, it’s still gegen, for. If you are antivax, for example, you are gegen-vaccination

DOUG: Right, against. AGAINST and AGAIN are the same word.

DANIEL: Far out.

DOUG: They just differentiate.

DANIEL: That’s a good one.

DOUG: Yeah. And that’s why it has the hard G. That’s the Norse. That was a sign, the Germanic.

DANIEL: Good job, you two.

HEDVIG: So pleased.

BEN: I’m going to think that I would just like to remind Hedvig that I am on two points and that she is one.

HEDVIG: Thank you, Ben.

DANIEL: You’re not supposed to…

HEDVIG: I’m also keeping track.

DOUG: He’s shooting the moon.

DANIEL: And then, there’s this one from Anne and Diego. Anne asks, this is for all three of you, “Why are we BEDRIDDEN when we are sick? All the other -RIDDEN suffixes seem to mean beset by, like guilt ridden or pest ridden.” Then, Diego chimed in on Discord. “And is this RIDDEN related to RIDDLED, as in riddled with bullets? In which case, I guess bedridden would be like full of bed, because you have to rest and can’t get out of bed.” So, here’s my question. I got three. RID like get rid of. RIDDEN, as in bedridden or guilt ridden. And RIDDLED with. RID, RIDDEN, and RIDDLED. Do you think any of these are related? And I’ll give you my guess first. I said that RIDDLE is the odd one out, but RID and RIDDEN are the related ones.

HEDVIG: Can I add the fourth one? Like, I have RIDDEN a horse.

DANIEL: Okay, well, let’s explore that then. Do you think that riding comes into this at all, Hedvig?

HEDVIG: Okay, yeah, I’m going to… I want all four in there because otherwise it feels empty. [BEN LAUGHS]

DANIEL: You can’t do four!

BEN: I created a conceptual linkage in my head and now if I don’t include it, everything’s wrong.

DANIEL: Everyone must now have this linkage.

HEDVIG: Yes.

DANIEL: Yes, Hedvig.

DOUG: If you go to six, everything’s related to everything else.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: All right, Doug… No, I’m going to ask Doug last, but, Ben, I’m going to you.

BEN: I reckon I’m going to be discordant with Daniel, which is always just a really winning strategy in this game.

DANIEL: Well, it has been so far. You’re doing a crackerjack job so far.

BEN: I think RIDDLED and RIDDEN, so BED RIDDLED and BEDRIDDEN — I know BED RIDDLE isn’t really a word, but like riddled with lice or whatever — I reckon they are related. I reckon they are a divergent thing that kind of was talking about a similar thing to be sort of under the unwanted impact of in some way. And I think RID and RIDDANCE are unrelated.

DANIEL: Oh, interesting.

BEN: So, there’s a fifth, Hedvig. Sorry, Hedvig, RIDDANCE.

HEDVIG: RIDDLE, like what Gollum does to Bilbo.

DANIEL: Yep. Okay, well, I’m going to keep it to the three, RID, RIDDEN, and RIDDLED. So, what do you think, Hedwig, out of those three?

HEDVIG: Yeah. I’m on the same path, I think, as Ben was, if I don’t mistake so that BEDRIDDEN and RIDDLED with fleas seem related and get rid of something seems different because both BEDRIDDEN and RIDDLED with is like something towards sort of, you are ridden with the bed, you’re ridden with fleas. Whereas GET RID OF is to remove something, and that seems very different. So, I think it’s A and C that are related. And then I think… I don’t know what to do about my horse riding and my riddles. I don’t know. I have no idea.

DANIEL: If you had to tie that to one, which would it be? Which one’s related to RIDE?

HEDVIG: I think BEDRIDDEN, I would tie to horse RIDDEN.

DANIEL: Interesting.

HEDVIG: I also think… Is there something with like nightmares? That’s like a person who rides you, right? And they’re nightmares?

BEN: Ah.

DANIEL: Maybe. Okay, well, we’ve got our answers. Doug, what you got? Do you know this one?

DOUG: I’m pretty sure that the RIDDLE that means filled with holes is from a different root and it’s related to the sieve words. Sieve words in Latin and Greek, pre-Roman and so forth. So, I’m going to write that one off. And the other two, they are related. And I had to look this up, I was pretty sure, with the sort of looks like a past participle adjective, but you somehow find it’s flipped from the sense you expect the verb to go in to be hagridden, to be priest ridden is to have them on you. But in bed, you’re on the bed. And there was a lot of that. This is an old belief that a nightmare is a hag rider. There was in Old English a noun.

HEDVIG: A woman.

DOUG: Okay, yeah, but even further back than that… That’s what I was thinking it was going to be. But even further back than that, in Old English, there is a noun, BEDRIDER, a guy who’s stuck in bed.

DANIEL: He’s riding that bed.

DOUG: There’s no verb, but from that they back-constructed or got an adjective. A bedrider is… That guy is bedridden, he’s got bedrider, you know. It’s not coming in the usual path, so it has a reversed sense from what…

BEN: Fascinating.

DOUG: …you’d expect. The other one is HAGRIDDEN comes from being ridden by a hag.

DANIEL: Yeah. That’s what they used to call sleep paralysis.

DOUG: Right, right.

DANIEL: When your brain was awake, but your body couldn’t move. So, the answer is RID, RIDDEN, and RIDDLED are all unrelated, but RIDDEN and RIDE are related.

DOUG: Yeah, the RIDDEN in RIDE is… It looks like the past participle of ride. It’s identical to it, but it’s not actually etymologically that, but it is.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: So, Hedvig pretty much got everything, everything, everything correct.

HEDVIG: No.

DANIEL: You didn’t?

HEDVIG: Because I said that BEDRIDDEN and RIDDLED with holes were related.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. She made the same mistake as me.

DOUG: Oh, okay.

HEDVIG: Teacher, teacher, I got it wrong!

DANIEL: Thank you for your honesty. And I’m so impressed that you managed to connect RIDE with RIDDEN, because I had not made that connection. Yes, a RIDDLE was a coarse sieve. And the notion of bullet RIDDLED meant making somebody look like a riddle. RIDDEN is from RIDE. A horse that has been ridden has also been broken in. And if you are guilt ridden, it’s been riding you. And then, RID is from a totally different word from ridan, something like to clear land.

HEDVIG: Wait, wait, wait. You just said that BULLET-RIDDEN makes you look like a riddle. You said that as if that was a normal sentence.

BEN: Because before that, he said a RIDDLE is like a sieve. Like, it’s a different word for SIEVE.

DANIEL: A colander.

HEDVIG: Oh, I blocked that out because I always struggle with SIEVE /sɪv/.

DANIEL: Oh, right. Because it doesn’t look right. Should be sieve /siːv/.

HEDVIG: It doesn’t look right.

DANIEL: Sieve /siːv/.

HEDVIG: Colander.

BEN: A pasta strainer.

DANIEL: I like to put a colander on my head and say “I’m under a terrific strain.”

BEN: Oh no.

DANIEL: Dad joke!

DOUG: Dad joke.

DANIEL: Thank you to everybody who’s been giving us these Related or Nots. And thanks, Doug, for your expertise. That was a lot of fun and I enjoyed playing that with you. And who better to play it with than Douglas Harper of Etymonline.

BEN: Literally, no one. Literally, no one better to play it with.

DANIEL: There’s… there’s not anybody.

DANIEL: Shall we get to a question more or two? Because there are some etymological things going on.

BEN: Yes, please.

DANIEL: This one’s from Allister via email, hello@becauselanguage.com. “Hi, Daniel. Love your show. Thank you. Could you please produce it more often?” [LAUGHS]

BEN: Daniel, you’re not allowed to write things into people’s questions. That’s not okay.

DANIEL: It’s a Dorothy Dixer. Yeah, that’s it. Okay, this one’s going to take us to some strange places. “I need your linguistic help please,” says Allister. “I have been contemplating Charon…”

BEN: The ferryman of Greek mythology.

HEDVIG: The river Styx.

BEN: Yeah, who would take dead souls to Hades, I believe.

DANIEL: That’s the one. He says, “I have been contemplating Charon… without fixing a price.”

HEDVIG: Wait, wait. Sorry. Is this person saying that they’ve considered dying? I don’t understand how you contemplate Charon.

DOUG: Right.

DANIEL: It’s okay to just think about Charon. That’s not necessarily a worrying sign.

BEN: I think about…

HEDVIG: Okay.

BEN: This is like the Roman Empire thing. Sometimes, you just think about random bits of Greek mythology.

DANIEL: And I love a good de Burgian reference. And that’s obviously from Chris de Burx. Anyway, when you cross his river, it is described as Stygian.

BEN: Oh! not Styxian.

DANIEL: Not Styxian. “Are there any other examples where the adjectival X becomes a G? Should we not describe cyclists as LATEGIAN or Keanu Reeves fans as MATRYGIAN? Or this alteration as SUFFIGIAN? Many thanks, Allister.”

BEN: I don’t know if people listening to this will understand that each of those words if you back trace it and put an X where the G is are, respectively: latex, matrix, and suffix.

DANIEL: Thank you, Ben.

HEDVIG: Right.

DOUG: Yay.

HEDVIG: Also, because I live in a place where most cyclists are not the latex kind.

BEN: But you did live in Australia. And not only that, you lived in Canberra, so you…

HEDVIG: I’ve seen it. And they terrified me.

DANIEL: I’m sorry.

HEDVIG: Because they come up behind you and they say, “On your left!” And I’m like, “Fuck, who’s talking to me? I’m biking to work. Fuck off.” Anyway, cyclists who wear latex could be latexians and letigians, Keanu Reeves fans — Keanu Reeves starred in Matrix — could be matrixians or matrigians. And all of these things are suffixes, so are they suffigian or suffixal?

DANIEL: Yes.

HEDVIG: So, why does the X turn to a G in some places and not others is the question.

DANIEL: Okay, well, Doug, help us out here.

DOUG: Eh, you’re on your own. No, this is Greek grammar. I tried to think of other examples, I couldn’t, but I’m trying to reach for my Greek lexicon without unplugging the mic.

BEN: I think I can think of a reverse-ish version of this, maybe.

DOUG: I know they’re out there. I just can’t think of one.

BEN: The only one I can think of is if you are someone’s patron, you are giving them patronage, but you can be described as patrician.

DANIEL: That’s interesting.

HEDVIG: That’s Latin, but yes.

DOUG: I’m looking at… In the Greek though, they have words that end in X. And I’m trying to figure out how you would do the related… The form of that. And this is going to be one of the things that Latin did to Greek, like how Odysseus comes out Ulysses. It screws Greek up badly. Latin treats Greek the way French treats Latin. [BEN LAUGHS]

DANIEL: Okay, well, I remember from my schoolboy Latin that REG was this underlying form for KING. And if it was just in its normal nominative form, then it was rex, but reg-is, and that’s why we get REGAL. And I remember that we had a thing about law being LEX, the word turning into LEGAL. There was also a legal/loyal thing going on.

BEN: Okay, there’s a little bit of precedent here, X to G.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: We should also point out maybe that the X is sort of two sounds in one, right? There’s a /k/ and a /s/ sound. And the /k/ sound is actually produced in the same place in the mouth as the /g/ sound.

DANIEL: That’s it.

HEDVIG: So, they’re very close to each other. The only difference between them is whether your vocal folds are vibrating at the same time or not. So, you can often see switches between sounds that are in the same place in the mouth. So, this is the same as /t/ and /d/, and /f/ and /v/, they can often flip between each other, depending on its context. So, the sound that comes after /k/ in REX is an S, which is also what’s called unvoiced, so your vocal folds are not vibrating. Maybe if that gets flipped so you have something else like you said you wanted to put /l/, so rexall, maybe what happens then is that the /a/ because that’s voiced maybe makes the /k/ voiced.

DANIEL: It’s a little simpler. What’s happening is the underlying form is REG-, and if you put an S on it like you’re supposed to for a nominative singular, it becomes REGS, which sounds like REX, close enough. And then, you can take the REG and you can do other things with it in different forms: regis, regal, and so on.

DOUG: Hey, I finally got a hold of Liddle and Scott, and actually the adjectival form in Greek is Stygios. It does have a G.

DANIEL: Yeah, there we go.

HEDVIG: So, it’s the other way around. So, it’s the S that is making the /g/ sound.

BEN: Yeah, the X’s are the… yeah.

DOUG: They actually put a noun, and they drop that probably for the sound things you were describing. It would have been more euphonious to do that. Yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: The /g/ is assimilating to the /s/ and becoming unvoiced /k/, for you linguists who know what that is.

BEN: So, for the benefit of our listeners, really quickly, to answer the question for Allister, we’ve got the wrong idea, and it was never the River Styx. It was the River Stigs, probably. And then, people got sick of being like, “Well, that’s dumb, because that sounds bad. Let’s just call it the River Styx with an X.” And so, the X versions are just people probably starting out by going G, S and then being like…

DANIEL: Chaos.

BEN: “Total waste of time…

HEDVIG: Yeah, something like that.

BEN: …What are we doing here, folks?” And then, it’s just a bunch of X’s came about.

DANIEL: You got it. Okay, last one from PharaohKatt. “So, I have been wondering a thing. I learned that the Auslan word for WHY and BECAUSE are the same.”

BEN: Whoa.

DANIEL: “With a slight variation.” WHY? BECAUSE… blah.

BEN: [LAUGHS] That could make for some really good teenage sign. Why? Because.

DANIEL: Because, yeah. You get the sign WHY and you just hand it right back.

BEN: [LAUGHS] I don’t know if that’s the high school teacher in me feeling it real hard, but that’s what it read to me.

DANIEL: Why? Why! “Well, this is also true for spoken Spanish. ¿Porque? Porque… And I suspect other Romance languages as well. Are there other languages in non-Romance families where why and because are the same or almost the same? And why does that happen?” Does anyone want to try this one? Because I did a little bit of work on this.

HEDVIG: I think there are other languages where that’s the case, and I think that… So, in Swedish, you can say that it’s why is varför, and because is därför. So, it’s actually WHERE and THERE. WHEREFORE and THEREFORE, which you actually get in Old English, if I’m not mistaken, as well. Therefore, we should plant seeds, whatever.

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

HEDVIG: But the thing that’s good to think about with things like this is if they’re doing a similar job, but they occur in very different contexts, so why will always be in questions at the beginning, and because will not be at the beginning in questions. So, you can afford to have them be similar because you have enough other things around to tell you which one it is. So, my suspicion is… I don’t know. I think there are some other languages that do this, but it’s kind of a cheap way to do things because you have enough stuff around you probably to tell you which one it is.

DANIEL: Yeah. I took a look at a translation page on the web which had like 100 different languages, how they say why and how they say because, just to see if lots of them were the same. Lots of them were the same and I was kind of limited to ones in writing systems that I could parse. Like, in Aymara, the word for both of them is Kunata. In Chichewa, the word for both is chifukwa. There are lots of languages, like there are about 12, where it’s pretty much the same word. And it makes sense that it would be the same word, because what you’re doing is you’re saying, “Reason: what? Reason: that.”

BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: So, there’s not tons of languages, but there are quite a few, and I think we’ve uncovered why they would be the same. They happen in close proximity to each other. They’re interlocking pairs, and they’re just two different halves of the same question.